The FLAGS of their FATHERS

St. Maries Legion reunites WWII battle flag with the Japanese family of fallen officer

When Mitaro Horiya died near the Goto Islands off the southwest coast of Japan in 1944, he became one of two million Japanese soldiers to die in World War II.

Horiya was a 27-year-old logistics officer aboard a supply ship heading to battle when his Japanese carrier was struck by an American torpedo a year before the Japanese surrender.

He left behind a wife and a 1-year-old son.

Horiya’s death in 1944 is among millions of forgotten footnotes from a war that is quickly being relegated to written history.

But earlier this year, Jim Shubert of St. Maries was reunited with the memory of Horiya’s death as he rummaged through a storage shed of the Lloyd G. McCarter American Legion Post 25. Inside, he found a Japanese battlefield flag that had been donated as memorabilia, and he returned it to its rightful owner.

That small act brought history to life last week as the son of the man who carried the flag into battle almost 80 years ago contacted Shubert and the Legion post to say thank you.

“I don’t really know how this flag was discovered under these circumstances,” Noboru Horiya wrote in a letter from Japan. “I sincerely appreciate that the flag carried by a fallen enemy soldier was carefully kept by some opponent during war at the risk of his life in order to finally return it to the war-bereaved family.”

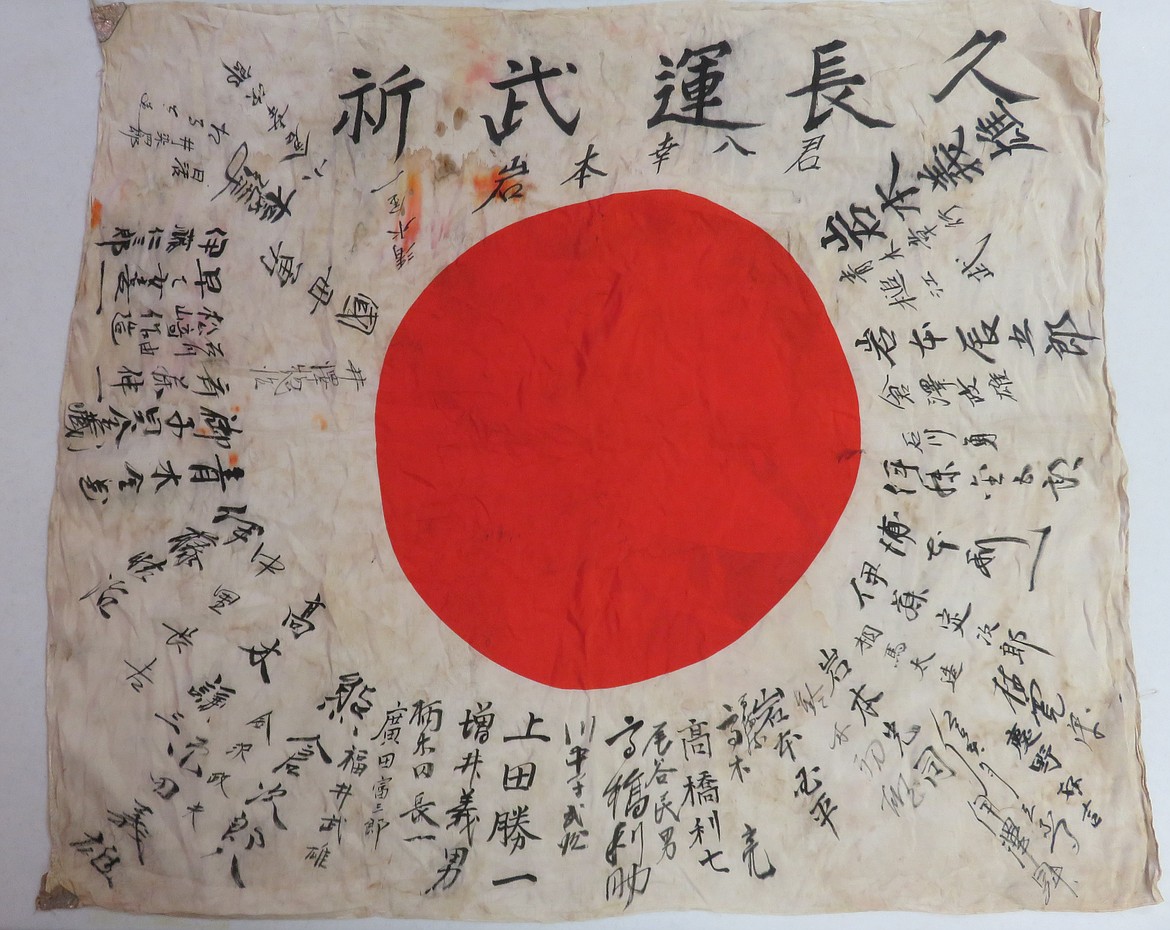

Standing in the legion post storage shed several months ago, Shubert, a Navy veteran, former fire chief and the commander of the St. Maries post, was struck by an impulse after unfurling the flag with its red, rising sun symbol. He considered the handwriting and the blood on a corner.

“This feeling came over me,” Shubert said. “These flags don’t belong to us.”

Having learned enough about the Japanese language and culture during his time in the Navy, Shubert knew that the flags were “good luck flags” that carried penned signatures and messages from service members’ family, friends and mentors. The writings fanned out from the red center symbol like rays from the sun.

Japanese soldiers, airmen and sailors carried the momentos, called yosegaki hinomaru, into battle in an effort to be shielded by their tidings for victory, safety, and good luck.

Like letters found on a battlefield, the flags, Shubert surmised, should be returned to Japan.

“These belong in Japan with the families of the deceased veterans,” he said.

Shubert contacted the Obon Society, an Oregon group dedicated to returning personal artifacts lost during war. Using a sophisticated network to find families, the Obon group last year returned almost 100 items to the island nation to be reunited with relatives.

Shubert, who did not know Horiya or his family, packaged the five flags the Legion post had accepted from the family of a St. Maries veteran, and sent them to Oregon.

The flag’s journey to St. Maries had taken a circuitous route since 1944. The five flags that the post sent to Oregon had gone through New Guinea and eventually landed on the East Coast.

John A. Koelbel, an Army veteran of the Pacific Theater of World War II, kept them in a sack in the trunk of his 1937 Plymouth. Koelbel lived in Maryland, and his son, John D. Koelbel, an Army veteran who lived in St. Maries, had the car shipped west when his father died several years ago. The flags were still in the trunk.

When John D. Koelbel, a paratrooper, pilot and member of the St. Maries Legion post, died three years ago, his wife, Carol, donated the flags.

She didn’t know much about their history.

“His dad never spoke about them,” Koelbel said. “They were all kept in a woolen sack.”

When she read the letter of thanks from Horiya, it brought tears to her eyes.

“It has a lot of significance in that culture,” said Koelbel, whose dad served in Korea. “This has been 80 years ago. They still have the love and respect for the elderly.”

Shubert said the Legion keeps an empty chair at its ceremonies, meant to honor POWs and soldiers missing in action. The return of the flags to Japan, he said, is similar to returning the remains of an MIA service member.

Shubert said he felt kinship with Horiya because as a crewmember aboard the USS Ajax between 1966 and 1969, “We sailed through the same waters many times.”

In his letter to the St. Maries Legion, Horiya, 77, said he and his wife made commemorative trips to the U.S. in honor of his father. Four years ago they climbed a mountain on the Goto Islands — the islands share the name with a Japanese naval commander — to bring back sand for his father’s grave.

“I put the sand in a glass bottle and offered it to my father’s altar to pray for him every day,” Horiya wrote.

He was surprised at the flag’s impeccable condition.

“I promise I will inherit this flag to future generations as a keepsake of my father…”

The Obon Society is still trying to find owners for three of the flags donated by the St. Maries Legion.