The story of yarn: From sheep to needle in the Northwest

Turns out, you can make yarn from a lot of different animals’ haircuts.

At Fibers First fiber processing mill in Post Falls, they’ve had the full spectrum of requests.

“(We do) mostly wool and alpaca, some llama. We’ve done buffalo, and there’s been a few other weird ones, too,” said Lowell Goodson who owns the mill with wife Karen.

“Well,” he added, “we’ve done dog, but we don’t really do that anymore, because it’s hard to get off the carders – off the machining.”

That’s just one of many things local knitters, weavers, crocheters, and spinners probably don’t know about where their yarn comes from.

But Katie Gilles would like to change that.

“I think it’s really important that people know where their yarn is coming from, and why that farmer picked those sheep and what’s (significant) about them,” said Gilles.

“There’s so many wools and every one is different and every one is good for different things.”

Gilles is passionate about connecting farmers and consumers. When she’s not busy raising her two sons, working as a nurse, or knitting, she develops her side project. Through Range Wool, she works to connect and educate either end of the production chain.

Most knitters know little about where their yarn comes from – even though textile production has a history here.

At the Range Wool website people can learn about the story of yarn, as well as connect with regional farmers and mills, and purchase locally grown yarn and roving – the strand of fibers from which yarn is made.

Her project takes its name from the wool grown on this side of the Rockies.

“So that kind of education, even to the knitter, as to why would I want a certain kind of wool and what would I use it for and how would I use it was also my idea with range wool.”

Gilles herself has learned much of the production process. The lifelong knitter learned to spin and even worked for Fibers First for about a year. She’s still learning about different yarn-related processes like dyeing or carding.

“Most of our wool production in the U.S. is sent overseas to be washed and turned into things and then shipped back here,” said Gilles.

“Most knitters don’t really know that and have no idea what goes into it.”

On the other hand, some farmers with animals such as sheep, alpaca or goats don’t know enough about the wool or yarn-production industry to become part of the chain.

“Most farmers are farmers, so they’re not marketers. They’re not sellers,” said Gilles.

“So I think it’s also an education to the farmers: what you can turn into the yarn or roving and what you’re looking for.”

The story of yarn from a sheep goes something like this:

First, sheep are sheared annually by a professional shearer to make sure the fleece comes off in one piece at a certain length.

“The wool has to be at least three inches long and not longer than seven, or we have to cut it,” said Goodson. “If it’s too short it won’t go through my machines.”

Next, the fleece is “skirted.” Any matted pieces, bits of poop or other undesirable additions that might be stuck are removed. Goodson says pieces of straw or fine hay have to be removed by hand.

He said washing the fleece can take about a week, because it must be washed multiple times and dried.

“You can’t agitate the fleece or it felts, so…it comes in and soaks. But the water’s got to be pretty hot, like 160 degrees. You have to wear rubber gloves so you don’t burn your hand.”

“You take it out before the water cools, so that lanolin that’s all over the wool [and] that makes it softer a little bit doesn’t collect back onto it,” said Gilles.

“Because if you have too much lanolin it will clog either your spinning wheel or more likely the equipment at the mill,” she added.

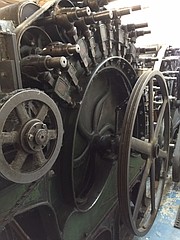

Finally, the cleaned and dried fleece gets carded and combed. The picker machine puts the wool fibers in a single direction “rather than just however it came off the sheep,” says Gilles. In the pin drafter, the fleece comes out a couple inches wide and “swirls just like an ice cream maker” into a barrel.

“It goes through that about three times and then it goes into the spinner and comes out as yarn – hopefully good yarn,” said Goodson.

Goodson took over the process from his wife Karen (who had over 25 years of experience in the fiber industry), who is allergic to the wool she used to breathe in all day. He’s learned the machinery and the process – but he’s not much help with spinning.

“I’m red-green colorblind, so the colors kind of look the same to me. They don’t let me sort the fiber,” he laughed.

Fibers First Mill produces either yarn or roving from fleeces, to-order.

“We’re actually a service industry,” said Goodson. “Basically, the thing that we do is people bring their wool in and they get their wool back.”

He says the whole process takes about a week and a half – but much of the year demand is so high it may take up to six months to process a request.

Most of the fiber comes from smaller farms in Washington and North Idaho.

“It’s kind of a local craft and so, the other thing is it’s kind of a relaxing thing, I think, for the spinners.”

Fibers First also processes smaller amounts of fiber than other mills across the country will, says Gilles, making it easier for regional farms to get products from the smaller flocks.

“Having the yarn mill in this area is such a gift.”

Hopefully that local tradition can continue.

“The wool industry is just kind of dying, but we really need it because of how important it is to the U.S. economy,” said Gilles.

“I think that the mills, and the small mills, independent mills in this country are dying. [Practically] no one is left who knows how to do this, so we’re losing these experts.”

However, the popularity of spinning – turning roving into yarn – is rising. Goodson said since his wife started spinning the price of spinning wheels has gone up and the number of brands has grown from a handful to much more.

There are many spinners in the area.

Juaquetta Holcomb has been spinning, dyeing and selling her yarn at the Farmer’s Market since 2015.

“I buy from small farms, like wool and alpaca, so it’s all local fiber,” said Holcomb.

“This is a market, you know. We like to show our sources.”

No kidding. She even knows the names of many of the animals who lent their coats. At her Wednesday stall in downtown Coeur d’Alene, she began to point to which color came from Snowflake the goat, Tracy the sheep, and Diamond the alpaca.

“Everything I do is from small farms in the area. It’s part of the fun of doing this.” Like Gilles, Holcomb says she also does “a lot educating people on wool, and the sources for it and how to care for it and how I make the yarn.”

Some of her dyes also come locally – from irises in her garden, dandelions or red onions.

Holcomb also explained some of the dyeing process, which she does in electric roasters, “like a turkey roaster,” in her studio.

“I purposely sort of usually do a bad dye job, because I don’t want it to be one flat, sterile color [and] look like a factory did it. I like the variation in it.”

She explained how one yarn had various shades of blue because of this imperfect process and pointed to “little purplies” that resulted from not washing the pan well enough.

Gilles agreed that this result was appealing.

“I think it’s pretty much the same advantage as to why you would buy carrots at the farmers market. It’s not going to be the prettiest yarn you’ve ever seen…[and] it’s not gonna be this uniform carrot that you’re used to seeing.

“But you love it because it’s got character and you know the person who grew it or made it. That’s why you buy a farm yarn.

“Whatever reason you choose to support your local farmer - it’s a good product. It’s the same reason you would choose to support a local fiber farmer.”

You can learn more about or take a virtual tour of the Fibers First Mill on their website Fibersfirst.weebly.com.