THE VETERANS' PRESS: Reflections from a World War II Prisoner of War

It was early morning on Dec. 21, 1944, and U.S. Army 2nd Lt. Joe Zelazny was headed back to his battalion near the small town of Martelange, Belgium. Just five days earlier, the Battle of the Bulge had begun when Germans launched a massive artillery attack against the Allied troops that stretched 80 miles across Belgium, Luxembourg and France.

Officer Zelazny and his driver had their jeep loaded with radio equipment, a communications man, and a wounded lieutenant. They never made it back to camp.

"We ran into German paratroopers," Zelazny remembers. The three men were captured while other American soldiers were gunned down on the spot. "A whole company right in front of us. They wiped them out. Then they put us up against a wall and shot us."

This came to be known as the Maelmedy Massacres. German soldiers shot American POWs and just left them in the snow to die.

Zelazny was shot in the left shoulder. The bullet had hit his clavicle and came out under his arm. "They let us lay there, thinking we were dead. Four hours later, a German officer turned us over and realized we were still living." Two survived, one died.

"They put us in a building, and we sat there watching them kill everybody." Joe was sent to Stalag XII-A in Limburg, Germany. He received no medical care while a POW. He sat in a 6-foot-by-6-foot room for 10 days waiting to be interviewed. On the walls were the names of other men who had occupied the same space.

Days later, Zelazny and other prisoners were transported by box cars to Oflag 64 in Poland.

Lorrayne Zelazny was at work in Tacoma, Washington, when the telegram was delivered to her home. It was Jan. 8, 1945 — on the one year anniversary of their marriage.

Lorrayne asked her mother to read the telegram. Her mom opened the letter and said "…we'll bring it to you." Lorrayne said she felt numb when her mom said "Joe's missing." But also felt that he was OK — that he'd be back.

In February 1945, Zelazny and other prisoners were ordered out of the Poland camp. It was a bitter winter with freezing temperatures. The men were weak with very little clothing. They were thankful to find dead horses along the way. They ate raw horse meat.

After covering 230 miles in 28 days, Zelazny and another officer decided they'd had enough. They refused to go any farther. They were taken by train to Stalag III-A, south of Berlin.

In early May, Russians liberated the camp and Zelazny and other officers walked 50 miles to the American lines. Joe weighed 190 pounds before his capture; 105 when he was liberated. He sent two telegrams to his wife letting her know he was alive and coming home. He arrived before the telegrams reached her. "I called her on the phone, but she didn't believe it was me."

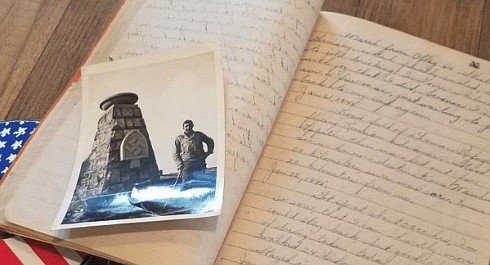

Fast forward 76 years as I sit with iced coffee at McDonald's with Joe's daughter, Kathy Thomas (Lberty Lake). We pore over the newspaper clippings, photos, her father's journal as she shares this amazing story. We talk about her dad's 21 years of service, retiring in 1963, and his devotion in working for Veterans' rights, establishing a Veterans Memorial at the Coachella Valley Cemetery (California) and one at the Tacoma War Memorial Park.

In 2009, he received the Meritorious Service Award from the National Association of Prisoners of War. Joe, along with other veterans, brought his story to local schools to educate and bring remembrance and honor.

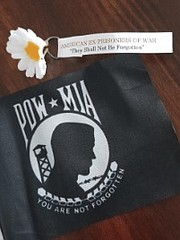

Kathy said that when her father passed away in 2015, she and her siblings found a bag of daisy lapel pins and attached ribbons with the tagline "American Ex-Prisoners of War — They Shall Never Be Forgotten," and a handout with the following statement:

"The daisy was chosen as a national symbol of all former POWs. The Military Code of Conduct required that only name, rank and serial number be divulged to the enemy. American folklore has long deemed that 'daisies won't tell,' making it a tribute to the memory of those who have endured the hardships of captivity in silence."

Kathy went on to say that in the early '90s, her father's local POW Chapter passed out daisy lapel pins on the third Friday of September (National POW/MIA Recognition Day) just as poppies are passed out on Veterans Day.

"In his honor, our family is resurrecting this grassroots initiative called the POW/MIA Daisy Campaign."

Editor's note: Army Veteran and former POW Lt. Col. Joseph John Zelazny Jr. passed away on March 20, 2015. Parts of this story were originally published on Dec. 16, 2014, in The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, Calif.): "Remembering the Battle of the Bulge on the 70th anniversary."

•••

Joe found hope

In his own words and a winning entry from a "most memorable Christmas" competition of Tacoma's The News Tribune (circa 1960), Joe Zelazny wrote:

"The Christmas of 1944, I was a wounded POW sitting in a railroad station at Limburg, Germany, with numerous other American POWs. We were awaiting the arrival of a troop train to take us to Stalag XII-A for solitary confinement.

"The activity was rush-rush and it was disheartening to realize what we had to look forward to. At approximately 0300 hours on Christmas Day, a train full of wounded German soldiers arrived and unloaded.

"While we were together in the station, all of the wounded personnel, regardless of country and status, started singing Christmas carols — the first one was "Silent Night," then "Joy to the World." It was a touching moment. Here we were, POWs who were supposed to be enemies, many of us suffering pain. Yet everyone had the Christmas spirit and sang these wonderful songs together.

"Every Christmas season since then, whenever I hear the first singing of "Silent Night," I think back to that "most memorable" Christmas Day of 1944. I thank God I am still alive. I am sure that if it weren't for Christmas Day 1944, and the Christmas spirit, I might not have made it back as one of the few survivors of the Maelmedy Massacres."