Big opportunities for big game hunters

Deer and elk hunters should be optimistic and concerned about the 2022 hunting seasons. They will have mostly healthy, stable elk herds and potential growth in mule deer herds and harvest, but white-tailed deer hunting in portions of Clearwater area are unlikely to have recovered from a disease die off last year, and chronic wasting disease was detected for the first time ever in Idaho last year, which will have to be managed.

That’s a brief summary of what lies ahead for fall elk and deer seasons, and elk and mule deer hunters can safely anticipate hunting similar or slightly better than last year.

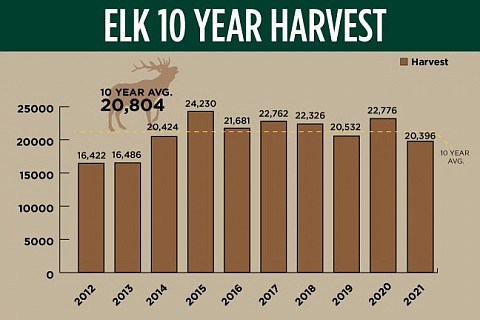

That’s due in part to stable elk herds that have produced harvests above 20,000 elk annually for the last eight years. The elk harvest dropped about 10 percent last year, but was well within the usual year-to-year fluctuations and just below the 10-year average of 20,804 elk.

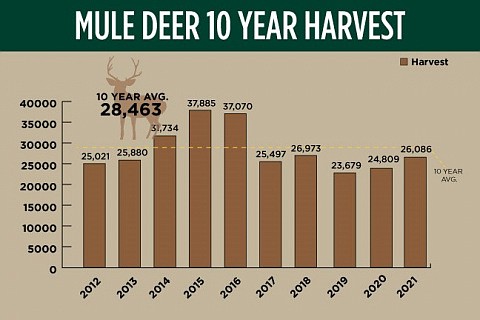

Mule deer herds continue to trend in the right direction after a tough winter in 2016-17 that led to a 30 percent decline in harvest in 2017, then another tough winter in 2018-19.

The drastic harvest decline in 2017 was partly by design as Fish and Game biologists slashed antlerless mule deer tags in an effort to preserve does and rebuild herds. That effort, along with three consecutive mild-to-moderate winters in southern Idaho, has led to increased harvest over the last three years, and this fall could easily mark the fourth.

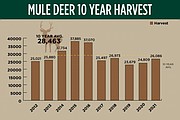

But although mule deer harvests are trending up, they’re still below the 10-year average, but could return to it this fall with a modest bump in hunter success.

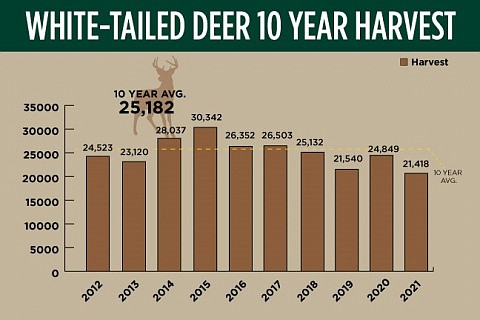

Despite a serious die off of white-tailed deer in portions of the Clearwater and Panhandle Regions, the overall whitetail population remains solid, but with some significant holes in the population as some localized whitetail herds were hit hard by epizootic hemorrhagic disease last year and are unlikely to recover this fall.

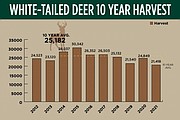

How big of an effect that will have on the fall whitetail harvest remains to be seen. While there was a 14 percent drop in harvest between 2020 and 2021, it’s possible that it could bounce back to near the 10-year average in 2022.

Highs and lows: Last year’s harvest

In 2021, hunters harvested 20,396 elk, 26,086 mule deer and 21,418 whitetails. Despite taking a 10 percent hit, elk harvest was still above the 10-year average; deer harvests were slightly below. Success rates were 23 percent for elk hunters, 36 percent for mule deer hunters and roughly 40 percent for whitetail hunters.

Elk hunting

Elk populations tend to swing less drastically and sporadically than deer, and have stayed relatively consistent in recent years. And last year marked the eighth year in a row where elk harvest eclipsed 20,000, which has happened only one other time dating back to the 1930s.

Although slightly fewer hunters took home slightly fewer elk, 2021 still showed to be in line with the 10-year average (20,804). Antlered elk dropped only slightly, from 11,897 in 2020 to 11,142 last year. Antlerless elk saw a slightly bigger drop (roughly 14.9 percent) in harvest numbers, from 2020 to 2021. Earlier that year, Fish and Game officials introduced new seasons aimed at reducing the number of elk in certain areas where they are well above objective or are infringing on private property.

Fish and Game Deer/Elk Coordinator Toby Boudreau believes we will see much of the same, if not better conditions for elk this fall.

“Elk populations are stable-to-increasing. With better science and more camera estimates, I think we are trending to more elk than we’ve ever seen in Idaho,” he said.

Overall, hunters can expect to see another impressive year, similar to 2021. A wet spring will also be good for antler growth, and there’s likely more younger bulls out in the field this year.

Speaking of young bulls, next to hunter harvest reports, trapping and collaring elk calves is the most reliable tool Fish and Game biologists use to estimate survival. Elk have not been trapped and collared for as long as mule deer, and elk calves typically survive at a higher rate than mule deer fawns.

Last winter’s 78 percent survival is at the upper end of that range and indicates a growing elk herd. (By comparison, survival rates ranged from a low of about 52 percent to a high of 84 percent in 2014-15.)

Many are wondering if this year’s high winter calf survival is going to potentially pave the way for another 20,000-plus harvest year, which would be only the second time in history that elk harvest over 20,000 has spanned nine consecutive years.

“Elk numbers are sustainable right now,” said Boudreau, and added that many elk populations have shifted over the last four decades.

“We’re seeing elk in different places than they’ve historically been, and their numbers are still on the rise,” he said.

The general redistribution of elk throughout the state is not a bad thing and can be linked to a handful of factors.

“Wildfire,” Boudreau says, “is a wildcard that can have a heavy impact both on mule deer habitat and elk habitat.”

A large wildfire can wipe out large portions of bitterbrush and sagebrush and initially regrow as grass that provides a better diet for elk. While this is bad news for mule deer, elk often thrive in these situations.

“Because of this shift in forage, we’re seeing elk relocating to these drier, post-wildfire regions that mule deer don’t find as suitable,” Boudreau said.

Elk are also finding agriculture lands too tempting pass up, and harvests in recent years also includes a higher number of depredation hunts where elk are damaging crops.

But overall, there remains plenty of elk for hunters to pursue in most regions of the state, including lots of general hunting opportunities. Elk hunters need to be diligent at finding areas where elk want to be, and not dwell in areas where the hunters want them to be, but the elk aren’t there.

By the numbers

Total elk harvest in 2021: 20,396

2020 harvest total: 22,776

Overall hunter success rate: 22.9 percent

Antlered: 11,142

Antlerless: 9,253

Taken during general hunts: 12,778 (17.6 percent success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 7,619 (41.5 percent success rate)

How it stacks up

Although slightly fewer hunters took home slightly fewer elk, 2021 still shows to be in line with the 10-year average (20,804). Antlered elk dropped only slightly, from 11,897 in 2020 to 11,142 last year. Antlerless elk saw a slightly bigger drop (roughly 14.9 percent) in harvest numbers, from 2020 to 2021.

Mule deer hunting

Mule deer hunters could easily see themselves in a half empty/half full dilemma, but for sake of discussion, let’s go with half full.

“Overall, things are looking pretty good,” Boudreau said. “We’re on the upswing of the population cycle.”

Hunters harvested 1,277 more mule deer in 2021 than in 2020, an increase of 5.1 percent; however, mule deer harvest numbers across the state were still about 8 percent below the 10-year average (28,463).

Boudreau expects this year’s harvest will meet or exceed last year’s and the 10-year average.

That’s because mild winters mean higher fawn survival and larger herds. About 70 percent of radio-collared mule deer fawns survived their critical first winter this year. The long-term average is about 57 percent.

Fawn survival was also slightly higher than last year, and the last three years have been above or near the long-term average, which translates to a growing mule deer population.

But that doesn’t mean every thing is perfect to rebound herds. Boudreau explained winters are critical because that’s when the most deer die, but summers with good forage are also important for the growth of individual animals, which improves their hardiness and fitness to produce healthy fawns, and increases antler growth for bucks.

“Every mild winter is a blessing, and every wet summer is a bonus,” he said.

Those recent mild winters have been coupled with fairly dry, hot summers, so herd growth may be modest, but Boudreau said he’s confident that there will be more deer available for hunters, and the late, wet spring may boost antler growth.

Boudreau added that survival of fawns throughout the state is not uniform depending on the unit where the fawns were collared. Some of the highest survival occurred in Southwest and West Central Idaho, while survival was closer to normal in the Magic Valley and eastern portions of the state.

Boudreau is also concerned with the long-term quality of prime mule deer habitat, particularly large wildfires in recent years that converted sagebrush and bitterbrush habitat – a favorite for mule deer – to grasslands that favor elk. Loss of quality habitat and can slow the recovery of deer herds and make them more susceptible to winter kill over time because deer have less forage to build and maintain fat reserves and survive difficult winters.

But hunters can look forward to the odds of having a larger mule deer harvest working in their favor this fall.

By the numbers | 2021 Harvest

Total mule deer in 2021: 26,086

2020 harvest total: 24,809

Overall hunter success rate: 36 percent

Antlered: 21,801

Antlerless: 4,284

Taken during general hunts: 19,865 (28.5 percent success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 6,219 (49.8 percent success rate)

How it stacks up

As biologists predicted before the 2021 season, the statewide mule deer harvest increased in 2021, but the big story here is the amount of hunters versus the amount of mule deer harvested in 2021.

A total of 79,825 hunters set out for mule deer during the 2021 season — a 9.9 percent decrease from 2020, but 36 percent of those hunters went home with a mule deer, which was significantly higher than in recent years and points to improved hunting that should continue in 2022.

Also, mule deer hunters in 2021 recovered Idaho’s top deer harvest after whitetail hunters claimed that spot in 2020. A total of 79,825 mule deer hunters in 2021 harvested 26,086 mule deer. Their 36 percent success rate (general and controlled hunts combined) was the third highest in the last 11 years for mule deer.

White-tailed deer hunting

White-tailed deer populations are typically a little more stable than mule deer populations, but they are still affected by weather and disease, as we saw in 2021 when a significant outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease killed an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 whitetails, mostly in portions of the Clearwater Region.

Continuing into 2022, whitetails will be on a slow, yet uphill trend as their herds rebuild, which will hopefully occur fairly quickly. Whitetail populations have recovered from previous EHD die offs in about 3 years, and not all places where the disease hit will see a full recovery that soon.

Despite the outbreak, and estimated 54,223 hunters harvested a total of 21,418 white-tailed deer in 2021— a 13.8 percent drop from 2020. It’s not all doom and gloom though. Like elk and mule deer, white-tailed deer have still shown impressive numbers above the 20,000 mark (as shown in the chart above), still averaging 25,182 harvested in the past 10 years. And a lot of those bucks aren’t small, either, because mature bucks still take up a considerable share of the harvest.

Overall, this year’s whitetail hunting can probably be summed as good, but with an asterisk. If you’ve traditionally hunted an area that was hit by EHD, you probably should hunt elsewhere.

“We found a large percentage of whitetails that died from EHD were found at lower elevations which is predominately private land,” Boudreau said.

But Idaho’s white-tailed deer population outside the Clearwater region is looking healthy assuming EHD does not resurface again this summer, and whitetail hunters typically enjoy high success rates due to (relatively) healthy whitetail populations, generous season lengths and lots of either-sex hunting opportunities.

Last year’s EHD outbreak took its toll on whitetails, affecting roughly 5 percent of the state’s white-tailed deer population, but the drop could be short lived and unnoticeable to most hunters.

“Whitetails are incredibly prolific, and don’t always die when infected with EHD,”Boudreau said “Assuming we have more mild winters and limited outbreaks of EHD, we should expect white-tailed deer to rebound by about 2025.”

Boudreau says that hunters can still expect to find strong numbers of whitetails in and around the Clearwater region, but should avoid lower-elevation areas. Alternatively, lower elevations in the Salmon River and Snake River corridors are proving to have ever-increasing amounts of whitetail presence, and should be considered good destinations for white-tailed deer hunters this fall.

By the numbers

Total white-tailed deer in 2021: 21,418

2020 harvest total: 24,849

Overall hunter success rate: 39.5 percent

Antlered: 14,053

Antlerless: 7,365

Taken during general hunts: 19,449 (38.9 percent success rate)

Taken during controlled hunts: 1,969 (45.8 percent success rate)

How it stacks up

Fish and Game wildlife staff will continue to monitor the EHD and CWD situation among deer and elk populations during the summer and fall, as well as evaluate fawn survival rates upon the conclusion of this winter.

CWD Update

Chronic wasting disease was detected for the first time in Idaho in hunting Unit 14 and a total of five animals including mule deer, white-tailed deer and elk tested positive for this fatal neurological disease that affects deer, elk and moose.

Hunters can have their harvested deer, elk and moose tested by Fish and Game for free. Hunters must provide the head of the animal for testing, or remove the lymph nodes. Meat can not be tested for CWD, only lymph nodes or brainstem.

Fish and Game has been testing for CWD for more than 20 years, and that work will continue throughout Idaho.

The U.S. Center for Disease Control states there has been no reported cases of CWD infecting people. However, CDC recommends that people do not eat meat from an animal that tests positive for CWD.

Panhandle

Elk

Hunters should expect good elk hunting this fall. Elk tend to be more resilient to tough environmental conditions than deer. Numbers remain strong in the Panhandle with Units 1, 4, 5 and 6 being among the 10 top elk units in the state by harvest. Calf survival has remained good (above 80%) the past two winters and hunters should see plenty of spike elk and other elk available for harvest.

Deer

Some portions of the region experienced elevated white-tailed deer fawn mortality during winter and as a result, hunters might notice fewer yearlings in the woods in certain areas. This is likely due to the extreme drought conditions the region experienced last spring and summer, coupled with heavy snow that started relatively early and persisted throughout the winter into early spring.

With that said, Unit 1 continues to be the top white-tailed deer unit in the state. Units 2, 5 and 6 continue to earn top spots to harvest white-tailed deer, as well. Hunters should still be able to find plenty of deer and should see a good mix of age classes.

What hunters should be aware of this fall

While there haven’t been a lot of large fires in the Panhandle by late summer, things are drying out and hunters should keep an eye on conditions in the areas they like to hunt.

As always, hunters are encouraged to remain vigilant in their bear awareness and identification skills. In the Panhandle, grizzly bears are most commonly found in Unit 1, but have been infrequently found in Units 2, 3, 4, 4A, 6, 7, & 9. Black bears are common throughout most of the region.

As a reminder, hunters should become familiar with Fish and Game’s Large Tracts Program with timber companies, which have motorized restrictions in place set by the landowner. It is the hunter’s responsibility to know and abide by these restrictions.

It is important to remember that these properties under the Large Tracts Program are private lands, and to help keep them open to public access, users should respect the land and any restrictions that are in place. For more information, visit the Large Tracts Program webpage.

-Micah Ellstrom, Panhandle Regional Wildlife Manager