MOMENTS, MEMORIES and MADNESS with STEVE CAMERON: With their last pick in the 1978 NBA draft, the Denver Nuggets almost select ...

Speaking of draft choices …

And of course, that’s the sports story of the weekend around here, what with the Seahawks addressing needs (or not) in the NFL’s first-ever virtual draft.

We can talk about the Hawks and what they accomplished on Monday.

Draft guru Mel Kiper Jr. gave Seattle a bad grade overall, which probably means they hit the football lottery with their seven picks.

Today, however, we need to talk about the day I almost got drafted.

This was the National Basketball Association draft of 1978 and, OK, I more or less lobbied to be selected by the Denver Nuggets.

It didn’t work, at least not immediately.

I’d played hoops in high school, a little in college — and seriously believed I was going to be lights-out point guard at ANY level, if only my childhood doctor had been correct.

When I was 11, he’d looked at my hands and feet — large for my age — and predicted that I would grow to be 6-4 or 6-5.

Never happened.

THE GROWTH stopped just a whisker over 6-0, and I was left as a skinny lefthander who could shoot and pass — but struggled to guard anyone 6-1 and above, or bulky enough to shove me around.

So the dream of being an NBA point guard turned into a career in journalism.

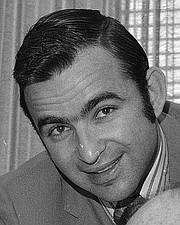

In 1978, as it happened, I was a sports columnist for the Denver Post, and covering the draft.

Unlike their secretive brethren in football, Nuggets executives let me sit in the “war room” as they made their selections.

To understand how I might been arguing that I should be drafted, you need to know that the NBA was nothing like the critical two-round affair that it has become these days.

In fact, there were 10 rounds (teams could pass in later rounds if they didn’t fancy anyone left on the board), and 202 players were selected that year.

The Nuggets had lost interest in the talent available as the final two or three rounds limped along, and I got the attention of CEO Carl Scheer and Coach Larry Brown.

I’D BEATEN assistant coach and former pro George Irvine (also a U-Dub grad) in consecutive games of HORSE, I argued, so why not have some laughs and draft a newspaper columnist in the last round.

With the urging of VP Bob King — who was always looking for publicity, even the oddest kind — Scheer began to think about it.

The Nuggets had chosen South Carolina guard Jacky Gilloon (more on him shortly) in the seventh round, and weren’t too high on any players after that.

“Why don’t we have some fun?” King asked Scheer. “What can it hurt?”

At this point, you should be aware that Scheer and I were pretty good friends, and part of a gang that ran 7 miles together every weekday — and ultimately took our talents to the San Diego Marathon.

“Go for it, Carl,” I said, as Brown (who is abnormally serious about basketball) frowned and shook his head.

Eventually, they decided relations with the Denver Post might seem too tight, since there was another competing daily newspaper in town.

But as you’ll discover, the idea of getting me into a Nuggets uniform stuck with Scheer.

SCHEER was never afraid to try something unusual. In fact, he was the inventor of the now-famous Slam Dunk Contest while working in the American Basketball Association.

In fact, when the Nuggets began play in the NBA after a 1976 merger, the entire Denver brain trust knew they’d have a sensational team in any league — what with David Thompson, Dan Issel and Bobby Jones on the roster.

So when the Nuggets made their first road trip to New York and Boston, trainer Chopper Travaglini hauled out the old red, white and blue ABA basketball for pre-game warmups.

It was an obvious shot across the NBA’s bow by the new kids from out in the mountains.

Scheer promptly received a cease-and-desist order on the ABA ball from Commissioner Larry O’Brien, who didn’t appreciate the upstarts from Denver humiliating any of the NBA’s old guard.

BACK TO the 1978 draft …

The Nuggets were coming to the 10th round of the endless draft, and by this time, Scheer and King DID have in mind to enjoy themselves.

They kicked around the idea of selecting actor Elliott Gould, who had been a basketball player at some point in his life.

King loved that idea (naturally), and suggested the Nuggets create a new slogan: “Go for the Gould.”

Once again, however, the commissioner was not amused by the Nuggets’ antics, and he refused to let them draft Gould.

I told Scheer afterward that he could have gotten away with drafting me, since no one in the NBA office would ever have heard of me.

Carl didn’t pull the trigger on that, but Brown had been paying attention all along.

When it came time for the Nuggets to begin training camp in the late summer of 1978, Larry pulled me aside and said: “So you really think you can play?”

I was WAY too cocky, and said: “Hell, yes!”

Brown threw down the gauntlet and promptly invited me to participate in the Nuggets camp.

NOTHING, absolutely nothing, can prepare a fairly athletic, decent-shape city league basketball player for the NBA’s alternate universe.

Yes, I trained with the Nuggets — mostly their rookies and second-year players — at their Boulder camp.

Brown made me take it seriously, which I was trying desperately to do, in any case.

I made a mistake on a screen during one drill, and Brown whistled play to stop.

“Steve,” he hollered, “you’re setting the sport back a hundred years!”

But God, I worked at it in that camp.

At one point, I stepped in and took a charge from Larry Taylor, a rookie from Arizona who was 6-9 and 240 pounds.

Brown said nothing about my bravery, but complimented Brown (despite his foul) for “always taking it up and over a smaller player.”

The highlight of camp for the players, I think, came when I tried to be a wee bit too clever.

After several days, I knew the plays and sets that Brown wanted to run.

So in this particular drill, I was on defense and responsible for checking Hollis Copeland, a 6-5 rookie leaper from Rutgers who went on to play some years in the league.

The other guard on offense was Robert Smith, already an NBA vet from UNLV (and my roommate in the dorm).

I realized that what the coaches wanted to run would start with a guard-to-guard pass from Smith to Copeland.

Just a split-second before Robert released the ball, I jumped out to steal the pass.

Except Robert saw me at the very last second, and held the ball. Copeland broke behind me for an emphatic alley-oop slam.

As the ball lay bounding around after the dunk, I had to go pick it up and Irvine — stationed under the basket — was grinning.

George said: “Pal, in the NBA, we call that…FACE!!”

Man, he loved that.

I DID have my moments, however.

The Nuggets rookies scrimmaged against Colorado, and twice I stole the ball from the Buffs point guard for coast-to-coast layups.

“I think you cost that kid his scholarship,” Irvine said.

But the whole experience was rough.

A normal person (like me) has to sprint all-out just to do full-court passing drills on which the pros are just loping.

It’s almost nearly impossible to get off a good shot.

I used a double-screen to find space in the corner on one play, put up a quick jumper, and second-year pro Bo Ellis from Marquette somehow leaped out from the lane to barely tip the thing.

Now, however, we come to my “scrapbook moment.”

Camp ended with the Blue-White charity game at McNichols Arena, which was then the Nuggets’ home.

More than 7,000 people turned out, and I was a bit terrified while Chopper taped my ankles — just like I was one of the guys.

“Hell, go have fun,” he said.

Right.

The assistant coaches each ran a team, and the boss on my side was Donnie Walsh, who ultimately became a great friend and president of the Indiana Pacers.

A few minutes into the game, Donnie said, “Are you ready for this? You look a little pale.”

INDEED, I’d no sooner checked in than I committed a turnover on a simple out-of-bounds play.

Ah, but there was vindication.

I played decent, physical defense (getting warned once by a ref for too much contact), bagged a couple of assists and even got two rebounds in 11 minutes of playing time.

And I scored.

On a 3-on-2 break, I was a trailer on the right wing and got a perfect feed from Gilloon (whom I love to this day). I took the pass in stride and hit about a 12-foot bank shot.

Scheer and Brown — and the crowd — all went nuts, but I wasn’t paying attention because I was fighting through bodies to get back on defense.

It only struck me later that I’d hit the shot.

I wound up missing a jumper later on (just a hair short, hit the front rim) and most annoying, I made only one of two free throws as we stalled out a win at the end.

Three points, my career NBA total.

It was fun to see my name in every box score category the next day.

I was in a lot better shape than when camp started (I’d have died if I weren’t), and brother, I got a taste of how good even rookies and younger players are at that level.

They’re from another planet.

The stars?

Impossible.

But hey, I still think I was worth a 10th-round draft pick.

Even ahead of Elliott Gould.

Email: scameron@cdapress.com

Steve Cameron’s “Cheap Seats” columns appear in The Press on Wednesdays and Fridays. “Moments, Memories and Madness,” his reminiscences from several decades as a sports journalist, runs each Sunday.

Steve also writes Zags Tracker, a commentary on Gonzaga basketball, once per month during the offseason.