Everything you need to know about this week's comet

Considered a long-period comet, Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, AKA Comet Purple Mountain-ATLAS, AKA Comet C/2023 A3 recently made its closest approach to the sun, after having traveled to the inner solar system from the Oort Cloud. It’s forecasted to be brightest tonight around magnitude -3, and around magnitude +2 on Oct. 12 when the comet is at its closest point to Earth.

Comets are leftovers from the formation of our solar system, originating in distant reaches far enough from the sun where it was cold enough for ice to exist. Fun fact: “Comet” comes from the Latin “cometes,” which in turn comes from the Greek “kometes,” meaning “long-haired.” This all in turn comes from Aristotle using a derivation of the Greek “koun,” “kountng” (“stars with hair”), which eventually came to be “kometes” (long-haired) and then “cometes,” in Latin, and finally “comet” in English.

As comets get closer to the sun, the sun’s light and heat causes ice in a comet’s nucleus to turn directly from a solid to a gas, creating a “coma.” As this temporary cloud of material is blown away from the nucleus by the sun’s light and by the solar wind, multiple comet tails and trails can form. Remember comet Hale-Bopp.

Comets get the designation long-period if their orbits are more than 200 years long; C/2023 A3’s orbit is at least 80,000 years long. It most likely came from a region called the Oort Cloud, which is a spherical volume surrounding the visible portion of our solar system that may have formed early on in our solar system’s history. It is thought that these icy objects were flung outward away from the sun due to the gravitational action of the planets. The Oort Cloud has only been theoretically predicted — we’ve never seen Oort Cloud objects out at their vast distances due to their tiny sizes, cold temperatures and dark color.

The length of its orbital period, how fast it is traveling and the angle of its orbit all point to C/2023 A3 being an Oort Cloud comet. At some point in the more recent past, something gravitationally jostled C/2023 A3 (such as the gravitational tug of a passing star) causing it to exit the Oort Cloud, and it started to make its way toward the inner region of our solar system!

So, will this comet be visible from Earth again in 80,000 years? Not necessarily. It depends on how fast the comet speeds away from us after encountering the planets and the sun. If the comet’s speed is not fast enough to escape the sun’s gravity, it could theoretically visit us again in the distant future. However, if it is given enough of a kick in speed by the gravity of other objects, its orbit could become hyperbolic. This means that it might eventually escape the gravitational pull of the sun. For comets in extremely elliptical orbits, it doesn’t take much of an influence to have their orbits perturbed by gravity to either slow them down or speed them up. A comet’s first visit here might be its last!

So how bright will this comet get? That, unfortunately, is one of the hardest questions to answer about comets. No two comets are exactly the same, and we don’t know for sure what a comet is going to do until the sun’s light and heat interact with it.

One thing to note about comet brightness is that the comet will not be uniformly bright all along its entire length. The end of the tail will usually be fainter than the head, so therefore the head of the comet will likely be the part of the comet that is easiest to see. The full extent of the comet’s tail will probably show up better in photographs.

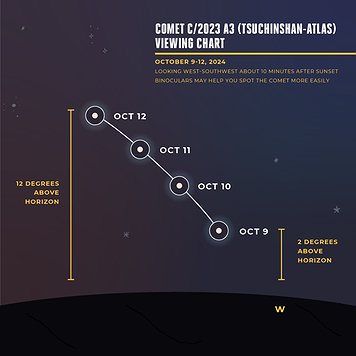

One potentially very interesting date for this comet is tonight. Right at the time of sunset, the comet will be very, very low to the horizon — only a few degrees up. The low angle between the comet and the sun means that sunlight scattered by dust from the comet might temporarily bump up the comet’s brightness significantly, possibly to around magnitude -2.5, which is about as bright as Jupiter is in our night sky. However, because the comet will be extremely low to the horizon, looking through that much air plus being in so much sunset glare might counteract much of that visual brightness bump. It will only be above the horizon for about 15 minutes or so after sunset before it sets.

To be safe, just wait until the sun fully sets to try to find the comet tonight. Or, better yet, wait another day or two for the comet to be higher in the sky after sunset. It won’t be as bright as it might be tonight, but at least you won’t risk your vision as much trying to find it. The comet could be nearly as bright just after sunset Oct. 10-11.

Graphic credit: The Adler Planetarium

To get an idea of how far something is above the horizon: Make a fist, extend your arm all the way and put the bottom of your pinky on the horizon. The top of your index finger will be roughly 10 degrees above the horizon. Each finger of your fist represents two and a half degrees.

On Oct. 12-13, the comet will be around magnitude +2, possibly around magnitude +1. Magnitude +2 is about as bright as Polaris in our night sky. It will begin to dim after that date. The moon’s light may interfere a bit with the brightness of the comet around mid-October, as well. By the end of October, the comet will be a lot dimmer, probably around magnitude +6, which is at the human limit of naked-eye visibility under a very dark sky. Viewers in light polluted locations will need binoculars or a small telescope to see it then.

Binoculars should help you locate it, especially after Oct. 15, but do not start using binoculars to find it until the sun has fully set below the horizon. You will cause permanent damage to your eyes from accidentally viewing the sun directly. If you point an unfiltered telescope or pair of binoculars at the sun, eye damage from the burn will be instantaneous and eyesight loss will be permanent!

And if that weren’t enough, another comet was just discovered 10 days ago, C/2024 S1 (ATLAS), and it could reach as bright as magnitude -5 to -7 when it comes closest to the sun Oct. 28. It could be brighter than Venus, the brightest planet. The Southern Hemisphere will have the best view before perihelion, and the Northern Hemisphere could see it in the morning skies after its close encounter with the sun.

Remember, comet brightness is notoriously difficult to predict and they don't always live up to expectations. I, personally, have been disappointed many times.

• • •

Content of article adapted from: Michelle Nichols,: Everything You Need To Know About Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, AKA Comet Purple Mountain-ATLAS, AKA Comet C/2023 A3, theadlerplaneterium.org Oct. 7, 2024.

• • •

John Taylor is an amateur astronomer who lives in Hayden.