Almost Home: North Idaho families face barriers to permanent housing

COEUR d’ALENE — Like many people, Heather Bischof moved here and got a job. But she soon found she wasn't making enough money.

“I was very unaware of the wages, $3 and something cents an hour,” Bischof said. “I’m like, ‘How, especially in dead season, am I supposed to make enough tips plus paycheck to afford my rent?’”

Bischof and her roommate fell behind on rent and soon found an eviction notice on their door. For Bischof, homelessness was about to become a reality.

In Idaho, 1,611 homeless individuals were counted in early 2023, but Katherine Hoyer with Panhandle Health District said that number can be deceiving.

It follows the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's definition of homelessness: having a “primary nighttime residence that is a public or private place not meant for human habitation."

Advocates say that doesn’t match the reality many people face. Families may not qualify as homeless even though their situation is precarious.

“When you have a child, you will do anything it takes not to be in that situation,” said Lisa Donaldson, a case manager for Family Promise of North Idaho. “Maybe you’re in your car and your kids are at your mom’s, or you’re getting a hotel any time that you can, or you’re staying with a friend and then another friend.”

Chris Green, director of the Heritage Health Street Medicine Community Outreach Program, knows this from seeing many North Idahoans go through it.

He said that most people who lose their housing for the first time don’t initially think of themselves as homeless because they don’t identify with the stereotypical image of a person on a street corner, clutching a sign and asking for money. But as time goes on, mindsets shift.

“When the streets are cold and the people in your town are cold and turn a blind eye, you start to identify as a homeless person,” he said.

When someone becomes homeless, Green said, it’s critical to connect that person with resources and services as early as possible.

“If someone is, within 90 days, able to get housed and get back on their feet, they rarely become homeless again,” he said.

But the longer someone spends without housing, the harder it is to return to normal life. About one-third of people who are homeless for six months will become chronically homeless, Green said. Only about 10% of people who are homeless for longer than a year will go on to gain permanent housing.

It's difficult to track the exact number of people who need housing but don't meet the HUD definition of homeless, but their numbers appear to be increasing.

Nathan Whatcott is the homeless liaison for Kellogg School District. He said he noticed an alarming increase in the number of families staying in campers and RVs.

“Our current store of housing is not great. There’s just not a lot out there,” Whatcott said.

And what is available is getting more expensive.

“The rents are so high here, including the first and last month's rent," said Barbara Miller, founder of the Silver Valley Community Resource Center.

Fortunately, people and organizations are stepping up to help.

That's how Bischof managed to stay housed.

“I was to the point where every single day I was shaking because I was so stressed out and my stomach just felt like it was empty and in knots,” Bischof said. “I tried looking into any resources I could.”

Her supervisor at a local brew pub contacted CDAIDE, a nonprofit that helps hospitality workers in crisis. They helped her with two months of rent and fixed her car.

“CDAIDE has been a blessing,” Bischof said. "Even though it couldn't cover everything, I didn’t expect anything. I was so thankful. I was in shock for quite some time."

Family Promise also aims to help families avoid homelessness in the first place, whether by rental assistance when funding is available or by other means.

“We can help them come up with ideas of how not to come into the shelter and avoid that trauma for their children but still be able to work with them and help them while they’re staying somewhere else,” Donaldson said.

Family Promise partners with 18 local churches to provide homeless families with a safe place to stay and receive services while they find permanent housing. During the day, parents and children can spend time at a shelter. At night, churches open their doors to the families.

The organization also provides supportive services, including classes on parenting, financial literacy, being a good tenant and more. Even when a family “graduates” by entering permanent housing, services remain available to them.

“We can walk with a family for as long as it takes them, usually up to a year, to walk on their own,” Donaldson said.

Even school districts can help. Whatcott said the district can sometimes use federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act funds to get propane so families can cook and stay warm, but it can’t assist with rent.

But not everyone who needs assistance will ask for it.

When people need help, Green said, shame can stop them.

“Be brave,” he said. “Wade into the discomfort. Ask for help often and everywhere. Realize that there are people who care and people who want to help and don’t let a bad experience turn you away from asking for help.”

Green invites anyone facing homelessness to visit the Heritage Health Street Medicine Community Outreach Center at 109 E. Harrison Ave. in Coeur d’Alene.

He said that perhaps the biggest misconception he encounters about Kootenai County’s homeless population is that it’s made up of “outsiders.”

“Over 95 out of 100 are from North Idaho,” he said. “The vast majority of people we serve are born and raised here. They have nowhere else to go.”

Last week, the sun beat down on Bischof's front porch as her son, Austin, 7, and daughter, Ellie, played in the water during the heat of a summerlike May evening.

Bischof paused as Ellie came up the porch step with a purple pansy in her hand, asking if her mom to please put it in her hair. Ellie, who would turn 5 the next day, held still and grinned as her mom smoothed her flyaway strands, tucked the flower behind her ear and kissed her on the top of her head.

The downtown Coeur d'Alene home is well-lit. Down the hallway past the bedrooms and the laundry room, a door opens to a small fenced backyard where grape vines grow along the fences and a patch of rhubarb is already exploding with life on the other side of the wood.

“This feels so good,” Bischof said. “We’re really lucky to get in here. I love it so much."

She stood on the back porch of the home, which she rents with a new love interest, Sean. Their rent is $2,000 a month. It takes up a lot of their income, so they budget carefully.

Bischof looked around the backyard, sharing how this was the first time she hadn’t felt the impending doom of having to find another place to live.

“This feels like home,” she said. “I’ve never felt like I could settle down and call something home. I know I’m not going to have to struggle and scramble to find a place to live for us in a month from now or two months from now.”

Heather Bischof places a flower behind her daughter Ellie's ear May 9 as they enjoy the sunshine on the front porch.

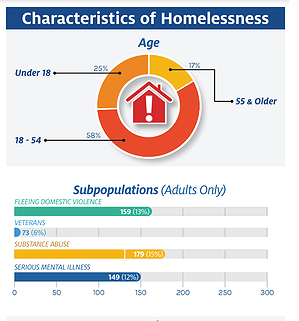

Heather Bischof places a flower behind her daughter Ellie's ear May 9 as they enjoy the sunshine on the front porch. In the 2023 point in time survey of homelessness coordinated by Idaho Housing and Finance Association (except Ada County), 58% of homeless individuals are 18-54 years old, 25% are under the age of 18 and 17% are 55 or older. The same survey found that 15% were homeless due to issues related to substance abuse, 13% were fleeing domestic violence, 12% had become homeless due to issues related to serious mental illness and six percent are veterans.

In the 2023 point in time survey of homelessness coordinated by Idaho Housing and Finance Association (except Ada County), 58% of homeless individuals are 18-54 years old, 25% are under the age of 18 and 17% are 55 or older. The same survey found that 15% were homeless due to issues related to substance abuse, 13% were fleeing domestic violence, 12% had become homeless due to issues related to serious mental illness and six percent are veterans. In a point in time survey coordinated by the Idaho Housing and Finance Association across the state (excluding Ada County), 1,611 homeless individuals were counted January 25, 2023. This number is approaching the numbers noted in 2020. (The survey did include a note that the pandemic limited the scope of the survey in 2021 and 2022.)

In a point in time survey coordinated by the Idaho Housing and Finance Association across the state (excluding Ada County), 1,611 homeless individuals were counted January 25, 2023. This number is approaching the numbers noted in 2020. (The survey did include a note that the pandemic limited the scope of the survey in 2021 and 2022.)