Huckleberries

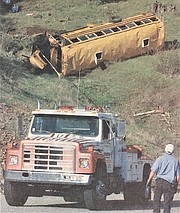

Sally Finney Johnson is still amazed that no one died 20 years ago when a school bus slid off Yellowstone Trail Road and tumbled 400-plus feet down a steep hill.

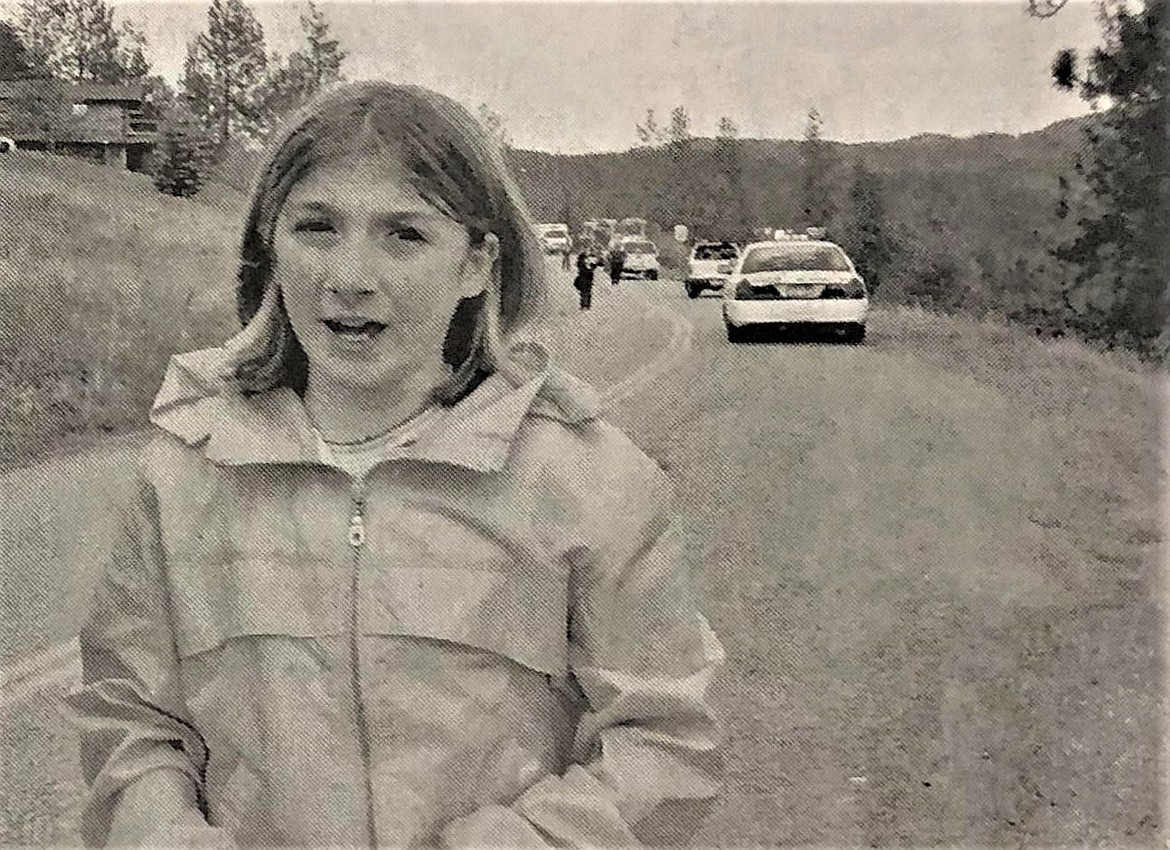

The bus was carrying a driver and seven children from Fernan Elementary, including two of Sally’s nieces and a nephew. The worst hurt was niece Kensi Finney, then 8, best friend of Sally’s daughter, Jill.

“I’ve praised God often for sparing Kensi’s life,” Sally said.

The two girls would grow into “flourishing, godly adults” who served as each other’s maids of honor and began having babies at about the same time, Sally said.

On April 15, 2003, however, Kensi was pinned in the wreckage with her foot out the window. She thought she’d lost the foot. She hadn’t. But she had suffered a lacerated liver.

The driver had just dropped off Hailey Johnson (no relation to Sally) on Bonnell Road before turning east on narrow Yellowstone Trail Road toward the Blue Creek area. The girl reported she heard “a huge crashing sound” and called Sally Johnson to say the bus may have slid over the side and that she was “really scared.”

Sally called her brother, Dave Finney, to ask if his kids had returned home. And, when he said they hadn’t, the two siblings rushed to Yellowstone Trail Road. Sally got there first and remembers the horrible scene of “four bloody kids standing on the road by themselves.” One of them was her niece.

Sally’s niece, Sarah, then 11, later described the frightening crash to a Press reporter: “I hit the seat. I hit the floor. I hit the seat. I hit the floor. It was kind of bouncing and rolling, and we were flung everywhere. I kept my eyes closed some of the time.”

When the bus stopped moving, Sarah checked on her cousin, Kensi. Next, she looked after Mikey Foster, then 10, who was lying still. “Are you alive?” she yelled. The boy responded, “I’m alive. Am I awake?”

Moments later, Kensi’s father, Dave, rushed down the hill, prayed and extricated his child, with engine oil dripping down on them.

Only the driver had a seatbelt in the 1994 GMC Bluebird bus. Later, the transportation director would say the district had had many discussions about seatbelts for the children. But opted not to install them. “We don’t believe in them,” the director said. “They’d have been hurt worse if they were wearing belts.”

Indeed, it could have been much worse.

All seven children and the driver suffered at least cuts and bruises. Some sustained deep cuts that required stitches. And there was a broken collar bone, a broken tooth and, of course, a lacerated liver and a smashed foot. But all mended quickly, even Kensi, who did not need surgery.

Later, Sally’s sister-in-law, Marilee Finney, wrote a poem, “Psalm 2003,” listing two dozen ways that God had protected her family and others.

“I’m just grateful for the way God spared the lives of all the kids,” Sally Johnson told Huckleberries. “I think of it every single time I drive by that spot in the road. I love my nieces and nephews so much, and it’s such a blessing to see them living productive lives and raising their own beautiful children now.”

Hydromania

Coeur d’Alene was “cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs” 65 years ago when news arrived, in the form of a 60-point, double-deck Press headline, that the town had landed an unlimited hydroplane race.

Representing the Coeur d’Alene Unlimited Hydroplane Association, Lee Brack and Duane Hagadone had visited the hydro gods in Detroit, Mich., caps in hands, to lobby for the race. The front-page headline April 14, 1958, shouted Detroit’s decision: “Diamond Cup Race Approved.”

The American Power Boat Association sanctioned the first Diamond Cup for June 28-29 of 1958. The locals had wanted the dates of June 14-15. But they were satisfied that the ones offered would dovetail into the Fourth of July celebration and ordered 24,000 more booster buttons.

A day earlier, Coeur d’Alene area hydromaniacs proved their love for the sport by trooping to Hayden Lake — 40,000 strong — to watch hydroplane Miss Spokane christened and then, piloted by Capt. Dallas Sartz, clock up to 140 mph in three runs during her first public test.

Reach for the sky

Few remember the name Terry Phillips today. But in fall 1981, the developer was the focus of an environmental backlash that swept a Save Our Shoreline ticket into City Hall.

Many in the town were outraged after Phillips won approval for two, 14-story towers to be built just east of what is now The Coeur d’Alene Resort. Ultimately, Phillips was ensnared by litigation and sold his property to Duane Hagadone.

Forty years ago, in spring 1983, Hagadone’s plans to build a high-rise of up to 24 stories on the old Phillips property enraged enviros again. Hagadone said the town backed him. And the enviros insisted that he pay for a community vote to see if that was so. One public meeting lasted five hours and attracted 500 residents.

The controversy raged until a stunning development knocked it off Page One.

On June 5, 1983, after a fierce behind-the-scenes battle, Hagadone gained control of Bob Templin’s Western Frontiers company, including the old North Shore resort. And built his waterfront empire.

Huckleberries

• Poet’s Corner: Dear IRS,/here’s all my money,/please don’t let them/spend it funny — The Bard of Sherman Avenue (“April 15”).

• Limericking: Joe Biden’s an affable matey./And the work that he does is quite weighty./But some people do wonder/‘Cuz he does tend to blunder,/Can he still do this job over eighty? — The Humble Spud (“EIGHTY”).

• Champagne Music: Yes, Virginia, there once was a North Idaho Accordion Band, comprised of 40 members, all wearing red corduroy jackets, with gold braid and buttons, black trousers, and Coeur d’Alene Commodore caps. On April 16, 1953, the band was headed to Tacoma to compete against other Northwest and California accordion bands for bragging rights. Cue up Lawrence Welk.

• Milestone: An institution was born in Coeur d’Alene 75 years ago (April 12, 1948) when Jack Adams opened Coeur d’Alene Tractor in a concrete block building at 2103 Fourth St. Adams had been associated with the Adams Tractor Co. in Spokane. He told the Press that he would move his wife and four children to Coeur d’Alene once school was out.

• In Memoriam: James LePard and Gary Frame are both gone now, after Gary’s passing at age 83 last Dec. 21. But 55 years ago (April 9, 1968) the two men were in their prime as they announced a partnership that would make LePard & Frame Consulting Engineers (now Frame & Smetana) a gold standard for local businesses for decades to come.

Parting shot

And here we are three years later. On April 17, 2020, as the COVID pandemic took hold, Huckleberries debuted in the Coeur d’Alene Press after a 35-year run in The Spokesman-Review. Former editor Mike Patrick secured Duane Hagadone’s blessing for the move. And the column launched, featuring a tutorial on the proper pronunciation of “Coeur” in Coeur d’Alene. Also, it offered items about the toilet paper shortage, Councilwoman Kiki Miller’s troubled pandemic dreams, and a semi-isolated Dover woman who threatened to shave her head because “nobody can see me. And it’ll grow back.” The pandemic has waned. And the unlikely marriage of Huckleberries and the Press remains strong. Onto year four.

• • •

D.F. (Dave) Oliveria can be contacted at dfo@cdapress.com.