MOMENTS, MEMORIES and MADNESS with STEVE CAMERON: The night a hurdler’s world record was denied by an imaginary wind

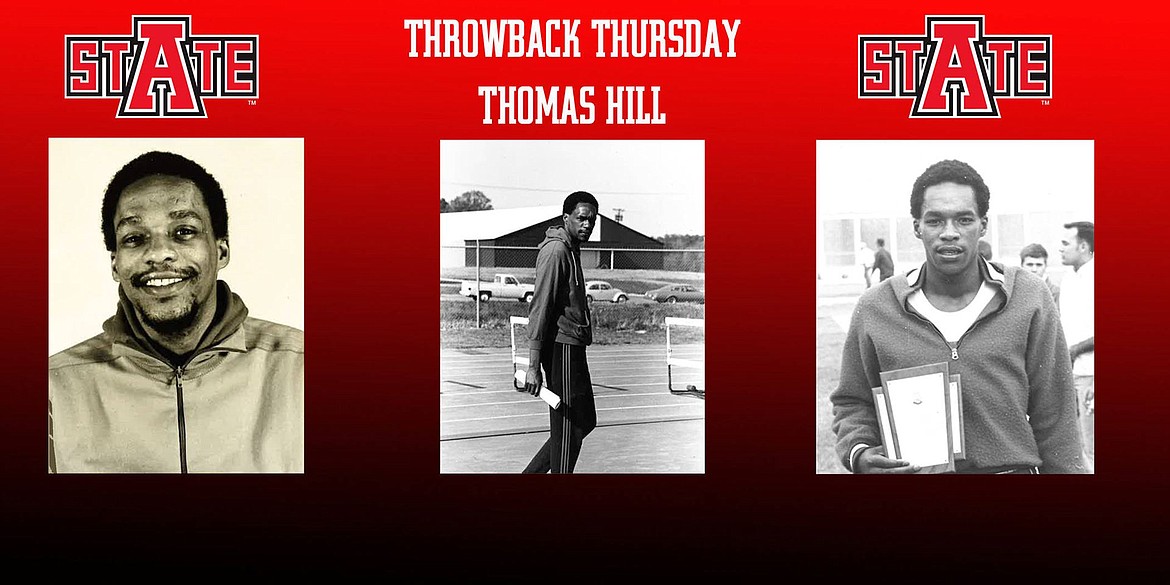

Perhaps you remember Thomas Hill.

You’ll be thinking of the Duke basketball player, the shooting guard who competed for the Blue Devils from 1989 to 1993 — back in the days when Coach K actually recruited kids to play four years.

Hill enjoyed two national championships at Duke, and you can still see him on TV, every time they show Christian Laettner’s iconic buzzer-beater against Kentucky in 1992.

Hill is the guy who bursts into tears of joy, so obviously out of his mind with surprise and excitement that you can’t forget the image.

But here’s the thing …

This story isn’t about THAT Thomas Hill.

Nope.

We’re going to talk about his dad.

I only saw Thomas Lionel Hill Sr. in person one time — but it involved one of the strangest and most unforgettable episodes of my journalism career.

I CAN’T even remember the reason that, as a young sports reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal, I somehow got assigned to cover the 1970 U.S. Track and Field Federation meet in Wichita.

Perhaps the University of Kansas had some star runners or throwers on show that year.

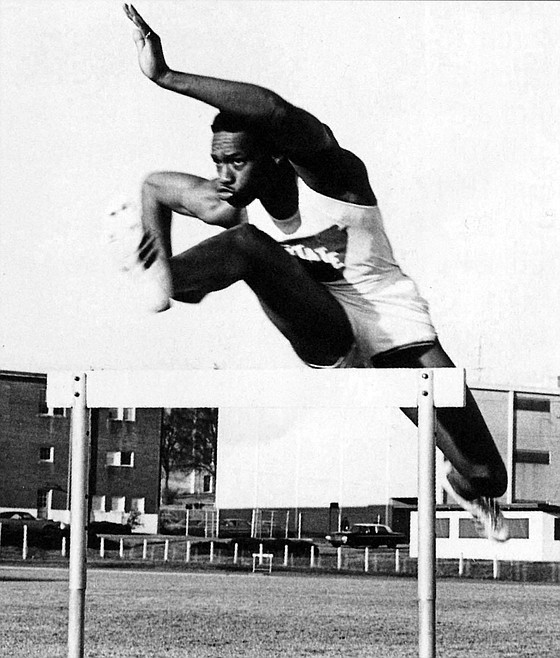

But the only person I’ll ever recall from that event was Thomas Hill — and how this soft-spoken, almost-too-polite hurdler from Arkansas State University got absolutely screwed out of a world record.

For context, you need to know that in 1970, the United States was still conducting track events in yards.

Not meters, which was the standard for the rest of the world.

So just to save you a trip to Google, I’ll report that 120 yards — as in the 120 high hurdles — is almost exactly 109.8 meters.

In other words, just barely, barely shorter than the normal international and Olympic distance for the 110-meter high hurdles.

THERE wasn’t any special reason why, when wandering around the infield at Cessna Stadium, I stopped to watch the 120-yard hurdles up close.

I have no idea why I was right at that spot.

However, I DO know that this young man that I had no idea even existed — Thomas Hill — won a 120 high hurdles preliminary race by the equivalent of a bus length.

He blew away the field.

I remember thinking: “Whoa! Was he running in a high school heat here, or what?”

These were supposed to be the best hurdlers in the country.

Then Hill’s time flashed up on the board beside the track: 13.1.

I was stunned.

Even without being a hurdles expert, I knew that the world record — yes, the WORLD record — was 13.2.

Without thinking, I hustled over to Hill (no one else in the place seemed to know what had just happened) and congratulated him on the record.

He was shy, slightly thunderstruck himself at his time, but he said: “I’ve really been running well, so I expected something pretty fast tonight.

“But a world record? No, I wasn’t thinking about that.”

NEITHER were meet officials, apparently.

After a bit of time, a couple of men in blazers (U.S. Track and Field execs, I guessed), came over to Hill and, standing right next to me, they told him his record wouldn’t count “because of the wind.”

Hill was completely baffled.

“There was almost no wind,” he said, “and what breeze I felt, we were running INTO it.”

They said sorry again, and walked off — leaving Hill completely confused.

Me, too.

Just like Hill, I had felt a very slight wind in the face of the runners. There was no way — no way at all — that his 13.1 was wind-aided.

Hill wasn’t the type of guy to make a fuss, but me?

Oh, yeah!

I finally hunted down the official in charge of the whole shooting match, and told him flat-out what I was sure he already knew.

Hill had gotten hosed.

After much hemming and hawing, he admitted that — even with about a hundred guys in blazers supposedly handling every event — nobody had turned on the wind gauge for a preliminary race in the 120 high hurdles.

Hill had definitely broken the record — but without an official wind clocking, it couldn’t be certified.

Morons!

BY THE time I got back to the hurdle prelims, they’d managed to get the wind gizmo working, and Hill promptly TIED the world record of 13.2 — despite running into a stiffer breeze than he’d encountered earlier.

After he’d warmed down, I gave him the news about the wind gauge malfunction (which actually was a human malfunction), and the fact that he had, indeed, run a legit 13.1.

Now, remember our conversion table.

That 120 yards is actually about 109.8 meters, so for the sake of argument, let’s add a tenth of a second to Hill’s time — thus accounting for that two-tenths of a meter.

In reality, it probably would still have been 13.1 with such a tiny difference, but we’ll err on the side of caution.

Using the IAAF’s electronically timed race standards, nobody ran faster than 13.2 at 110 meters until Renaldo Nehemiah ripped off a 13.16 in April of 1979.

That was almost a DECADE later than Hill’s gorgeous 13.1 at 120 yards in Wichita.

THAT evening has stuck in my mind forever.

You just don’t see world records broken by relatively unknown athletes every day.

And you certainly don’t see them erased from history — POOF! — simply because nobody in a blazer remembered to turn on the wind gauge.

Happily, Hill was not the sort of young man to be deterred by that sort of thing.

Eventually, his education earned him entrance into university administration, and by the time he became a vice president at Iowa State, he was Dr. Thomas Hill.

And by the way, his running wasn’t finished.

He came back from a serious injury to earn a bronze medal at the 1972 Olympics in Munich — overshadowed again by the tragic murder of the Israeli athletes at the hands of terrorists.

Hill also was able to enjoy his son’s stellar basketball career.

Looking back, Hill Senior probably doesn’t care all that much that he was officially credited with just tying the world record in the 120-yard hurdles instead of owning the record by himself.

But it bothered me.

Thomas Hill just seemed like SUCH a nice guy.

As for guys in blazers running huge events …

Enough said.

Email: scameron@cdapress.com

Steve Cameron’s “Cheap Seats” columns appear in The Press on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. “Moments, Memories and Madness,” his reminiscences from several decades as a sports journalist, runs each Sunday.

Steve also writes Zags Tracker, a commentary on Gonzaga basketball, once per month during the offseason.