HUCKLEBERRIES: Football, she coached

Beverly Sullivan had no use for feminism 50 years ago when she stepped onto the McEuen football field.

She told the Coeur d’Alene Press bluntly: “Women don’t belong in football.”

But she felt she had no other option than to coach her son’s flag football team when the city parks and recreation program came up two coaches short.

Beverly, then a secretary for the old Harding School, was reluctant to cross the gender barrier. But she didn’t want the league to fold and disappoint her sixth-grade son and his friends.

“Where are all the men?” she wondered as she learned to distinguish a scrimmage line from a chow line. “That’s what these boys need in athletics. They don’t know what they are missing. I watched my son play football for the first time, and I’ve never had a better experience.”

At first, Beverly figured she’d coach until a man took over. And, after the first practice, one did enlist as an assistant: Robert G. Nelson, whom she credited for the team’s success. Her Lions Club won its division before losing in the league’s championship game.

“Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed every minute of my coaching experience,” Beverly told The Press after the season. “But I would have been cheating those boys if it hadn’t been for Bob Nelson.

But Beverly remained in charge and had no problem gaining her players’ respect. Most of them were friends of her son, Clint, and had been to her Fernan Hill home many times. She and her husband, LeRoy, had horses, motorcycles and other things that dazzle boys.

Beverly coached because LeRoy worked nights and couldn’t. But he patiently answered his wife’s many questions about football. In fall 1974, she talked and ate football.

Sure, she heard an occasional taunt from other coaches who told their players: “If you let a woman win, you’re really a crummy team.”

But Beverly had fun.

She didn’t plan to coach the following year when the boys moved up to tackle football.

Unless, of course, too few men volunteered to do so.

Misfire

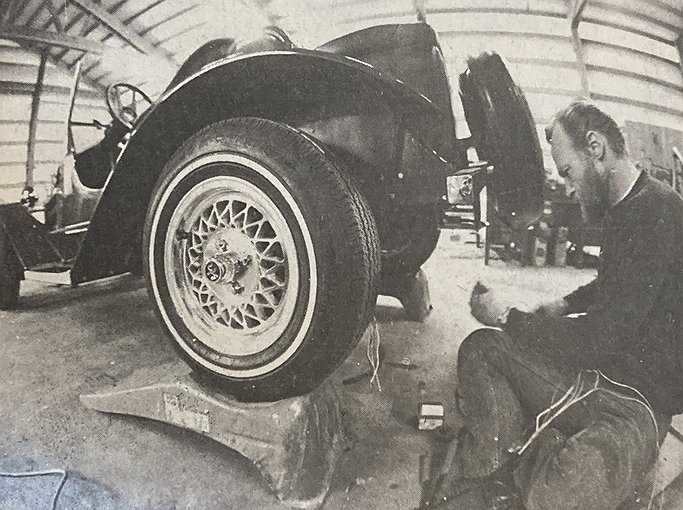

Post Falls isn’t the first city that comes to mind when you think of car manufacturers. Or unique automobiles.

But there was a time when a local man custom-made cars from the ground up.

From 1975-77, Don Stinebaugh of Post Falls and sons Leonard and Kenneth built — and estimates vary — from 97 to 119 Leata Cabaleros. They hand-made all the parts except for the engine and drive train.

But Stinebaugh, an inventor with at least 48 patents, including a quality snowmobile engine, couldn’t find a sustaining market for his Leata.

Critics panned his cars, which were modeled after Chevy Chevettes and named for Stinebaugh’s wife. Even four decades later, fault-finders chirped. In 2016, Brendan McAleer of The Drive magazine declared the Leata to be “the worst automobile in America.”

Doug Clark of The Spokesman-Review used McAleer's quote in a 2016 column, plus a description from Mitch Silver of Spokane's Silver (collector car) Auctions. The Leata Cabalero, Silver said, had the “squashed look” of an “old World War II German army helmet.”

After three years, Stinebaugh shut his operation only to resurrect it in 1979.

With but vague mention of the Leatas, Stinebaugh told The Press about his new models: the Stinebaugh I and Stinebaugh II.

His crew of 12 designed, engineered, upholstered, painted and manufactured its parts.

Stinebaugh said he hoped to build 200 to 250 roadsters annually. Although pricey, Stinebaugh said, they were “very reasonable for a hand-built car.”

Seems both Stinebaugh models went the way of the dodo, too.

“I should never have got into it,” Stinebaugh, then 72, admitted to columnist Clark in 1989. “I lost a lot of money.

Yet, he dared to act on a dream. And that’s more than most do.

O pioneer

Matthew Hayden’s grave is right where author Susan Snyder Lee said it would be — under a tall white monument in the southeast corner of St. Thomas Cemetery at the end of Sherman Avenue.

Hayden was the pioneer who won the right to name Hayden Lake in a poker game with neighbor John Hager.

But he was more than that, according to Lee’s book: “Mathew Hayden: A Man with a Fast Horse.”

In 1847, he escaped his native Ireland and poverty during the potato famine by migrating to the U.S. He was 15 years old, 5-foot-5 and rail thin, with dark curly hair and dimples, according to Lee. He earned his ocean passage by indenturing himself for five years as a New York farm apprentice.

Then, he joined the U.S. Army dragoons and soldiered his way across the country.

Later, he became an important property owner in Colville, Hayden Lake and Mission City (Cataldo).

He befriended Jesuits, Coeur d’Alene Indians and the area’s who’s who.

Ignace Hayden Garry, his grandson, became the last chief of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, according to author Lee.

On Nov. 28, 1890, Hayden died at age 58. Graves of his six children and other relatives surround his final resting place.

Huckleberries

• Poet’s Corner: Whether skies are/blue or murky/won’t much matter/to the turkey — The Bard of Sherman Avenue (“Thanksgiving Day Forecast”).

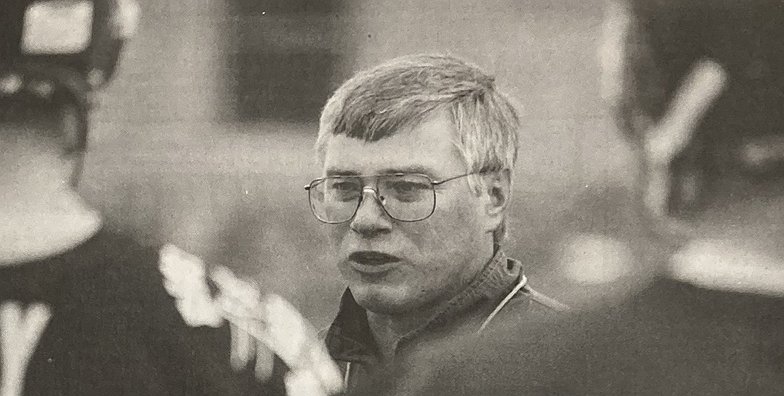

• A Slow Start: And the answer is — five years. The question? How long did it take Lake City, under Coach Van Troxel, to go from winless to a state football title game? LCHS footballers were 0-9 in the school’s first year: 1994. Then, they went 1-8, 3-6, 8-2 and 8-3. In 1999, the T-Wolves were 11-0 before falling to Vallivue 44-7 in the A-1 Division II championship game.

• Did You Know That … Seiter Hall, the 50-year-old former science building at North Idaho College, was named after Ed Seiter of Post Falls? And that it may be haunted? NIC honored the former trustee for helping to win funding for the college. The ghost, possibly of a Fort Sherman soldier, took a hiatus in 2005 when the science people moved out. But is believed to have returned in 2010 after an overhaul of Seiter Hall. That or the building was settling.

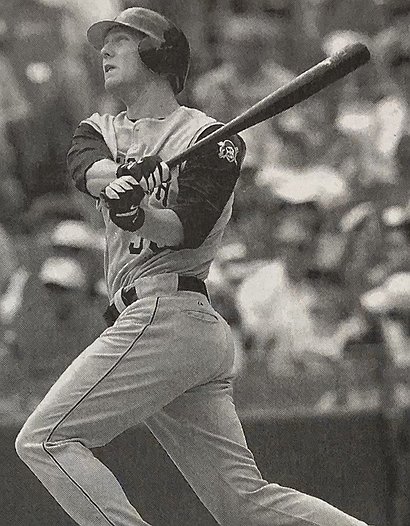

• Good As Gold: In November 2005, stoic Jason Bay almost cried after signing a four-year, $18.25 million contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was set financially. In 2004, he’d been the National League rookie of the year, hitting .282 with 26 home runs and 82 runs batted in. In 2005, he had another strong season and made his first All-Star team. Not bad for a former player of the defunct North Idaho College baseball team.

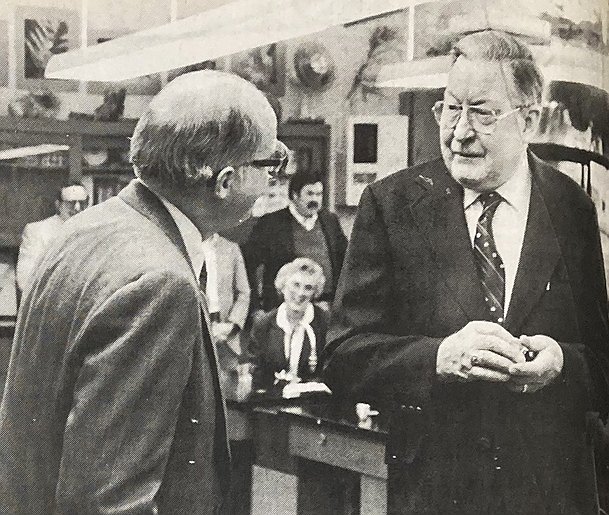

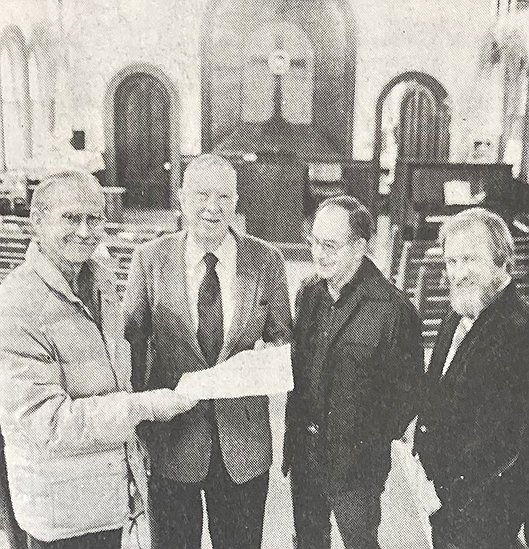

• In Good Hands: On Nov. 21, 1984, the Athletic Round Table handed ownership of the Fort Sherman Chapel to the Museum of North Idaho. In the late 1940s, ART, an organization of the town’s movers and shakers, saved the historic chapel from possible destruction when rumors swirled that a developer wanted to raze the building.

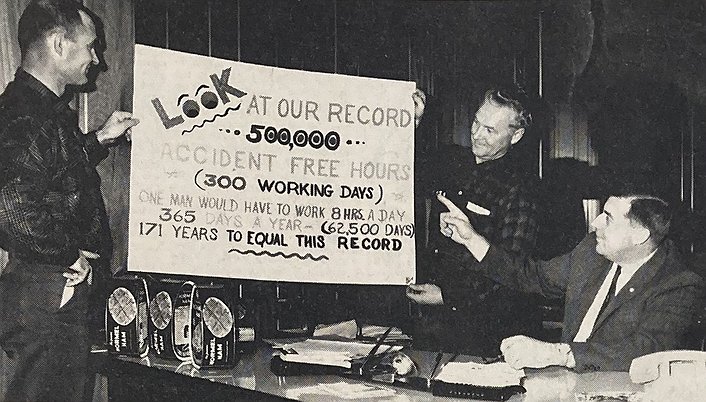

• Safety First: In the hazardous timber industry, Potlatch’s Rutledge Mill on the east end of town (now The Coeur d'Alene Resort golf course) set a remarkable record 60 years ago. The workers had gone more than 300 days and 500,000 hours without a lost work accident. The only Potlatch mill to top that mark was Lewiston’s — in 1938. As the 1964 Thanksgiving approached, management was thankful.

Parting shot

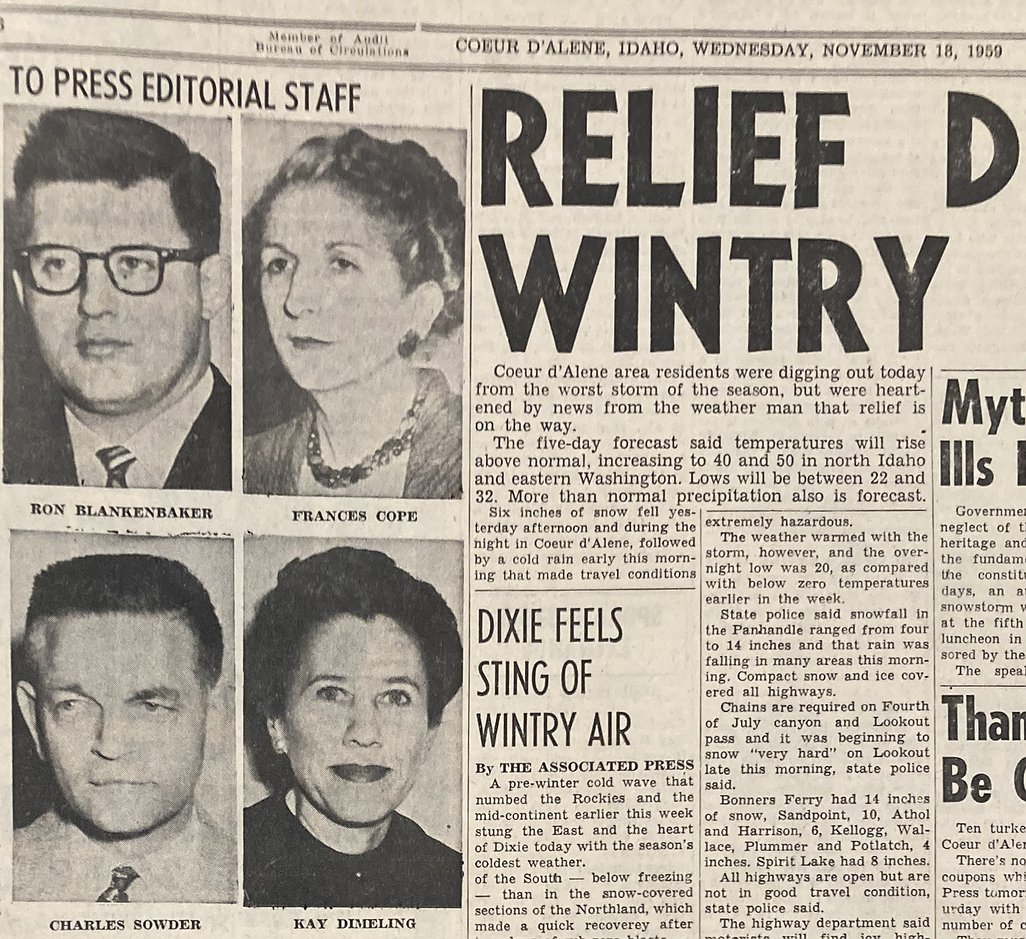

In November 1959, The Press showed its faith in the community and future population growth by almost doubling its editorial staff. Well, the result was humbler than it sounds. In a front-page story, news editor R.J. Bruning announced the hiring of two additional staff members to expand the newsroom from three to five. Kay Dimeling was to be the women’s editor. And Ron Blankenbaker was hired to fill the new position of sports editor. They joined veteran journalists Frances Cope and Charles Sowder. The future of North Idaho had never looked brighter, Bruning said Nov. 18, 1959. Freeways and highways were coming. And the rotary dial telephone had arrived. The staffers of 65 years ago are gone. But the paper is still here despite the unique challenges of 21st-century journalism. And the community? It is still thriving. Maybe too much.

• • •

D.F. (Dave) Oliveria can be contacted at dfo@cdapress.com.