When libraries weren’t free

In this American culture war over books, Ground Zero is the public library.

It’s interesting, to say the least, watching from the sidelines as free access to information shrinks. Especially considering that for more than 300 years, it kept expanding.

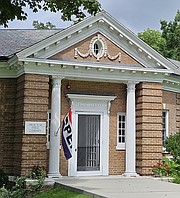

About a year ago Mr. Patrick and I enjoyed an autumn road trip through New England. Beyond changing leaves and an endless stream of charming historical edifices, I noticed another difference from Western views. Most small towns and villages have a library. Literally housed in typically lovely, 18th or 19th century renovated homes; each has the same (quintessentially wooden) sign: “Free Library.”

Why “free,” I wondered? Libraries are free nationwide. Is the term a New England thing?

It’s an American history thing. Tax-supported libraries for everyone first appeared in the 1840s, but other kinds of libraries in the colonies predated those by more than 150 years. Very few were free and accessible to the public.

In early colonial times, other institutions dubbed “public libraries” had book collections held in common (not by one individual), often donated by wealthy patrons or established by donation. These were sometimes part of a college, such as Rev. John Harvard’s literary legacy to New College, which became Harvard University. Other libraries were in members-only clubs, or for exclusive use by a professional guild or other private group. The books in those libraries were accessible only to those the institution served, or who paid some kind of subscription fee.

Next came church libraries. In 1701, Rev. Thomas Bray established a system of no-fee libraries for the literate parishioners of 30 Anglican churches in the American colonies. While mostly religious collections, these "Bray Libraries" also included a few volumes of history and Latin classics.

A more common sight in the 1730s through the 1840s was the “social library,” essentially a joint stock company tied to learned societies or private associations, with books available to members who typically paid subscription fees (Ben Franklin founded one in 1731 called the Library Company of Philadelphia). Social library collections covered a more expansive range of topics including fiction, but still reflected the personal tastes of its members.

The trouble was, these mostly private libraries left the average early American without equal access to books and, by extension, to a broad range of knowledge.

By the 1850s, some social libraries expanded subscriptions to any member of the public willing to pay. A few mercantile, factory and other specialty libraries opened “reading rooms” with limited availability to the public.

Yet, the American appetite for free information access wasn’t sated.

Social libraries began to donate collections to towns. The first American town to establish a publicly funded library was Peterborough, N.H., in 1833, the first known “free library” in the U.S. In 1849, the free library movement had solid footing with a New Hampshire tax levy to support it statewide.

Massachusetts and Maine followed suit in 1854. After the Civil War, free library state initiatives spread across the nation and (free) public libraries displaced social libraries as America’s primary institution for the dissemination of books.

Where would we be without them? Equal access to full, free and broad information, censored only by one’s own judgment, is the cornerstone of a healthy democracy.

“The only thing that you absolutely have to know is the location of the library.” — Albert Einstein

• • •

Sholeh Patrick, J.D. is grateful for free libraries. Email sholeh@cdapress.com.