The New Old Master: Artist keeps tradition alive

Story and photos by ELENA JOHNSON

Coeur Voice Contributor

Not every artist is keen to share their expertise, but Joe Kronenberg is not every artist.

Maybe it’s a natural side effect of being a Western artist.

“We’re very blessed in the western art genre to have everybody cheering for you and willing to share, he said.

“They’re the most giving people.”

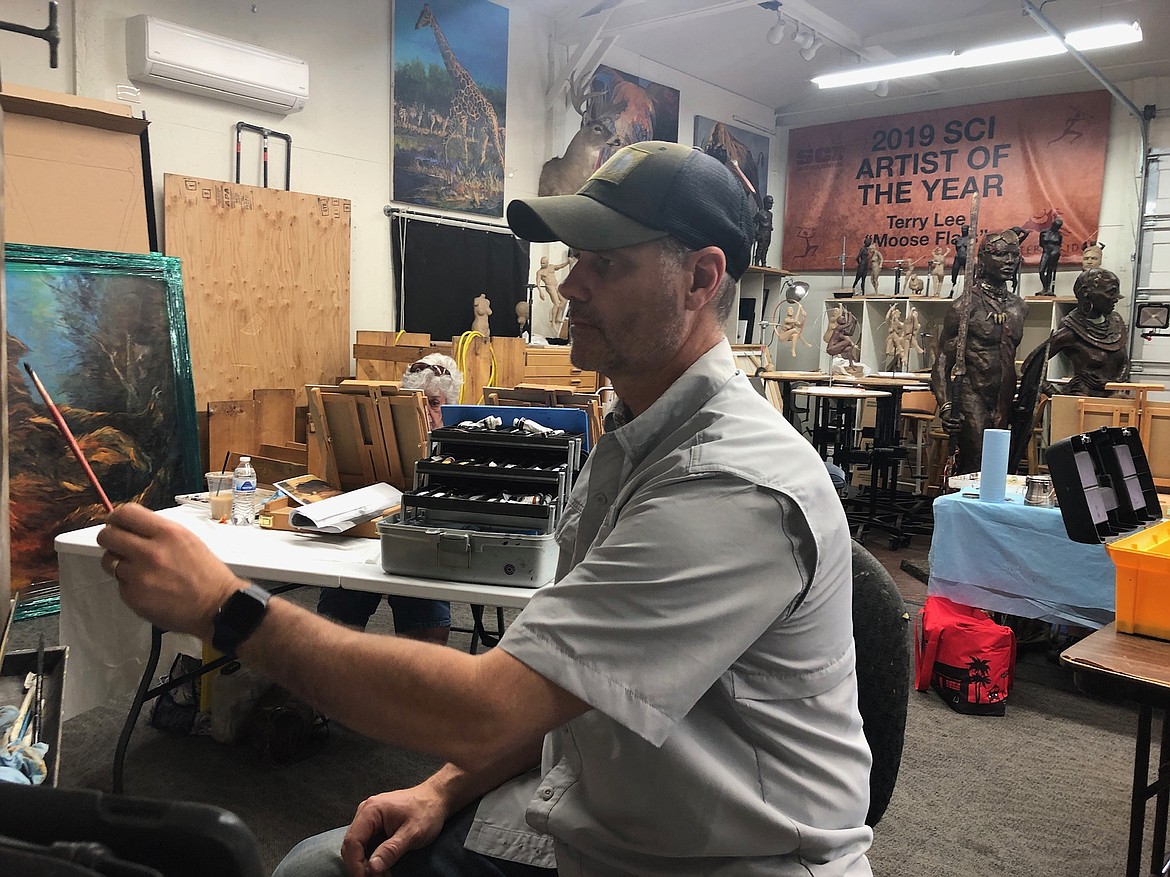

During a painting workshop led by Kronenberg at Terry Lee’s studio in July, artists brushed busily away, halfway through their paintings and the three-day workshop. Black and white buffalos on scratchy grass backgrounds peered from canvases around the room.

Kronenberg’s brush did the talking as he demonstrated a technique on a student’s canvas.

“All my life, ever since I was little, I drew,” he said.

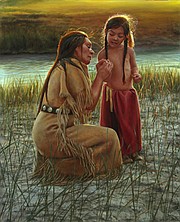

Kronenberg is best known for his realistic Western landscapes and portraits in oil.

Although the busy artist no longer has time to teach regularly, after many years teaching two days a week in Hayden and Spokane, he still holds workshops a few times a year.

Kronenberg’s own art education was somewhat atypical for modern artists.

“I went to art school and hated it,” he said. “I’m self-taught.”

After dropping out during his first year of art school, the Western landscape painter-to-be turned to the oldest method of learning in the book.

“I just looked at old masters and a bunch of artists, living and dead, and their techniques… taking bits and pieces of what I like.”

Before modern times, it was a common way to learn, whether alone or under tutelage. Like Kronenberg, artists would scrupulously learn to perfect different techniques.

“It’s a brilliant way to learn to paint. Not a lot of people do that as much anymore,” he said.

Now, most young artists are taught to focus on artistic expression, rather than achieving realistic subjects or specific effects in their work.

Perhaps as a result, modern painters increasingly favor less realistic or “looser” styles of representation (think Monet or Van Gogh).

“There’s a stigma about [how] everything has to be original from conception, right? And I think that the traditions of the old masters are lost a lot in that mindset, too.”

With his love of old masters, it’s perhaps no surprise Kronenberg is a realist. Although his paintings have a tendency to get “looser” further from the focal point, even his backgrounds tend to be less abstracted.

At the July class he shared a traditional technique called grisaille, where painters begin in shades of grey and neutrals, and then add colors in transparent layers on top.

This approach adds depth, Kronenberg says, and can help “difficult” colors like red to appear more saturated. In bright gallery lighting, the added depth means shadows gleam more.

“These translucent layers we’re going to put on create an insane amount of depth, especially when the gallery lights hit them.

The shadows will look almost black until you pop a gallery light on it. Then that transparent paint will show up beneath the dark.”

The technique was common to masters like Rembrandt, also known for rich contrasts in shadow and light. It’s also slow. The technique draws on layers of paint, but artists must wait hours or days for each layer to dry.

“So that means if I’m doing six glazes, I’m six days into this. I better have something else to work on as I’m building these glazes,” said Kronenberg.

He suspects the technique is no longer common, because many artists want faster results.

“[But] I think it’s a good thing for those artists who do want to take the time, because it gives you a unique look.”

Students at the workshop showed no lack of patience, or appreciation for the style.

“They’re supposed to get dry enough that we can start glazing [in color] tomorrow, but we’ll see if it’s dry enough,” said 90-year old artist Delores Hickey, testing a corner of her grayscale painting. “I doubt it.”

But the prospect of not being ready to add color on the final morning of the workshop was no bother.

“Oh its fun,” said Hickey. “It’s going to be fun to see what it’s going to look like when you get through.”

Fellow artist Michele Kennedy agreed.

“It’s fun to see how different everybody’s [work] is, too, because they really vary.”

Hickey and Kennedy are experienced artists themselves.

Hickey’s work has been shown in the region and she taught art to grades K through 12 in area schools. Kennedy also sells her paintings, and is about to open an Etsy shop for her handmade jewelry.

Both have been artists since childhood.

The two, like the other students, are regulars of Kronenberg’s workshops.

“Whenever he does one we love to come,” said Kennedy.

“He’s a fantastic teacher,” Hickey added. “A lot of teachers aren’t eager to share, but he shares everything.”

“He just wants you to do the best you can.”

Hickey and Kennedy also appreciate the realist style. Both noted the room for individual expression, despite adhering to a more natural look.

“If you go around, everybody’s background will be different, said Kennedy. “It’s fun to see them all kind of evolve.”

“You still have an expression in realism.”

“These guys are all painting the same thing but by the time you’re done everyone has a different interpretation of the same thing,” Kronenberg agrees.

“They don’t look like photographs,” said Hickey.

Pointing to a finished work of Kronenberg’s displaying the grisaille technique, she added, “It looks like a painting.”

“And that’s what I like to do, make it look like a painting,” she said.

“You hear a lot, ‘Well, I want to paint like you.’ [But really] they’ve got an idea in their head what they like, and they want to know how to get there,” Kronenberg added.

“I just try to direct them by sharing my process and then hopefully they’ll do the same thing I did and find bits and pieces of what they like.”

To see examples of his classic and stunning Western paintings and learn more about the painter see Kronenbergart.net or Joe Kronenberg Art on Facebook.