Vehicle fee: 'There's no plan B'

With 22 days until the Nov. 3 election — and ballots already being returned to the Kootenai County Elections Department — residents are making their decisions on a $50 local option vehicle registration fee for infrastructure improvements.

That begs the question: What if it fails?

Of the $476 million the State of Idaho raised through Highway Users Revenue in 2019, only $13 million came back to Kootenai County. Our 2.7% sliver of the revenue pie is then split between four highway districts and 13 cities. Highway districts split the money evenly, Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization executive director Glenn Miles said, but cities are portioned out by population size.

In 2018, the city of Dalton Gardens received about $1 million to service its roads. By comparison, the city of Coeur d'Alene saw over $20 million. This may seem like a hefty sum, but considering roadway projects like the Government Way expansion several years ago from Hanley to Prairie Avenue cost $10 million, that money does not go a long way.

According to Miles, 98.5% of the local option vehicle registration fee revenue will return to Kootenai County projects, with the remaining 1.5% being retained by the Idaho Department of Revenue for administrative purposes. If passed, initial estimates for first-year revenue returns on the fee are around $7.3 million based on 2019 vehicle data.

"Assuming a 2% annual increase in vehicles between 2021 and 2041, that amount is expected to rise approximately to $11.4 million annually," KMPO data said. "This estimate should provide over $200 million toward implementing the 12 designated projects."

One of the projects, a two-year $21 million underpass for the Union Pacific and BNSF Railroad lines in Athol, has been talked about by local jurisdictions since 1966, Miles said. Despite 54 years of interest, nothing has been done to move the plan forward because of a lack of funding.

Initially, the project was part of the "Bridging the Valley" plan designed by KMPO in 2005 to separate vehicle and train traffic in the 42-mile corridor between Spokane and Athol. The plan's purpose was to promote economic growth, traffic mobility and safety while providing train whistle noise abatement, Miles said. To date, no substantial funding was collected to complete the goals.

"It's a safety issue as the number of cars and trains crossing the tracks continues to grow," Miles said. "But there is also the amount of delay and backup caused when trains are going through."

The corridor, which passes right through Athol by the city hall building, is frequently used by residents and recreational drivers going to the mountains, Silverwood Theme Park, and Spirit Lake. Recently BNSF has been laying another railroad track to double the number of trains traveling at one time, which Miles said will dramatically increase wait times at crossings and safety concerns.

"I've seen people trying to race down the highway because they see a train and don't wait to wait for it, which can lead to a serious accident," Miles said. "Those trains are over 7,000 feet long, they're going 69 miles an hour, and they can't just stop if someone is in front of them. The train always wins."

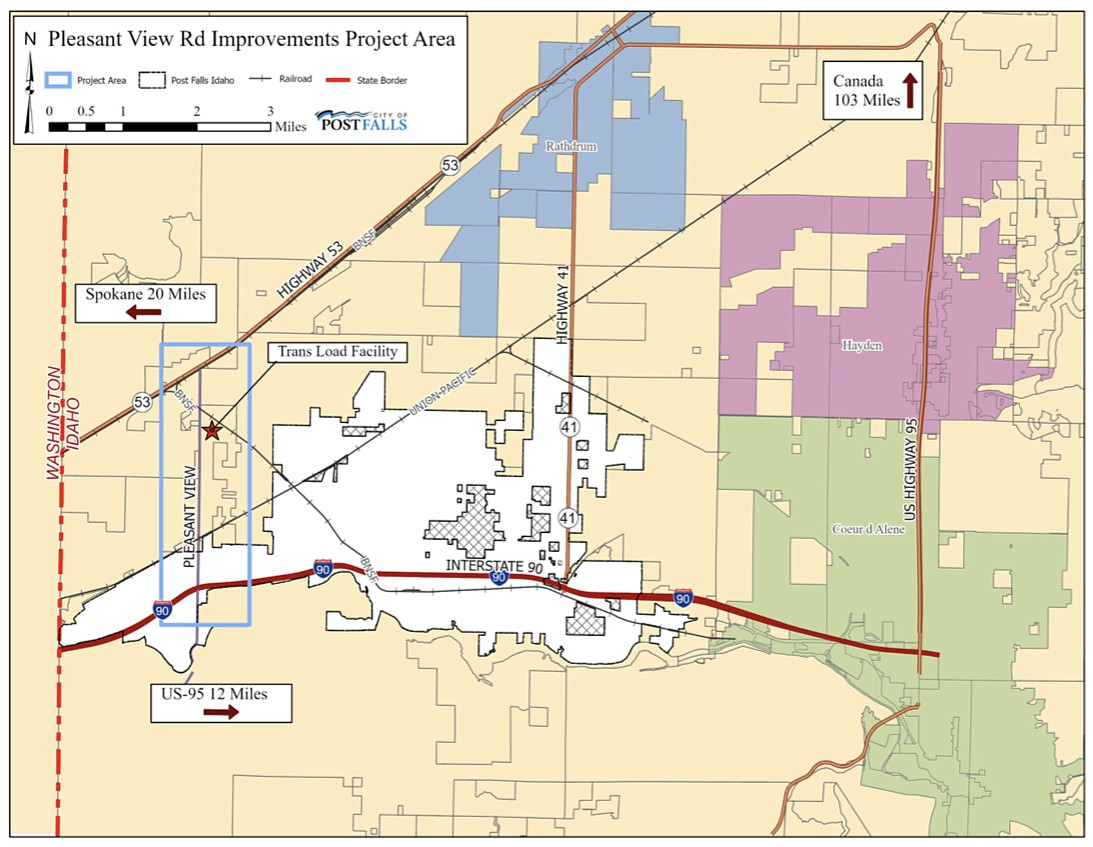

In Post Falls, a two-year, $15 million project would expand Pleasant View Road from Seltice Way to Highway 53 to five lanes. As a primary connector between I-90 and Highway 53, Post Falls community development director Bob Seale said Pleasant View Road would most likely become a direct route for commuters.

"This is the corridor that we are looking to annex property on and develop an urban renewal district," Seale said. "We envision it becoming potentially the next light industrial, commercial corridor in the city."

Seale said Post Falls is expecting a strong return on investment with not only new developments but an increased tax base and job availability. Right now, he said, Pleasant View Road is only two lanes and is seeing a rising level of commercial and residential traffic that has made the corridor more challenging to handle.

"Improving it would help that traffic which now is at risk for a higher likelihood of potential accidents," Seale said. "We do think that it's extremely important to have the improvement made along that road."

In the vehicle fee proposal, which would hike motorcycle fees by $25 annually, KMPO also has a two-year plan to expand Atlas Road in Coeur d'Alene from Seltice Way to Hanley Avenue. A little less expensive than Pleasant View, the $8 million Atlas expansion would jump to two lanes and a middle turn divider.

"It was an old country road that came into the city through annexation, so it was never built to city standards," Coeur d'Alene city engineer Chris Bosley said. "The southern portion of it has become a constant maintenance issue that we put a lot of money and time into each year."

Some of the challenges Bosley said the city have faced with Atlas are its stormwater runoff, lack of trails and bikeways, deteriorating pavement, and lack of a left turn lane. While Coeur d'Alene had applied for a grant to take care of some of these issues with KMPO, it came second to the Post Falls Prairie Avenue updates.

"Besides a federal or state level grant that might come along, our best bet to fund the project would be to use local impact fees, but those are divided between other projects as well," Bosley said. "There are a lot of comments from the public that the road is falling apart, but we just don't have enough money to fix it."

Obtaining a federal or state grant is not all that easy, but it is crucial for KMPO to complete its 12 projects. Through the income of the $50 fee on top of current registration fees, Miles said the county will take out a loan and leverage its combined sum to apply for competitive federal grants.

Federal participation in transportation grant funding is usually capped at 60%, Miles said, but to qualify, KMPO would have to demonstrate a local and state interest by fronting 40% of project costs. If the fee doesn't pass, however, Kootenai County will get nothing. No loan, no grant money, and none of the 12 projects.

"These won't happen, there is no plan B," Miles said. "There are no other local options. There is no revenue stream to go after them. We either play smart, or we don't play."

The earliest the projects would start to be planned without the fee would be 2026 or 2027, Miles said, and they would take drastically longer. Updates to Highway 41 could take 15 years; costs for Highway 53 projects could jump to $50 million.

"People either have to value what the transportation system does for them enough to keep it going, or they have to live with their choice of more congestion and more frustration," Miles said. "I respect the voters' right to decide. If they say no, then we have to respect what they chose."