Preserving the Prairie: Been there, didn't do that

Second of three parts

Studies on how to preserve the Rathdrum Prairie have sat untouched for decades, but a new proposal hopes to take action before it's too late.

Earlier this year, Kootenai County Community Development Director David Callahan discovered three boxes of files documenting several open space studies from the turn of the 21st century. In brief, Callahan said the files tracked an ongoing public outreach effort intended to "garner support for an open space program."

However, regional leaders didn't implement preservation measures listed in the studies due to lack of community support, funding and ability.

A new initiative pitched by Kootenai County Planning and Zoning Commissioner Wes Hanson last week aims to avoid the same outcome. The Press covered Hanson's request on Dec. 12.

PAST STUDIES

Between the late 1990s and early 2000s, three studies were taken up by leaders and citizens with a similar mission: protect the Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer and develop a green space plan for the prairie.

In June 1996, a 19-member advisory committee published a study that dissected the past, then-present, and future of the Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer. The aquifer was primarily managed by Panhandle Health District and Idaho Department of Environmental Quality.

The Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer formed during the last ice age and is the primary water source for more than 500,000 people in the Spokane and Kootenai County region today.

"The vulnerability of the resource was originally proven in the mid-1970s with detections of elevated nitrates down gradient of densely populated areas relying on septic systems for disposal of wastewater," the 1996 study says. "Recently, industrial solvents and pesticides have been found in public water supply wells. Despite many protection efforts, a few water supply wells were abandoned due to contamination."

In the 1970s, local jurisdictions received grants through the federal Clean Water Act to study management plans for the aquifer. The 1996 study said "hundreds of wells" were sampled across Kootenai and Spokane County.

"The results of a year of monitoring showed the water quality was still good, but definite trends of deterioration could be attributed to human activities on the ground surface above," the study says.

Three years later, an executive, steering and citizen advisory group took up the Rathdrum Prairie Project. In 2000, the group contracted with Consensus Planning, Inc. and Meckel Engineering & Surveying, Inc. to publish the "Rathdrum Prairie Implementation Strategy: Phase 1 Final Report."

The document was an extensive review of plans, policies and regulations conducted by consultants for each of the six jurisdictions within the prairie — Kootenai County, Coeur d'Alene, Rathdrum, Post Falls, Hauser, Hayden and the Panhandle Health District.

"Overall, the plans and policies are relatively sophisticated for small western towns," the study's conclusion states. "However, there is a need to gear them toward common goals for the future of the Prairie."

Comments attached in a series of public meetings two decades ago echoed the worries of today:

"Challenge is to preserve what we have."

"If Prairie develops with 100,000 population, affordable housing goes away."

"Farmers have a right to farm. They were here before all the houses."

"Looking out over the Prairie adds to the quality of life."

The three underlying premises for the strategy, which the document attributes to any future initiative affecting the Rathdrum Prairie, were:

• Protection of the Rathdrum Aquifer

• Respect for private property rights

• Recognition that growth in the area is inevitable

"While growth is inevitable, it can be managed in such a way that the aquifer is protected along with the property rights of landowners in the area," the 2000 study states.

The study evaluated then-existing conditions for aesthetic quality, topography, geology, transportation corridors, development character and stormwater management. Within them, writers of the project frequently paint a picture that longtime Kootenai County residents know all too well:

"There is tremendous natural beauty in this area, which is being lost to strip commercial development along highways, checkerboarding of the Prairie, and the visual clutter of signage and utility lines."

Even in 2000, the planners were finding inconsistencies and "issues" in the land use and development on the prairie. Notably, the study cited "hodgepodge," "haphazard" and "proliferation of scattered" land use and housing developments across the prairie.

"Proliferation of piecemeal development undermines public goals of doing what is best for the prairie as a region," the 2000 study says. "Few opportunities for innovative development will occur without a regional approach and performance standards so business as usual will prevail."

The study claims that part of the issue is the 1978 PHD 5-acre rule aimed to disperse septic tanks and protect the aquifer. The study writers called the practice "well-intentioned," but they believed it to have "created a large lot growth pattern" that "carves up open space."

While the 2000 study was ongoing, the Idaho Legislature added I.C. 67-6515A on the "transfer of development rights." That law allowed any city or county to authorize landowners to voluntarily transfer their property's development rights to "preserve open space, protect wildlife habitat and critical areas, (and) enhance and maintain the rural character of lands." Once the transfer of rights was complete, it would restrict development on the property "in perpetuity."

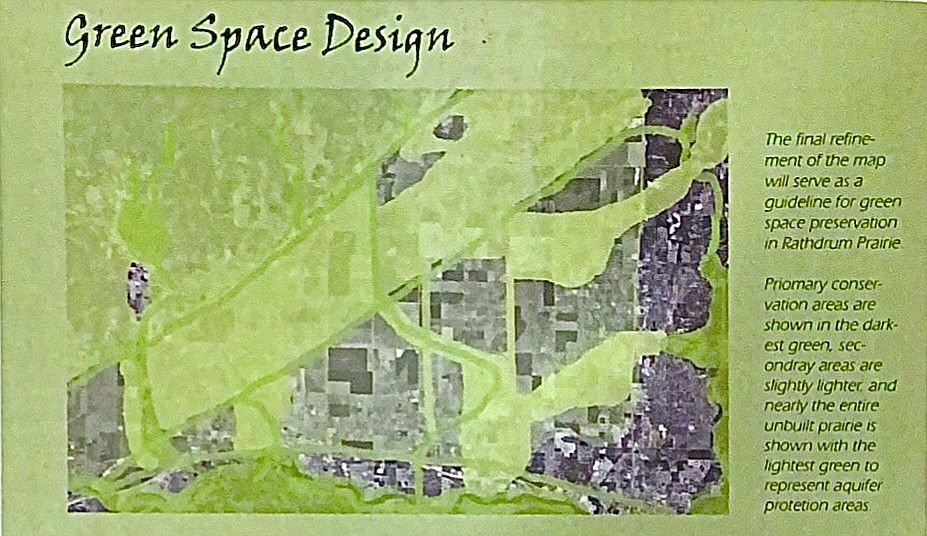

In 2002 a new plan emerged to protect prairie green space. According to the document, Kootenai County's growth rate was in the top 1% nationally based on U.S. Census Bureau data, which was causing "rapid development and threatening the natural qualities of the prairie."

Between 1990 and 2000, the county grew from about 70,000 residents to an estimated 108,000. The Census Bureau reports Kootenai County is home to 171,362 residents now.

Through a series of public workshops, participants produced maps that sectioned Kootenai County land into Cultural, Ecological, Development, Agricultural, and Recreations (CEDAR) categories.

But, as it said in the 2002 document, "the best-laid plans are of no consequence unless they are implemented."

"Creating a plan is often the biggest but the simplest step," it said. "Often the greater challenge comes next, getting people to overcome their hesitations and comfortable ways to put a plan into place."

The document emphasized the need for all local jurisdictions to implement green space measures. Otherwise, it said, "the entire prairie will suffer if even just one town is not on board."

Part 3 will be published Wednesday.