NIC’s future uncertain if accreditation is lost

COEUR d’ALENE — If North Idaho College loses accreditation, two things are certain: credits earned won’t be transferable and students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid.

Beyond that, the path is foggy.

“This is uncharted territory,” said Mike Keckler, chief communications and legislative affairs officer for the Idaho State Board of Education. “There’s nothing in statute, no framework in place for how we would manage the loss of accreditation and what it would mean for the school.”

In Idaho, all public postsecondary institutions must be accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, a federally recognized accrediting body that sanctioned NIC with a warning in April, largely due to dysfunction on the board of trustees.

The NWCCU sent a letter to the college Saturday, cautioning that recent actions by the board of trustees do not align with the eligibility requirements and standards for NWCCU accreditation.

NIC has until Jan. 4 to respond with an explanation for how it is not out of compliance.

The matter of North Idaho College’s accreditation looms large in the wake of that letter, with a site visit from the NWCCU set for March and the board embroiled in conflict related to an abruptly hired attorney, a president suing to return to his job after being placed on administrative leave, votes of no confidence from college faculty and staff, suspended policies and a string of possible open meeting law violations.

Even if accreditation is lost, students already enrolled at NIC would be able to complete their degrees, according to the State Board of Education. Degrees earned before the loss would remain valid.

But dual-enrollment programs for high school students would cease to exist, as would satellite programs with other colleges.

NIC’s nursing program is accredited separately by the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing, but it’s unclear how long the program could survive without the college.

The full impact of accreditation loss is hard to envision because it hasn’t happened in Idaho.

“I’ve never heard of something like this happening, where one lost accreditation,” Keckler said.

Amid concerns about accreditation, another question has swirled in the community: If North Idaho College fails, what happens to the land on which it sits?

To answer, it’s necessary to look back at the college’s history.

In October 1937, Winton Lumber Company donated a 32-acre tract of land in the abandoned Fort Sherman military reservation to Kootenai County for the purpose of developing a public park, hospital or educational institution.

For centuries, the people of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe gathered to hunt, fish, dance, play games, feast and swim in that area, where the lake feeds into the Spokane River.

The special site was called Yap-Keehn-Um, which means “the gathering place.” The beach still bears that name.

Coeur d’Alene Junior College was founded in 1933. By early 1940, the renamed North Idaho Junior College had outgrown its original space on the third floor of Coeur d’Alene City Hall.

In “The Gathering Place: A History of North Idaho College,” Fran Bahr describes how the search for a permanent home for the college came down to two choices: the city-owned mill site near Tubbs Hill, which is now McEuen Park, or county-owned Winton Park.

An informal vote revealed that Kootenai County residents preferred the park, which was spacious enough for future expansion.

The county conveyed the land to the North Idaho Junior College District in August 1941.

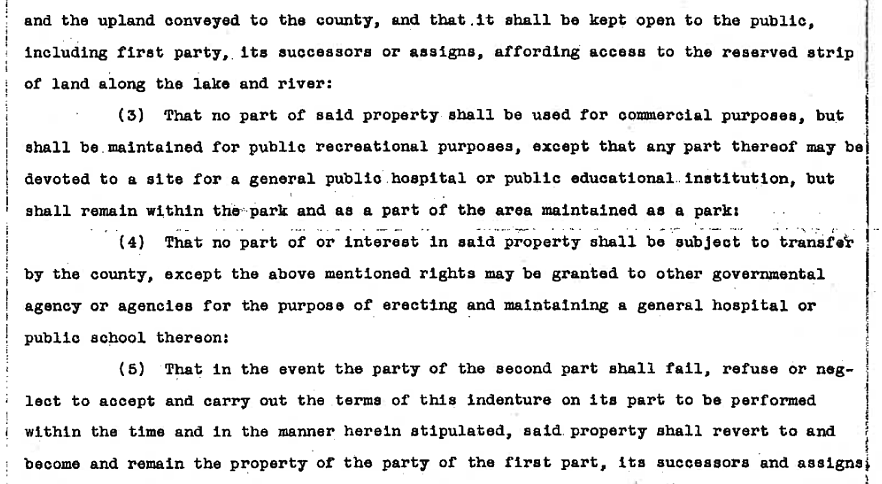

In the event of the failure of the college, county records show, the property reverts to Kootenai County.

The first structures on the new campus were a two-story administrative/classroom building and a vocational arts building, which cost around $135,000 combined. That’s around $2.8 million in today’s dollars.

In the present day, the college itself owns all buildings on campus, with the exception of those financed through the Division of Public Works or the Dormitory Housing Commission.

The only such building now is NIC Student Wellness and Recreation. It will belong to the college when the bond is paid.

Under Idaho law, the trustees of each community college district have the power to acquire, hold and dispose of real and personal property. They also have the power to convey and transfer real property upon which no college buildings used for instruction are situated to nonprofits, school districts, junior housing commissions, counties or municipalities, as well as to lease real property not used for instructional purposes for terms determined by the board.

Colleges that lose accreditation tend to close. A Wall Street Journal survey of 18 institutions that lost accreditation between 2000 and 2015 found that half closed. The surviving schools had an average graduation rate of 35%.

Community colleges that lose accreditation also appear to be rare. City College of San Francisco, a two-year college with around 85,000 students and 11 campuses and sites, came close in 2013.

The college had received sanctions from its regional accreditor, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, which accredits institutions in California, Hawaii and American territories in the Pacific Ocean. The San Francisco community college was sanctioned for numerous problems, according to Inside Higher Ed, including “dangerous budget deficits, a balky governance system and a failure to track student outcomes.”

Though the college remained out of compliance in many areas, its accrediting commission ultimately granted a two-year extension to resolve the issues and avoid a shutdown. In 2017, the commission reaffirmed City College of San Francisco’s accreditation for seven years.

At North Idaho College, the future remains uncertain.

For now, residents and state-level leaders alike are watching, waiting and hoping that the college retains accreditation — because the alternative is nearly unimaginable.

“We just don’t know what it would entail,” Keckler said. “I pray we don’t have to find out.”