Huckleberries

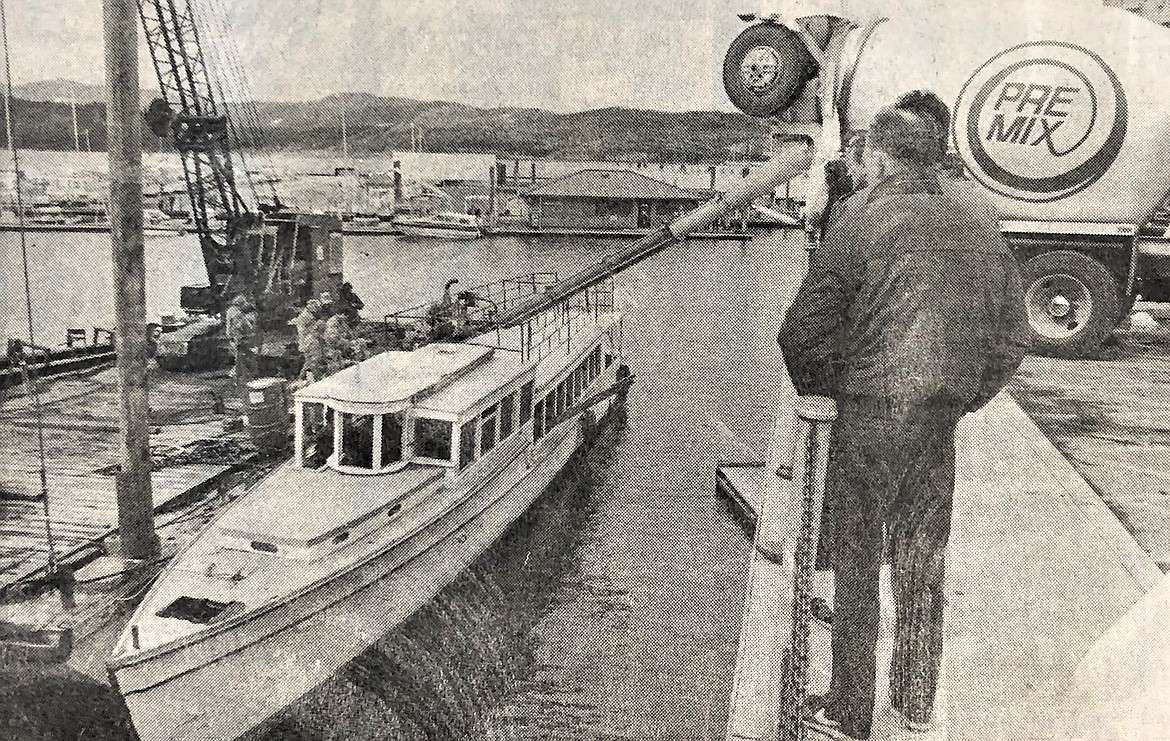

The Seeweewana did not go gentle into Lake Coeur d’Alene’s deep.

The lake’s last wooden tour boat stayed afloat for 17 minutes after it was scuttled, a quarter mile from City Beach, while hundreds watched from boats, a seaplane, the shore, the boardwalk and Beverly’s.

John Finney’s old craft fought gravity for so long that resort waiter Michael Koep quipped to onlookers: “It’s not really going to sink. It’s just a bluff to get business in here.”

It was sinking, imperceptibly.

Finally, the bow slipped under water, and a moment later, at 12:19 p.m. Friday, March 25, 1988, the Seeweewana was gone. For the last 35 years, it has formed an underwater park, enjoyed by divers, with Fred Murphy’s Rutledge and P.W. Johnson’s Spokane.

The final seconds were anticlimactic for the observers on the boardwalk, including this columnist. A brisk wind and choppy waves pushed the flotilla of 18 boats between the boardwalk and the Seeweewana, obscuring the view. The landlubbers protested, with one woman screaming, “How rude.”

Some were bothered that a major piece of Coeur d’Alene history was dispatched in that way.

But John Finney’s widow, Thelma, had tried to find a taker for the vessel, which was decommissioned in 1982 and stored at the Honeysuckle Beach boathouse. The city of Coeur d’Alene turned it down. So did the Museum of North Idaho. Before Tom Michalski, a well-known diver of that era, stepped forward to claim the boat and pay a $50 scuttling fee, Thelma had threatened to burn it.

Thelma, whose husband had died two years earlier, intentionally skipped the sinking of the Seeweewana. She told me that day: “I couldn’t. It was just too sad for me. It was just like a death.”

Originally built in 1926 and called Holly’s Comet, the Seeweewana was designed as a high-speed vessel for passengers and freight to challenge slower steamers on the run between Coeur d’Alene and St. Maries. John bought the vessel at a bargain price after better roads and autos ended her profitability.

The inspiration for the name change to Seeweewana came from Camp Fire Girls. During summers, Captain Finney would ferry them 15 minutes across the lake to Camp Sweyolakan on Mica Bay. The excited youngsters affectionately dubbed his vessel “Seeweewana” — an American Indian name meaning “traveling over the water.” And John liked it.

Now, the Seeweewana rests below the water, a symbol of a simpler time, but not forgotten.

One of a kind

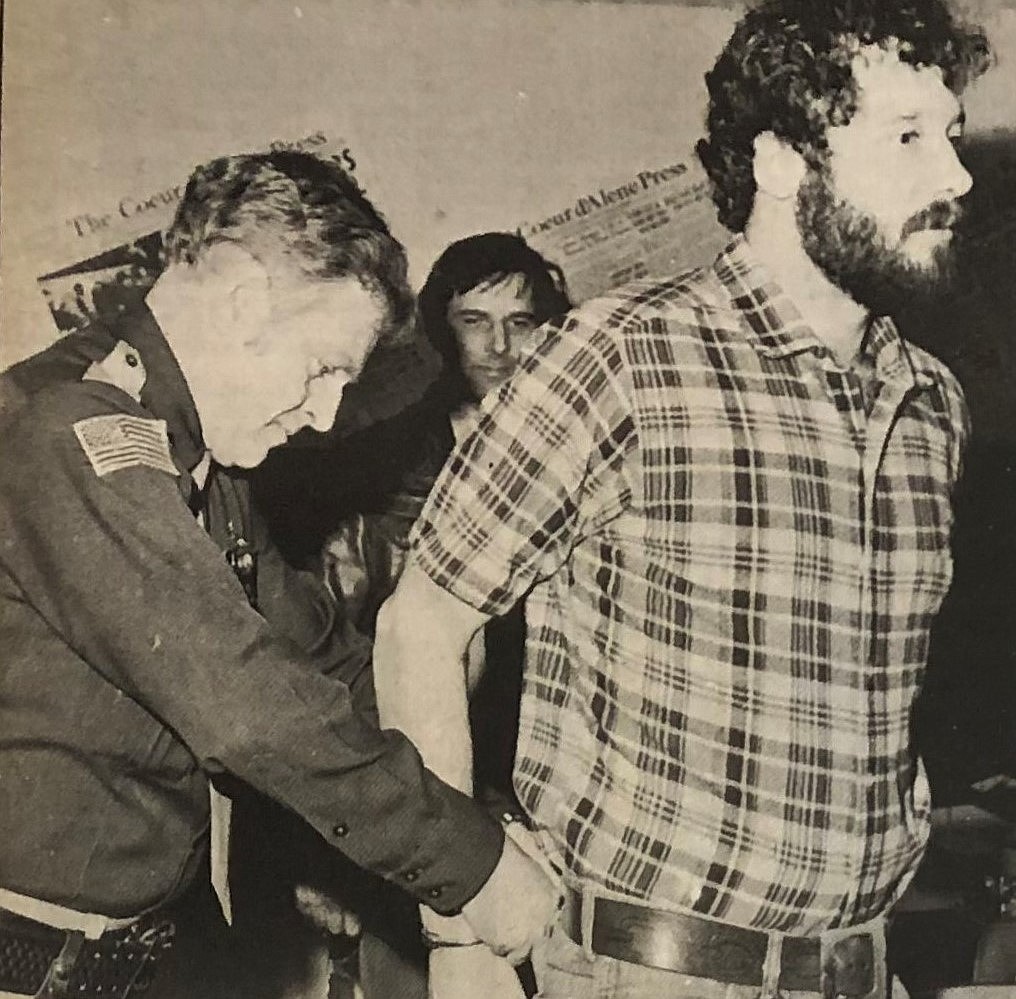

David Bond — at times my competitor, at times my colleague — admired gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson and defended underdogs. A wordsmith who battled personal demons, he could be frustratingly undependable and yet win national journalism awards. He was at his best when writing in the first person.

Forty-five years ago (March 17-18, 1978), Bond was charged with “criminal libel,” handcuffed in the Press newsroom, and taken to jail by Sheriff Rocky Watson and Deputy Phil Collins. It was a gag. D.P. had jumped at the chance to spend 16 hours in the dilapidated county jail incognito.

His subsequent feature story would begin: “I spent a year Friday night in the Kootenai County Jail.”

We’re talking about the old county jail here, an unholy jumble of small cages and misery in the basement of the equally inadequate sheriff’s office on courthouse grounds (where the administrative building is located today). The jailhouse was so pathetic that a judge would rule it inhumane for long stays and order the county to ship prisoners to the Shoshone County Jail in Wallace.

The jailers weren’t in on the joke. They treated D.P. like any other incarcerated prisoner.

“I was questioned, identified, searched, and then tossed into a tiny cage near the booking desk and stripped of all my clothes and belongings,” Bond reported. “A few moments later, I was given a set of blue coveralls with which to cover my entirely naked body — no underwear, socks or jewelry allowed.”

It wasn’t long before the heat of the cell and boredom took hold. All David could do was pace and read graffiti on the walls. He spent an hour trying to retrieve a cigarette butt just out of reach through the bars of his cell. “I can see why prisoners try to escape,” he wrote later.

Many loved him. Some hated him. But his genius for such stories shined through his contradictions.

Hear them roar

The mere mention of unlimited hydroplane racing can trigger an argument in this town still. But 65 years ago (March 20, 1958), at the start, it wasn’t like that.

Coeur d’Alene solidly backed the attempt by the new Coeur d’Alene Unlimited Hydroplane Association to land the first races for that June 14-15. The organization, headed by Commodore John Richards and Vice Commodore Duane Hagadone, believed a race would boost tourism and combat the 1958 recession.

“They felt the tourism dollars from the races would keep things going through the summer,” said local hydroplane expert Stephen Shepperd. “It was a money thing.”

Organizers had no trouble raising $10,000 to promote the races. The money arrived in $100 increments from individuals and businesses — whose names were regularly reported in Publisher Burl Hagadone’s Press. Burl would assign his son, Duane, to promote the races throughout the Inland Northwest.

Coeur d’Alene landed the races. The roar of the thunderboats and their rooster tales would be a staple of Lake City summers for a decade, 1958-68, sullied somewhat in the early '60s by troublemakers who camped at City Park and roamed Sherman Avenue after dark when their beer ran out.

But race organizers, volunteers and spectators viewed that time in this city's history as a golden age.

Huckleberries

• Poet’s Corner: One single day’s too short by far/to honor all the fools there are;/just check the news and you’ll agree/we need a month … or two … or three — The Bard of Sherman Avenue (“April Fool’s Day”).

• Limericking: Our state reps must want schools to fail./They’ve no interest in funding details./So let’s gear up the bake sales/To combat the fake tales/That their cronies will send you by mail — A Humble Spud (“Bake Sales”).

• On This Day — 75 years ago (March 26, 1948), the Press published a multi-page story, with photos, about its new headquarters at Second & Lakeside. Some 1,200 attended the open house. The move was only the second for the Press. In 1894, as a 2-year-old weekly, it moved to 111-113 Fourth St. (current home of the Canton restaurant).

• What’s in a Name? The basketball court at Coeur d’Alene High is called Jordan Court for good reason. Elmer Jordan guided the Vik cagers to state titles in 1949 and 1963, and a winning record of 425-183 (.699) over 23 years. He was beloved, too. Fifty-five years ago (March 21, 1968), he retired from CHS to start a successful career in real estate.

Parting shot

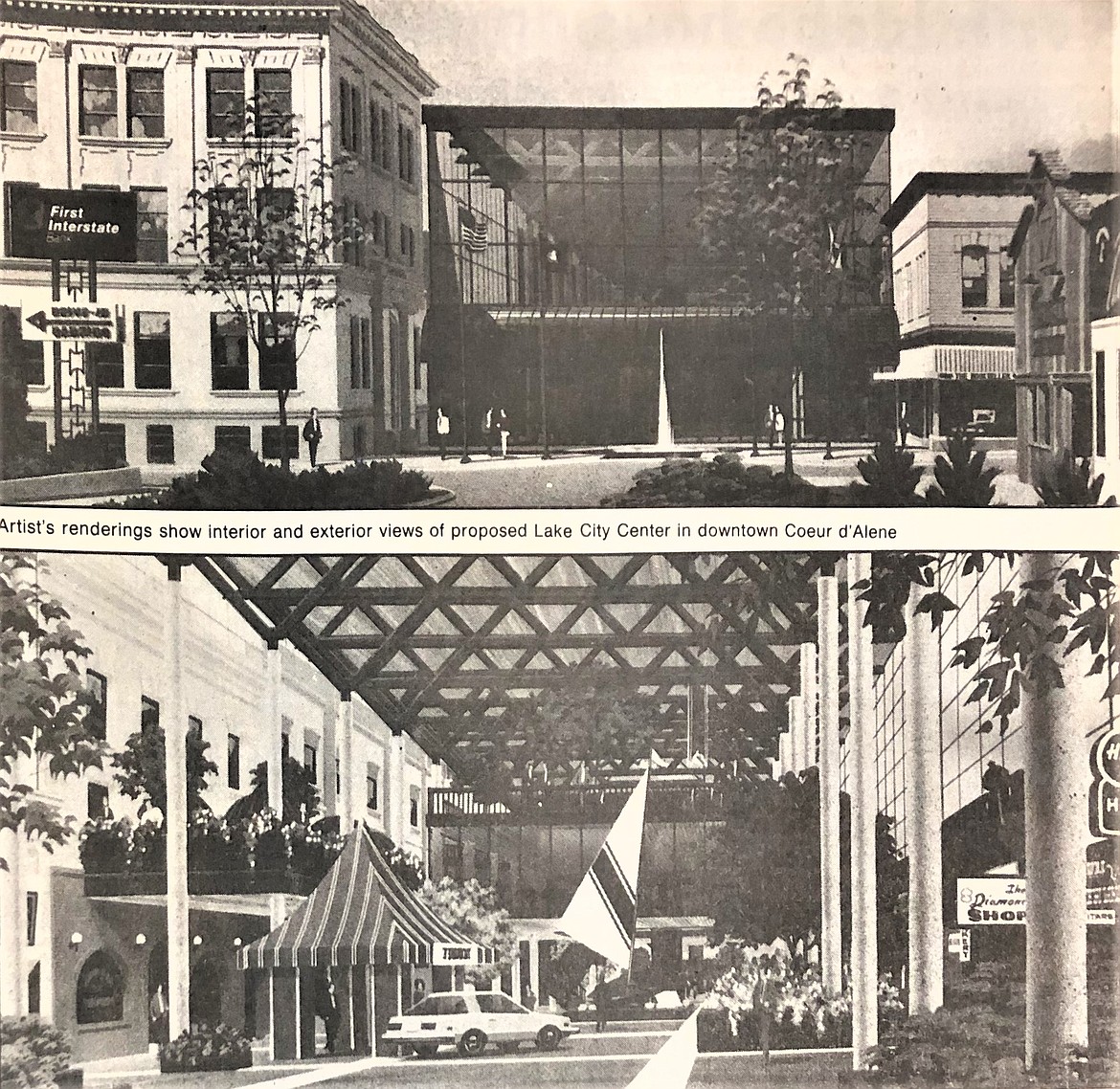

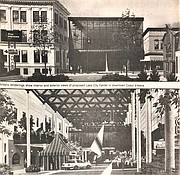

When I first landed here, in fall 1984, Jim Deffenbaugh of the Central Business Association had a plan, gathering dust on his book shelf, to build a covered mall over Sherman Avenue, from Second to Fifth. Don’t laugh. Some 40 years ago, all but one property owner of Deffenbaugh’s organization thought it was a good idea. Downtown business owners were desperate. They were bleeding customers to Spokane and other parts of town. A study showed that the downtown was only getting 20 percent of the local retail sales. And the figure was predicted to drop to 16 percent by 1985. "Revitalization" was the buzzword of the day. Traffic, of course, would have to be diverted onto Front and Lakeside avenues. And then, in 1986, The Coeur d’Alene: A Resort on the Lake opened. And, in the 1990s, Sandi Bloem led downtown revitalization. And today the downtown’s humming. Sometimes, the best action is no action.

• • •

D.F. (Dave) Oliveria can be contacted at dfo@cdapress.com.

This story has been updated to reflect a correction. Captain John Finney was the owner and operator of the Seeweewana. The original version incorrectly listed Captain Finney's nephew, Fred, as the former owner.