Blind, but they can see

COEUR d’ALENE — As Mackenzie Gibson takes a few steps from her daughter, she turns and says, “I’ll be right back.”

Aubri, blonde and 7 years old, nods.

“All right mom,” she says.

Olivia, her 6 year old sister, remains next to her.

“I’m way older than her,” Aubri says.

As adults mill around the room, the Hayden girl continues using a brailler, similar to a typewriter, to produce braille.

She is learning this system of raised dots that represent letters and can be read with fingers because she is blind.

“I love making letters," she said.

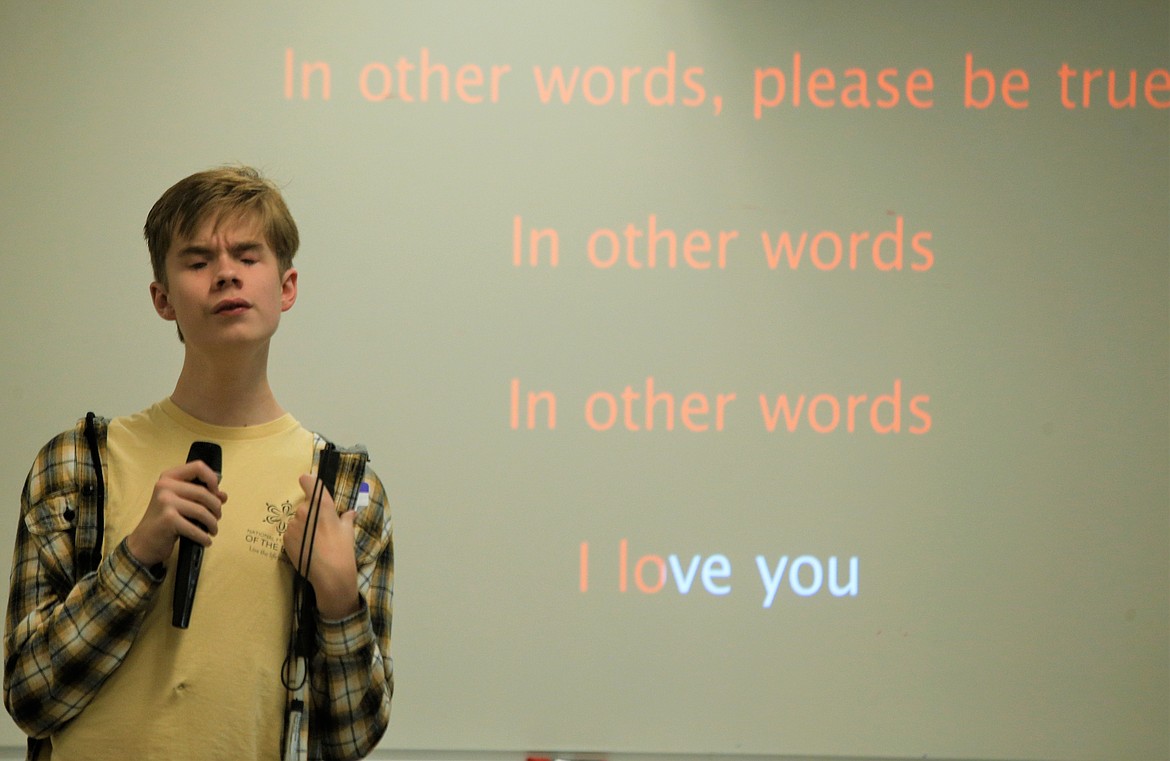

Aubri was among a small group of blind and visually impaired who took part in “Celebraille” on Saturday in the DeArmond Building at North Idaho College.

The event was organized by Jordana Engebretsen, president and owner of Vocalife, whose mission is to “empower students with visual disabilities and enrich his or her vocational and/or life goals.”

About 50 people attended the hourlong gathering that saw her students sing, play keyboards and share the history of braille.

Jordana Engebretsen, who is blind, pointed out it is Blindness Awareness Month.

“There are some people in the community that can’t see, totally blind," she said. “But we have the same needs and we can do the same things.”

Those who can’t see still have vision and can still do “absolutely everything,” Engebretsen said, citing algebra, music and math. “Anything you want to do.”

According to the American Federation for the Blind, there are about 40,000 blind and visually impaired people in Idaho.

Engebretsen, a teacher for the blind, said there are four blind students at Post Falls High School and they do well.

“They are amazing, what they can learn,” she said.

Braille was invented in 1821 and is named after its creator, Louis Braille. It has opened not just doors, but worlds, Engebretsen said.

“We are really blessed we have braille in our community and we have braille in our schools,” she said.

But it's not universally known. The Celebraille program was in braille and only a few, mainly students and family, could read it.

“We need to promote braille for our kids,” Engebretsen said.

Annee Hartzell, a teacher for the visually impaired, shared her story.

She said she was born three months early and had vision in one eye until fifth grade. Then, she lost all sight, "in a matter of minutes."

"It changed my life,” she said.

But Hartzell said her mom was a taskmaster and wanted her to remain with her peers. She required her daughter to read and write book reports in braille.

“I think that was the biggest gift she ever gave me. I spent that whole summer reading," Hartzell said.

She often struggled to read one letter at a time, but refused to give up. She went to college and went into education.

“I have not looked back,” she said.

Hartzell, who loves to cook and travel, said thanks to technology, it’s a good time to be a blind person.

“The world is more open than it’s ever been in so many ways, but we have to give our kids the tools that they need,” she said, urging people to advocate and promote use of braille.

She wants people to understand that “the power of braille can be such a liberation for a blind person or a visually impaired person.”

Mackenzie Gibson said Aubri was born blind, but they didn’t know it until she was six months old after taking her to a specialist.

That forced some lifestyle changes.

“I wasn’t creative until she was born,” Mackenzie Gibson said. “I learned how to be creative and how to do things differently.”

Today, Aubri is outgoing, involved in dance and jiu-jitsu.

“She’s actually pretty open about showing friends her different life,” Mackenzie said.

Aubri overcomes tough times. About seven months ago, she told her mom she didn’t like being blind.

“It’s been a struggle for her,” Mackenzie Gibson said.

The second grader began attending the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind in Gooding, earlier this year. While she is escorted to and from her plane seat, she flies, unaccompanied, there twice a week. She is courageous and calm, says her mom.

“It’s the hardest thing, I’ve ever done as parent, sending her to Boise,” her mom said.

But with limited resources in North Idaho it’s necessary, she said, and it’s helping her daughter.

“She has totally thrived and loves learning," she said.

Mackenzie Gibson said it's important to treat the blind and visually impaired the same as everyone else.

“A lot of people in the community see our kids and think they have to dumb things down,” she said. “To be inclusive is to treat them the same and to make an equal playing field.

"It doesn’t mean it’s fair for everyone, but it’s equal for everyone," she continued. "And that’s really hard for people to learn with these blind kiddos. They underestimate them, a lot.”

Saturday, no one underestimated Aubri.

“She’s a strong little one,” her mom said.

Tina Johnson, a teacher for the visually impaired, has worked with Aubri since she was 6 months old.

“Amazing young lady,” Johnson said.

She encouraged Aubri as she used the Perkins Brailler, praising her as she produced names and words.

When Aubri was done, Johnson picked up the white sheet of paper with the raised dots and read it.

“Look what she wrote,” she said, beaming with pride. “It says, ‘I love you.’”