MOMENTS, MEMORIES and MADNESS with STEVE CAMERON: You want to be close to the action, but it isn't quite what you think

It’s a different world down there.

When you watch the Seahawks on TV, analysts like Troy Aikman on FOX make the game sound like a chess match.

They show replays and point out how a safety moved to cover the tight end, thus opening space for the slot receiver.

And so on.

There’s no way you can tell, nor can they really explain, that all the movement and interplay being described is not exactly a video game.

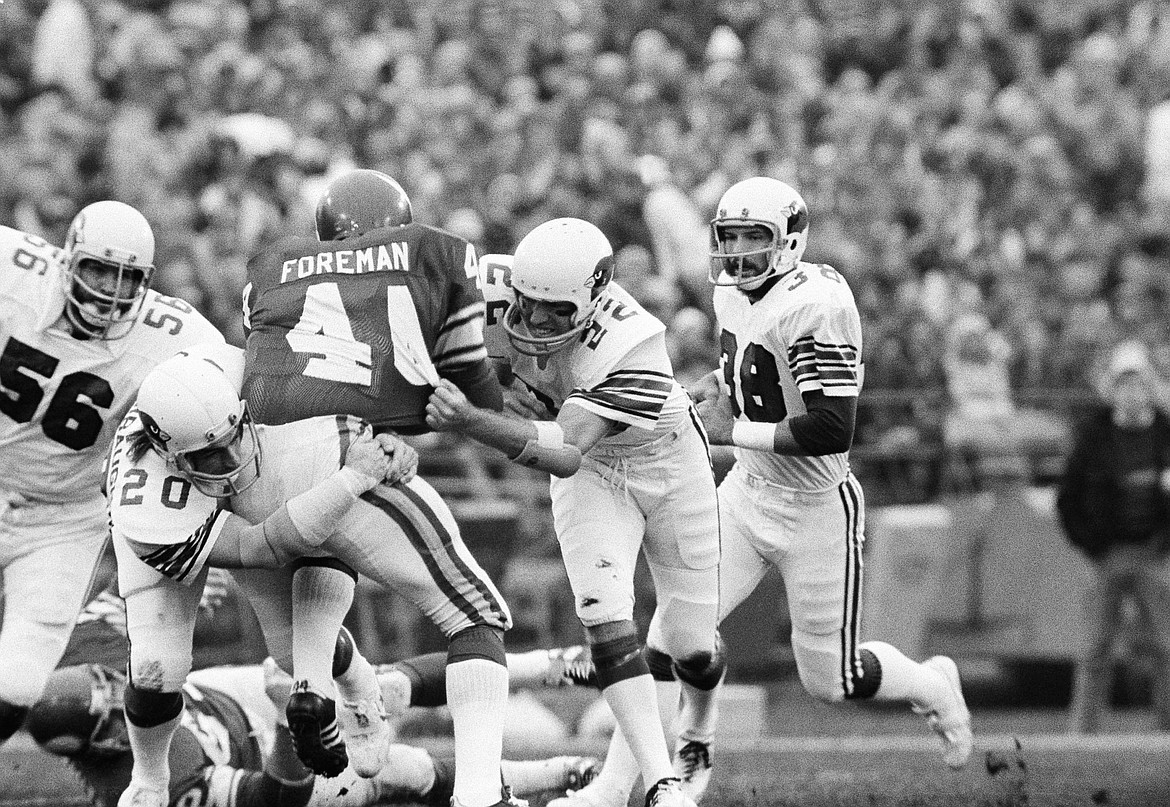

On the field itself, in case you’ve never been there, all those Xs and Os are actually huge human beings engaged in serious violence.

Utter, brutal, sometimes terrifying violence.

And the sidelines, where you imagine savvy coaches are preparing mastermind moves for the next series?

Hell, it’s chaos.

Screaming, bleeding, players banging helmets to encourage each other toward more effective mayhem when they get back to it.

I’ve often told friends that if they’ve never stood and looked down the line of scrimmage at an NFL game, it might frighten them to the point of fleeing on the spot.

IN THIS bizarre season of the coronavirus, reporters cannot interact directly with athletes.

We hear from the coach and two or three players via a Zoom connection.

For a good chunk of my career, however, there was no virus and there weren’t so many well-designed venues.

In the most modern stadiums these days, there is an elevator that whisks media members from the press box to an interview area (and the locker rooms).

But before these nifty elevators, reporters would be escorted to the actual playing field, generally with a few minutes left in the fourth quarter.

The idea was to allow us reasonably quick access to coaches and players without having to battle and jostle mobs of fans on their way out of the place.

So…

I’ve spent quite a bit of time on NFL sidelines while massive men crashed into each other at frightening speeds — and as a bonus, I’ve heard plenty of the trash talk that you don’t get on a telecast.

Let me note here that the first thing you learn near the field is that everyone — players, coaches, officials, assorted staffers — seems like they’ve gone insane.

Maybe there’s order to what’s going on (what Aikman and Co. are explaining to viewers) but when you get up close, it feels like complete madness.

I THINK my favorite description of pro football — on the field, not your TV set — came from Lynn Dickey.

Lynn played quarterback at Kansas State, then had a long career that culminated with years of sustained excellence in Green Bay.

When Brett Favre set most of the Packers’ passing records (most now possessed by Aaron Rodgers), Brett was jumping past Lynn Dickey in the Green Bay record books.

Dickey is blunt in his assessment of the sport in which he had so much success.

He thinks everyone is nuts to play it, and knows he’ll be crippled or worse when it’s over.

Dickey laughed when I asked him once if players sometimes wanted a little chemical assistance to go knock heads.

“Of course, players will take some kind of drug or stimulant,” he said, chuckling. “Yeah, of course. “I mean, what sane and sober person would go out there and get killed without some mind-altering substance.”

Dickey used an experience from just one normal practice day to explain the full terrors of pro football.

“It was a drill where the first group would run a play, or the start of the play.

“Then another group would get a rep, and if you were in the first group, you’d stand a few yards back while a coach gave you the next play.

“I honestly didn’t realize how frightening the sport I was playing really was until I was standing there one day, and when the second group ran their play, the ground actually shook when guys collided at the line of scrimmage.

“It was like an earthquake, and I remember thinking that I picked a hell of a way to make a living.”

Dickey, by the way, suffered a badly broken leg early in his career.

“It turned out to be a blessing,” he said, “because for years afterward the trainers and doctors gave me some really magic pain pills.

“It was a lot easier to trot out there in kind of a fog. It was a great feeling, because you didn’t have to think that you might get your brain scrambled on the next play.”

FOR THE record, I actually got injured in an NFL game.

It happened in the old stadium in Cleveland, and we had to get on the field pretty early, because the press box was actually surrounded by regular seats, and you had to fight your way through a few thousand screaming fans to get out of there.

I was covering the Kansas City Chiefs at the time, and they were beating the tar out of the Browns.

So. there wasn’t much reason to pay close attention to the action as the final couple of minutes wound down.

In that span, though, the Chiefs scored again.

When they kicked off, Cleveland’s return man headed up the sideline where I was talking with some other media types.

All of a sudden, a Kansas City safety named Mike Sensibaugh came flying in our direction after missing a tackle.

Before I could even move, Sensibaugh had hit the ground and rolled hard into my right leg.

I flew butt over tea kettle from the impact, and then discovered that I had a badly sprained ankle.

We still had to walk to the locker rooms, then around the giant stadium to the PR director’s car for a ride to the airport.

I’m not sure I’ve ever felt more pain in my life — all because I was daydreaming on an NFL sideline, and the violence spilled over in my direction.

Even now, when I watch a game on TV and a couple of players go flying out of bounds at top speed…

It makes me wince.

Trust me when I say that you’re not getting the real thing on television.

And that’s just as well.

Email: scameron@cdapress.com

Steve Cameron’s “Cheap Seats” columns appear in The Press on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. “Moments, Memories and Madness,” his reminiscences from several decades as a sports journalist, runs each Sunday.

Steve also writes Zags Tracker, a commentary on Gonzaga basketball that’s published each Tuesday.