Lessons in adversity from local experts: from World War II to 2020

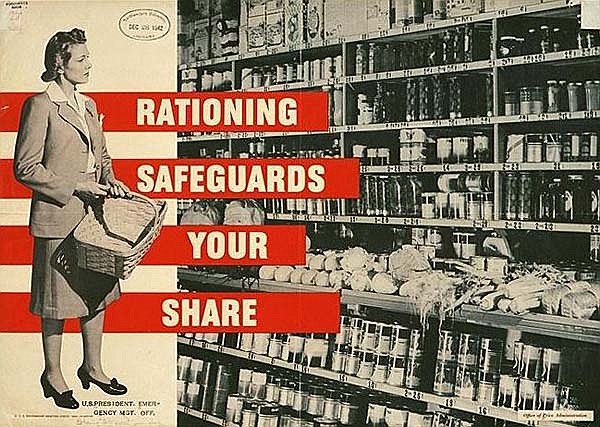

For some Americans, this marks the first time in their lives grocery store shelves aren’t brimming with any and every option, at least for some items.

But it’s not the first time in American history. World War II, with its rationing and scarcity, particularly stands out. With that in mind, Coeur Voice asked a couple of local experts for advice based on their experiences during that challenging time – in both the northwest U.S. and Europe.

Meet your experts:

Coeur d’Alene area resident Ruthie Johnson and late husband Wayne graduated – from high school and college respectively – and worked at a shipyard in Portland during World War II, doing their part for the world effort. Wayne also served for a time in the Navy before being discharged following an injury. Ruthie remembers rationing, making do and living life when a war was on.

At the time, Post Falls resident Gino Elroy was a boy in Monthey, Switzerland, a small but busy town of some four to five thousand people, which also supported a big chemical factory. In addition to navigating limited resources due to war time rationing, his family took in several war-time refugees and owned a restaurant.

Spokane, Washington and Portland, Oregon

In the fall of 1941, Ruthie Johnson was a senior at North Central High School in Spokane. She and husband-to-be Wayne were planning to get married after she graduated high school – and he finished college – that spring, but they delayed their marriage after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Wayne enlisted with the Navy and served until a plane crash left him severely injured, leading to his discharge.

“He was considered disabled, but he thought his mind was good and he could still walk. He thought the right thing to do was leave the disability [assistance] to those who needed it more.”

“He got out [of the hospital], we got married, and went to Portland,” Johnson said. There the couple worked in a shipyard – participating in their own way in the war effort.

“We found a small apartment, but we couldn’t get a car so we walked two miles to work and two miles home.”

Few were able to buy cars, which were being reserved for the military and other “important” workers. Gas was also rationed to be prioritized for military needs.

In addition to rationing, Americans were also encouraged to plant ‘victory gardens,’ Johnson said. The more people could raise their own food, the more might be left for the military.

“Everything was kind of geared toward the military,” said Johnson.

Johnson recalls trying to make groceries and paychecks last through the week, living on “skimpy” leftovers when they had to. Even so, they invested what they could in war bonds, as many were encouraged to do at the time.

“We tried to do what was honorable, to do what we could… to help people rather than be out there partying.”

Rationing increased their conservatism with food and resources. Johnson recalls red and blue food stamps - red for items like meat, butter, and oil; blue for canned goods, frozen vegetables, and soup. Clothing, shoes, coffee and sugar were also rationed.

“We did the best we could, but everyone had to go through it,” said Johnson.

“It was sort of like it is now.”

Even the ever-present uncertainty is relatable, she said. While the coronavirus disease is scary for many, Johnson adds that the threat of another bombing, like the unexpected Pearl Harbor, was an unnerving uncertainty of its own.

Monthey, Switzerland

Although he has lived in the U.S. for a long time, Elroy spent the War years as a child in Monthey, a Swiss city in the southwestern canton of Valais. Although Switzerland was neutral, many foods and goods were rationed, bombing was feared, and many refugees – from the U.S., Poland, France and Italy – were taken in.

“Probably about 20 to 30 percent of the people in our city had a refugee from either France or Italy,” said Elroy. His family hosted several, including two kids from Italy who stayed with them for a long time.

Families cared for refugees despite already limited resources and rationing.

“Even with refugees, we did not get extra coupons,” Elroy said. “We just used what we had.”

Food coupons, like those used in the U.S., entitled families to specific amounts of food. Meat was measured in grams, with children receiving less than adults. Although Elroy said folks could get a double portion from a horse butcher. Other goods, such as cheese, were also rationed.

“There were some things that were hard to get,” Elroy said. “I don’t remember having real rice until the war was over.”

Still, making do wasn’t always a pain.

The barley his family ate instead of rice gave no cause for complaints.

“Oh, it was good! We didn’t know the difference,” said Elroy. “The barley grain almost looks like rice.”

As in the States, sugar was also rationed. Instead, Elroy said, many carried little bags of saccharin (found in artificial sweeteners today). In Monthey, at least, honey was easy to come by and often made a reasonable substitution. Treats such as pies could rely on naturally sweet fruits.

Trading helped fill in the gaps amidst rationing.

“We did a lot of trading,” said Elroy.

“If you had chickens, you had eggs, which you could trade for something else.” Even stamps were traded.

In light of meat rationing, trading could be of particular use to big families in need of more protein. Elroy’s family used to trade with a local who hunted foxes, “[so] we had foxmeat!” he said. Traded or hunted, rabbits were also a good protein source – and for those who’ve never tried rabbit, Elroy says they taste good.

“We ate a lot of vegetables,” he said. “You had fruits and vegetables, plenty of fruits and vegetables.”

“We never got hungry,” Elroy said.

“Nothing was lost,” said Elroy. “Everything was recycled.”

People saved, reused, and repurposed more than food. Even cellars most houses had in case of a bombing also functioned as food storage.

“[We] put vegetables in it that came before the frost,” said Elroy.

Autumn vegetables such as onions, celery, carrots and potatoes could be kept easily in these dark, cool places below houses. Root vegetables in particular could be saved in sand or dirt and watered on occasion, so they were almost fresh when eaten. Giant jars of pickles were also often stored in these cellars. Even apples and pears might keep on cellar shelves, although these were checked periodically so any rotten fruit could be removed.

Old milk was used to make yogurt. Old clothes would find a new purpose. Old paper “waste” could be burned in fires and stoves.

And if the horses who pulled the garbage cart left something behind…

“…we used to go there with a bucket and pick it up,” said Elroy. The same went for cow manure found in the fields. Natural fertilizer.

Even newspaper wasn’t sacred. Toilet paper was not much better than crepe paper at the time, according to Elroy. A popular alternative was made from cut-up news sheets.

“Nothing was thrown out,” Elroy repeated.

Coeur d’Alene, today

For those who find the current climate unnerving, Johnson agrees.

“It’s kind of weird,” she said. Like many in care facilities, residents in Johnson’s home can’t receive visitors, are asked not to socialize with other residents, and eat separately in their own rooms.

Still, she keeps things in perspective.

“I don’t mind,” said Johnson. “There’s a lot of people who have gone through a lot, so we shouldn’t complain.

Elroy hopes people will learn to waste less and think of others more during these times.

“We live in a community. We should help each other.”

“And helping each other is not to hog everything,” Elroy added. “People should not be pigs and go to the store and buy everything.”

Johnson is also hopeful people will focus on one another’s needs and continue to help each other.

“I just think we live in the greatest country in the world and we have the most freedom in the world,” said Johnson.

“And if we have to go through these trying times, it’s just one of those things that you have to expect once in a while.”

And if all else fails, there might be another use for this newspaper.