Immersed in history: Tattoo Museum, shop tells story of American ink

Jay Brown didn’t intend to become a historian, or curator.

The tattoo artist got into the business 34 years ago for the art – and a love of tattoos.

“The fact that your art work is ‘living’ was really alluring to me,” Brown said.

It didn’t hurt that the money was “really good” back then, either.

Not every artist wants to starve, as he once explained to his chagrined, artist grandmother.

Now the owner – and curator – of the Northwest Tattoo Museum, Brown is an expert on modern electric tattoo history.

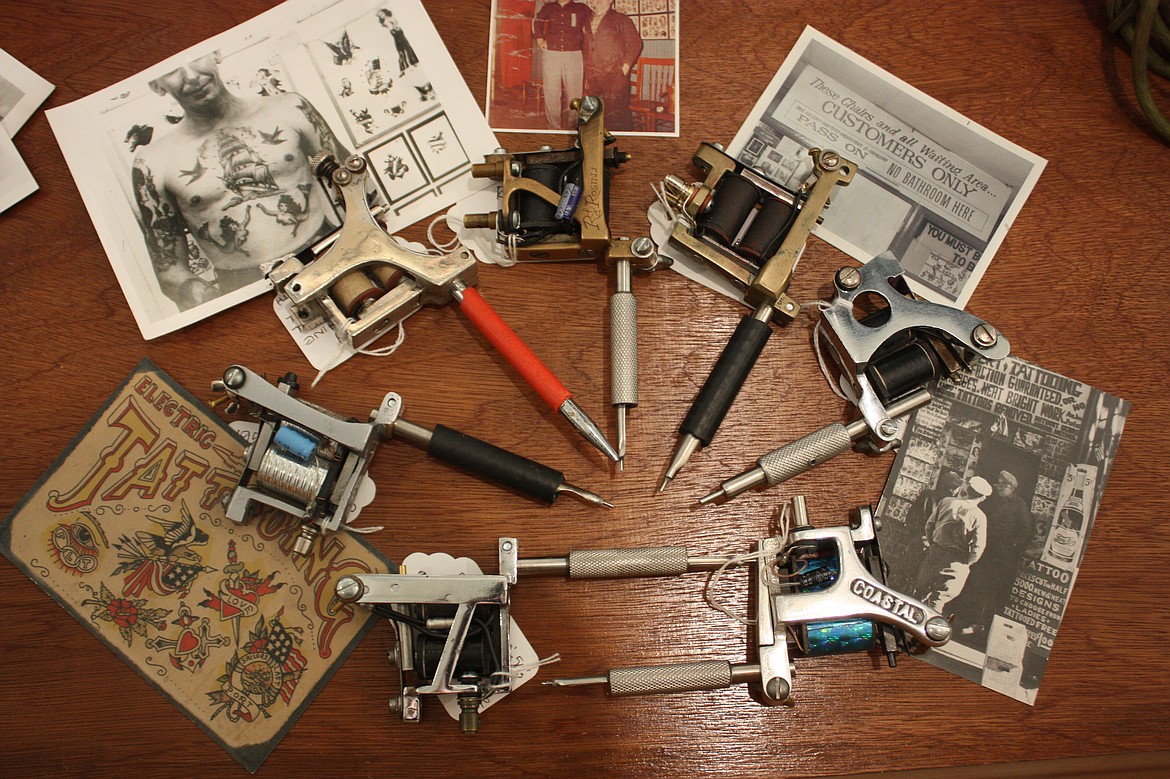

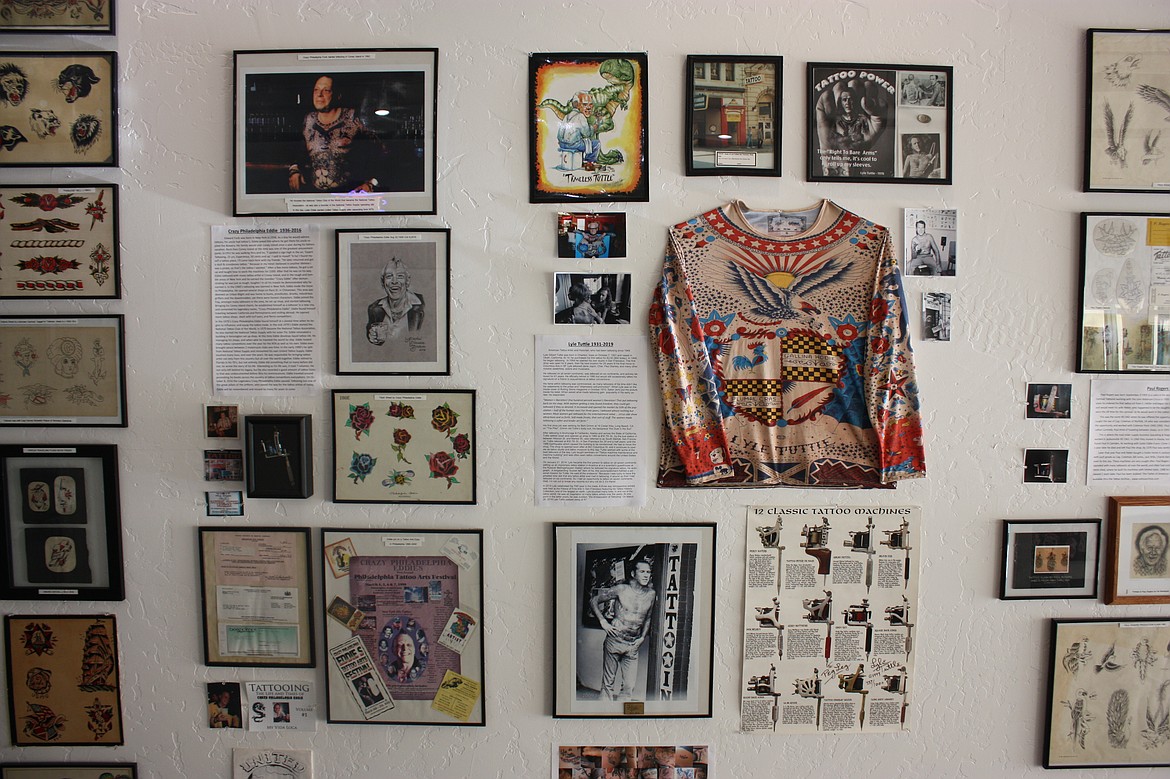

The museum, about to open in its new location on Government Way, features vintage “flash” or design sheets from artists, tattooing machines and other artifacts, as well as historical photos and documents.

It also functions as an active tattoo shop, where Brown and other artists who rent the space can work their magic.

Richard Brockway, a tattooist of 25 years who has worked at Northwest Tattoo since last August, is happy to be there.

“I’m surrounded by my history every day,” Brockway said, “which is what attracted me to the profession in the first place.”

“It’s the culmination of my dreams with this whole tattoo shop project,” Brown said.

“I love tattooing so much – and the history of it.”

After moving to Coeur d’Alene from Moscow, Idaho in 2012, he opened the Northwest Tattoo Museum where the former Blue Rose Tattoo shop once stood on Fourth Street.

Seven years later, it has a new home at 2934 Government Way.

The museum is hoping to officially reopen as part of Gov. Brad Little’s second phase of reopening after COVID-19 business restrictions.

The timing of the move early this year meant Brown had more time to focus on displays as well as painting and building the working shop part of the museum.

It also means the brand new “wipable, disinfectable all the way around” area for active tattooing, with its hospital-grade white cabinets and artist stations eight feet apart, will be ready just in time for the shop to practice even stricter safety measures than normal.

“As professionals we hold ourselves up to a higher standard,” Brockway said.

“We do things in such a way that our customers are protected as well as ourselves.”

The museum first came about by accident about 10 years ago, after he began collecting tattoo-related artifacts and old designs.

“It was more of a personal collection,” Brown said. “It just became a passion.”

Ultimately, he had the idea to turn the collection into a museum, rather than leave it in drawers.

“That seems like a waste to me.”

Much of the objects were purchased or traded for by Brown himself. He also makes tattoo machines, which he has sometimes traded for additions to the museum.

The active tattoo shop within the museum functions like a “working exhibit,” Brown said.

“You can’t get tattooed there and not be immersed in the museum. It’s all around you.”

“It reminds me of the tattoo shops – or how I remember the tattoo shops used to be,” Brockway said, “[with] lots of vintage designs everywhere.”

Admission to the museum is free, because as Brown says, “No museum makes it off the price of admission.”

While some visitors make donations, the tattooist jokes this is largely to “buy the crew lunch from time to time.”

The shop funds the museum instead, while drawing attention to it.

“It supports the museum. It keeps it going,” Brown said.

“So I have a space to be and the museum has a place to be.”

With almost 1,600 square feet, Brown is excited to have more room to “immerse” visitors and customers with more displays.

“It’s really gonna blow people away.”

Much of tattoo history is based on an oral tradition, and Brown says relatively few books have been written on the subject until fairly recently, when older “greats” began writing their stories down.

“Tattoo history is vague in some points,” Brown said. “It’s one story told to another person. Others passed it on.”

Fittingly, Brown furthers understanding of that history through tours, a more formal footstep in the oral tradition. Knowledgeable about his subject, Brown details how much of the tattoo world was once a “rough and tumble” scene, when shops existed largely in back alleys or underground and harsh turf rivalries could brew trouble.

“I enjoy watching him give his tours,” Brockway said.

“And he gives a thorough tour. He walks you through each person’s history and his experiences with them as well.”

To hear Brown tell it, tattoo history is as colorful as the art form – and Brown’s own history is equally detailed.

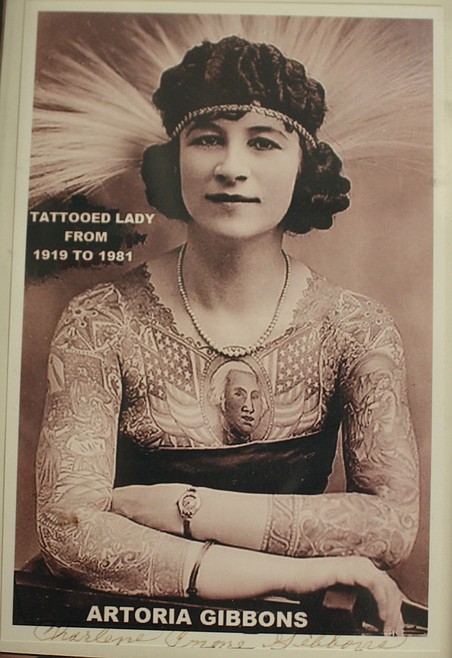

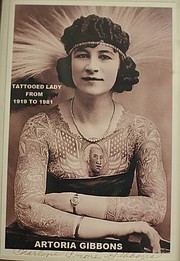

Some tattoo artists had their start or otherwise worked as part of traveling circus’ crews. Tattooed men and women were not always a sideshow act; some were also active artists before, during and perhaps after their circus careers.

Even Brown once ran away to join the circus – and followed it with a more modern Grateful Dead Tour in his early career. Where some Deadheads sold burgers or merchandise at shows, Brown sold his ink.

But his connection to history extends further. In addition to his steady collecting and researching of the past, he befriended many of the great masters of the previous generations.

“He was friends with some of the greats,” Brockway said.

The founder of the National Tattoo Supply and the former National Tattoo Club of the World, called Crazy Philadelphia Eddie Funk, is among Brown’s acquaintances.

One great father, RJ Rossini, is affectionately referred to as “the old man”.

“We had an adopted dad-adopted son relationship.”

The active tattooing section of the museum is named “Rossini and Brown’s” in his honor.

“I wanted him to have first billing. I spent over a decade of life with him,” Brown said. These relationships add a deeper meaning to the museum. For fellow friend and artist Brockway, it provides a closer connection to recent history by association.

“I never had the opportunity to meet those people,” Brockway said “It’s through [Jay] I kind of get an idea of what they were like. That’s pretty amazing.”

Brown joked that there were some stories of these “fathers” of tattooing he wouldn’t tell on the record. But he did tell that some of these greats once snuck into a bar after hours to serve themselves – and tipped hundred dollar bills for the bartender who would come back the next day.

Brown also told how his friend Crazy Philadelphia Eddie Funk, the “Godfather of Tattooing” and author of a seven-volume memoirs of his “vida loca” as a tattooist, would call him at three in the morning (the author lived on the east coast) to confirm details for his memoirs.

“It’s been an interesting life tattooing,” Brown said.

But the magic isn’t all in the knowledge of the profession’s past.

“Working in a museum, it’s like the ghosts of tattooers past are alive and well in their personal items and actual photos. And [they’re] even like remains,” Brockway said.

“They definitely retain what we call the magic — the hands that touched them, the hands that used them…as well as the hands that painted them.”

The space is important for Brown, as well.

“It gives the tradition the proper respect. It enlightens people a little bit more.”

--------INSET----------

Local tattoo artist and modern tattoo historian Jay Brown is full of stories of the 20th century’s electric tattoo history – and of some of the greats who made it.

While a full account of the trade’s transition from a “rough and tumble” atmosphere to a widely accepted art form, can’t be easily summarized, here are a few highlights from the expert himself:

• In the Victorian era royalty – particularly well-to-do women – would often get back and arm tattoos that wouldn’t be seen under clothing.

• While tattooing has long been male-dominated, there have always been at least a few female artists.

• Some tattoo artists would travel with circuses and carnivals. Tattooed men and women were sometimes tattooists themselves, during or after their careers as sideshow acts.

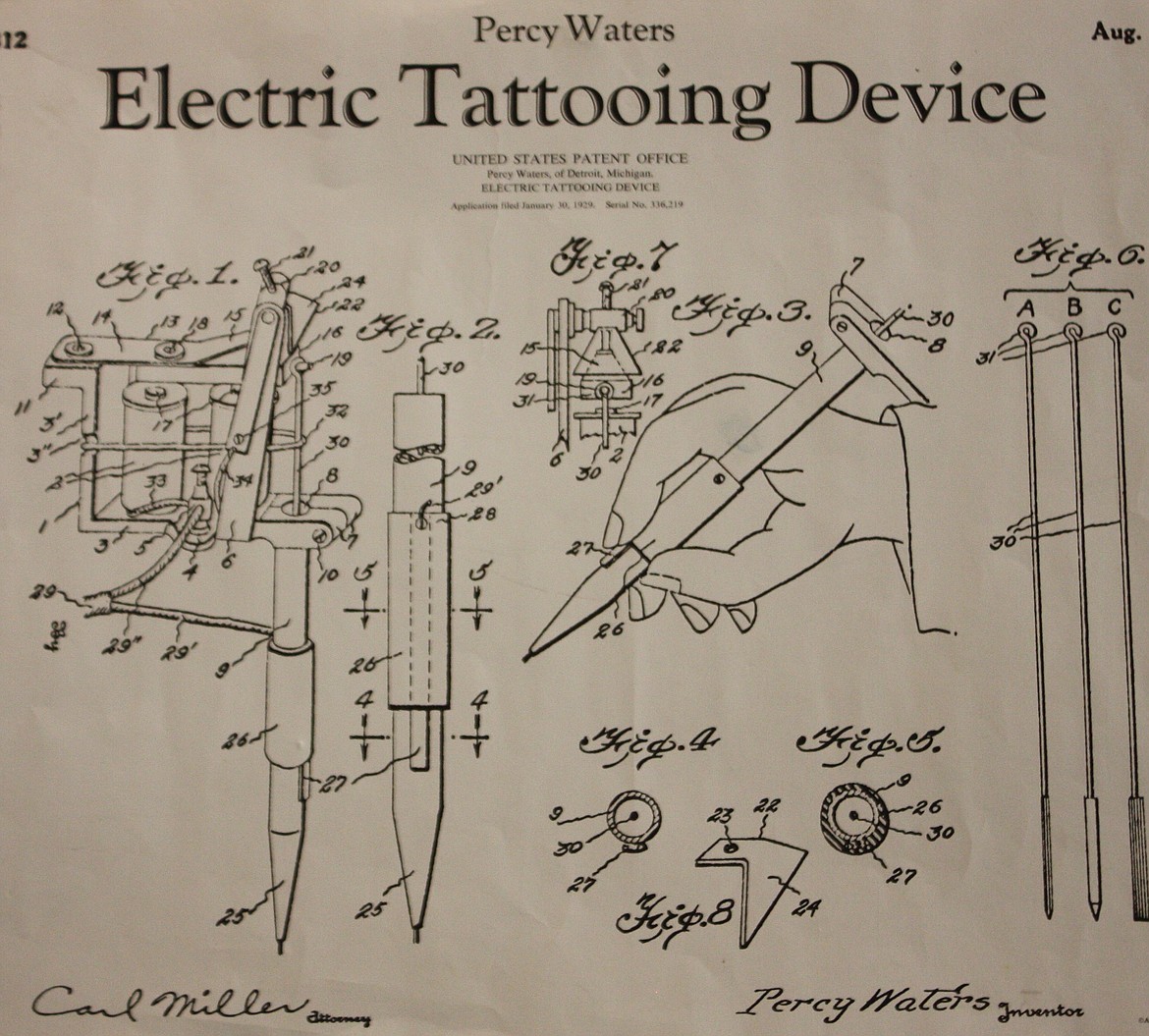

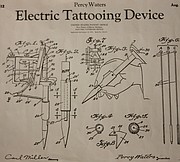

• The technologies that helped make the electric tattoo machine possible came from the inventions of the doorbell ringer and the Edison pen.

• Today, Brown finds more women than men are getting tattoos.

For more information visit the Northwest Tattoo Museum on Government Way or Gypsy-tattooer.com.