HUCKLEBERRIES: Writer on trail of three missing women

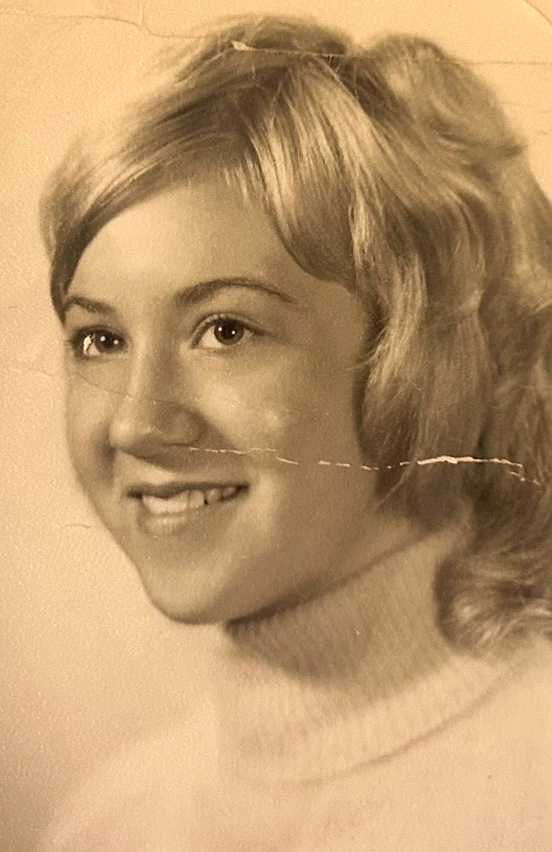

For almost 40 years, we’ve been haunted by a black-and-white photo of Deborah Jean Swanson, a Sorensen Elementary teacher who vanished from the area around Tubbs Hill.

Possibly caught off guard, the curly-blond, green-eyed instructor looks fully into the camera, mouth slightly open, as if surprised and uncomfortable to be the object of attention.

The media has published the picture regularly through the years as the anniversary date of Debbie’s disappearance came and went: March 29, 1986. And after all these decades? Nothing.

Debbie remains missing. So does Sally Stone (Reis), an exotic dancer at the old Kon Tiki Bar in State Line, who vanished seven weeks later. So does Julie Weflen, an operator for the Bonneville Power Administration, who vanished from a substation, northwest of Spokane, on Sept. 16, 1987.

Some believe the cases are connected. There were suspects. Some wrote about the women, including true-crime author Ann Rule, who devoted a chapter to Debbie Swanson in her book, “Kiss Me, Kill Me.” Others, including retired detectives and BPA officials, kept the cold cases alive.

Now it’s Doug Eastwood’s turn.

“People don’t disappear without a trace,” said the former Coeur d’Alene parks director. “Someone saw or knows what happened. I want to jog some memories.”

Doug has written two books: A history of the North Idaho Centennial Trail, which he helped build, and one about the March 1964 murders of his aunt and cousin in Las Vegas, “Closure Can Be a Myth.”

After he finished the second book, his publishing company, Bitterroot Mountain, asked Doug to write about the mysterious mid-1980s disappearances of the three Inland Northwest women.

Doug will tell readers who these women were and the effort that went into finding them.

Debbie was 31 when her car was located at the old Third Street lot with her purse and packages inside. One of 11 children born to a Minnesota couple, she was athletic, musical, a member of her high school cheering squad, gymnastics team, honor society and student council.

“She was always on the move,” Doug said.

Her parents were music teachers. And she and her sisters formed an accordion group.

Sally Stone, who disappeared at age 21, was adopted, left home early, and was later kidnapped. Doug describes her as a woman who never caught a break. She disappeared on May 16, 1986, after undergoing physical therapy for an injury that kept her from performing.

Julie Weflen’s disappearance received national attention as the result of her husband’s desperate search for her, according to The Spokesman-Review. Her photo appeared on dozens of billboards in four states and hundreds of thousands of posters after the Deer Park woman went missing at age 28. A $25,000 reward for information from the BPA went unclaimed.

Doug has visited the site of Julie’s abduction and is researching a possible tie to Debbie’s case.

Doug can be contacted at rdeastwood8687@gmail.com or at rd_eastwood via Instagram.

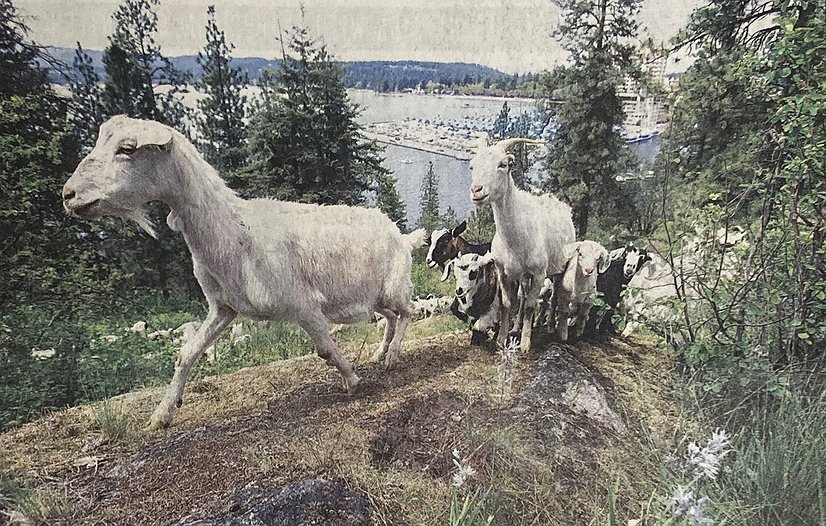

Got his goats

Goats once roamed Tubbs Hill — and not too long ago at that. We’re not talking “GOATs,” as in Greatest of All Time athletes like quarterback Tom Brady. But the kind that bleats.

For three weeks in the late spring of 2014, 200 goats from the Healing Hooves outfit in Edwall, Wash., wandered a portable, 1-acre enclosure on our hallowed hill, “consuming in a frenzy” pine needles, twigs, grasses, bark and leaves.

The four-legged mowers munched about an acre per day — and were on the clock for 22 days.

The city wanted to remove ground-level fuel to prevent fire from reaching the treetops. And the goats proved more economical than human crews. The goats cost $500 per acre chewed; the humans $900 to $1,500.

Said Katie Kosanke, the city’s urban forestry coordinator: “We just thought: ‘Why not give it a try?’”

A Press reporter noticed a few goats standing on their back legs in vain to reach a pair of men’s blue boxer shorts dangling from a leafless branch near their pen. But owner Craig Madsen wasn’t worried: “They won’t eat the underwear; they might mouth it.”

Even goats have limits.

Quite the figure

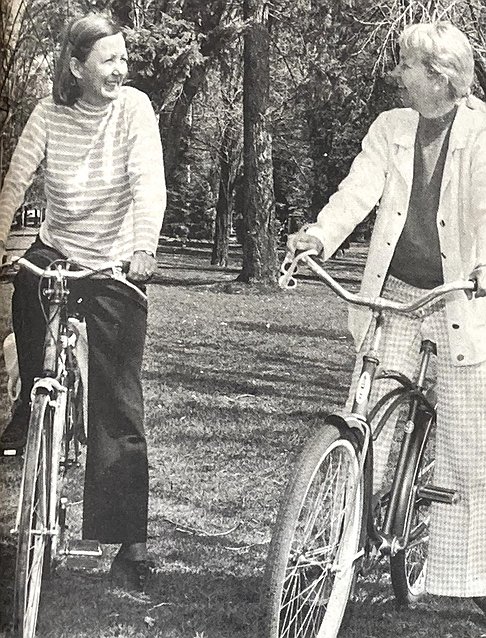

Mary Lou Reed, the Grand Dame of the Kootenai County Democrats, and her Fernan neighbor, Donna Young, were part of the local bicycle craze 50 years ago (May 28, 1974).

The two routinely rode their two-wheelers from their homes on the east end of Sherman Avenue into town to run errands and to beat postage increases by delivering their mail in person.

The national craze had become such an “in” thing in Coeur d’Alene that merchants couldn’t keep bicycles in stock. Carter Crimp of Dingle’s said he sold every 10-speed bike he could get his hands on — and that older people were buying them, too.

Some said the bike fad of the early '70s was fueled by the environmental movement. And the aforementioned Mary Lou and her late husband, Scott, certainly were conservationists. But Mary Lou had other reasons for pedaling her bike.

She told The Press: “We think exercise is marvelous for the figure and for keeping in shape. Plus, it’s more economical than driving cars.” Still is.

Huckleberries

• Poet’s Corner: The votes are cast/the count complete/please take your signs/now off our street — The Bard of Sherman Avenue (“Request for the Candidates”).

• Do Over: The state of Idaho exhibit for Expo ’74 in Spokane was so poorly done that Gov. Cecil Andrus ordered designers to overhaul it. A Press story of May 16, 1974, didn’t say why the exhibit tanked but reported that the public response was “emphatically and overwhelmingly negative.” A metal sculpture of an underground miner from the Silver Valley was taken from the State House rotunda to be displayed prominently in the upgraded Idaho exhibit.

• New Beginning: After surviving a recall attempt, former three-term mayor Sandi Bloem enjoyed a last laugh when she helped dedicate the refurbished McEuen Park on May 24, 2014.

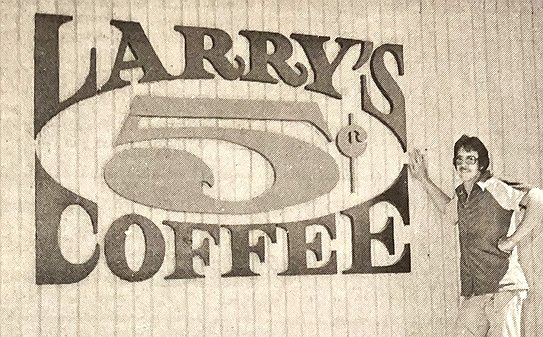

• Loss Leader: The late Larry Anderson of the old Larry’s 5 Cent Coffee on Government Way had a good reason for pouring java at below cost back in the late ‘70s. Get them in the door, he figured, and they would buy other delicious dishes on his menu. It worked, too. Later, he and wife Pauline ran Franklin Hoagies for 23 years and enjoyed continued success.

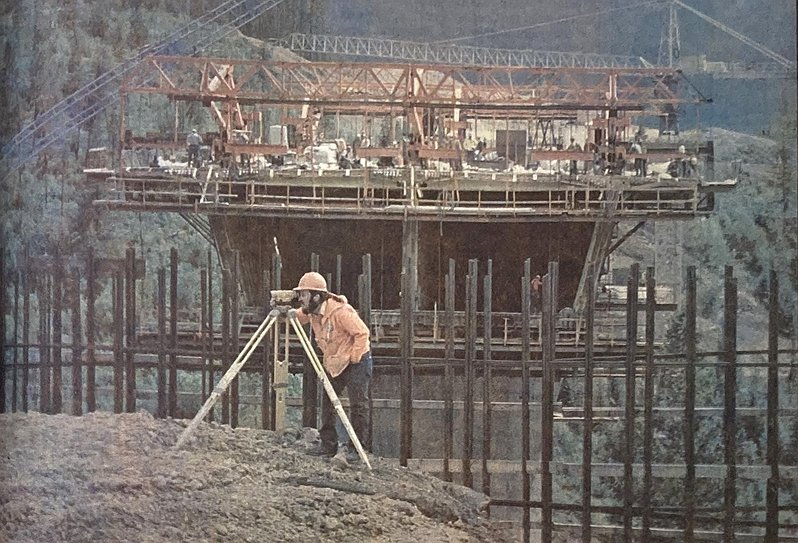

• Cruising Along: Thirty-five years ago (May 21, 1989), construction on the 1,730-foot, $15.7 million bridge over Bennett Bay (Memorial Bridge) was six weeks ahead of schedule for a spring 1991 opening — and only $281,000 over budget. Contractors credited good weather for staying on track. Said one: “It’s kind of like hay when the sun shines.”

Parting shot

The late Rod Jessick, executive chef of The Coeur d’Alene Resort for more than 37 years, began his career by jamming his mother’s blender with a rubber spatula. To pay for the broken appliance, he washed dishes at the old Pagoda Restaurant in Post Falls. And he quickly excelled around a stove and felt at home in the kitchen. All this according to a Press profile story on Rod 30 years ago (May 25, 1994). And there’s more. He received no formal culinary training (although he urged others considering a career in cooking to get some schooling). Rod told The Press that he learned to cook through hands-on training from some of the best cooks around, including his mother, whom he described as “the best cook I know.” It’s not how you begin that counts, it’s how you end up.

• • •

D.F. (Dave) Oliveria can be contacted at dfo@cdapress.com.