Bullet holes and trash

By RALPH BARTHOLDT

Staff Writer

The television is propped precariously on a dirt mound in the Coeur d’Alene National Forest for easy viewing.

It can be seen from a variety of aspects through the sights of a pistol or rifle. From the edge of the road, a shot from a gun can reach it easily.

It is Swiss-cheesed with holes from bullets and pellets, but the thin screen stands, still, as if to dare a 30-caliber round to knock it off the mound.

Nearby, Bob Balser, 86, a National Rifle Association ball cap balancing elegantly over his tight scalp, picks up a canister that has been shot so many times its original use is barely distinguishable.

“I think at one time this was one of those little propane tanks,” Balser said, turning the hunk of steel in his hands.

Balser, a retired logger who grew up in timber towns from Emida to Hayden, has a proclivity for the forest that for more than a half-century provided the means to forge a living for his family.

This is his way of giving back — he cleans up swaths of land along rural Hayden Creek Road, a lumpy path, the gateway to the National Forest that others have turned into a wooded garbage dump.

Washers and dryers, carpets, rugs, tires, car parts, plywood, cast-iron sinks, pots and pans and a wash of bullet and shell casings all litter the forest floor and a gravel pit used by the public as a target range.

“If you can’t find it up here, it don’t exist,” Balser said.

Dressed in slacks, Romeo slippers and a jacket over a button-up shirt, the former logger moves between pitted pieces of rusted metal and plastic jugs ripped apart by gunfire.

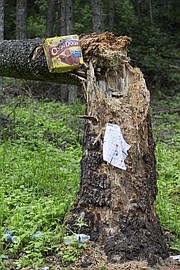

“I don’t know if that tree has enough bark shot off of it to kill it,” he said, stepping over deflated balls, beer cans, and part of an air conditioning unit thoroughly shot through as he walked to a still-growing cedar.

“Every one of these was a live tree,” he said nodding at stumps that look to have had their trunks chewed off.

He and his companion, Bo, a heeler, have driven for years in an older model Ford pickup — silver as Balser’s shaved-close pate — along Forest Road 437 a couple times a week as he cleans up what other people have dumped, shot and discarded.

“This has been an ongoing project of mine for several years,” Balser said.

He has organized volunteer groups to help clean up the area, including Boy Scouts, his friends and others concerned about the vandalism, illegal dumping and misuse of the stretch of public land.

Balser has adopted the forested road as others adopt highway ditches.

There is no road sign giving him kudos.

“This isn’t about me,” he said. His project is about drawing attention to the misuse — not only by shooters, but also by the off-roaders who tear up the land, leaving mud holes in the road and flat ground like heavily creamed coffee that drains into the nearby stream, he said.

But like the litter he regularly keeps in check, his helpers have fallen by the wayside. The work is without gratification because the abuse of the small chunk of land north of Coeur d’Alene does not stop, he said. A fellow volunteer quit recently.

“He said, 'This spring, I’ve done enough of this, I’m done,'" he said. “I don’t blame him. I’ve thought the same myself.”

The Forest Service isn’t much help out here, and Dan Scaife, the district ranger, knows it. His organization is run by tax dollars that are stretched thin, and there is no budget for road maintenance or cleaning up the mess.

He teams up with Balser on cleanup days and often goes out by himself to pick up junk, litter and debris, but he cannot do much for the condition of the roads.

“We don’t have a road maintenance budget,” Scaife said.

Pounding through mud puddles, widening them, churning them and deepening them until they become almost impassable with conventional vehicles is discouraged, he said, but it’s a motorist’s responsibility to take care of the public thoroughfare.

“Money is pretty tight,” Scaife said. “That’s all the more reason not to tear up those areas.”

Fely Schaible, a law enforcement assistant in the 750,000-acre forest, said citations are written but because of the dearth of uniformed officers in the chunk of forest that encompasses the entire Idaho Panhandle, vandals tend to go unpenalized.

Schaible forthrightly cites the fines.

Destroying trees or vegetation: $205 including court costs. Mud bogging: $250. Polluting streams: $250. Dumping: $500. Littering: $130.

The agency puts up information signs to let people know about violations, she said.

“They are torn down as quickly as we put them up,” she said.

The lack of respect for public land is disheartening, not only for Balser’s friend, who quit cleaning up after others, but for officers like Schaible, and for Balser, too, who has heard rumblings by Forest Service officials of potential closures if the vandalism continues.

“To me, the sound of gunfire out there on those ranges is the sound of freedom,” Balser said. “If I don’t do this, they are going to close. And I don’t want to see that. People will lose that freedom.”

The litter on the homemade ranges paints shooters in a poor light, he said. And it casts a pall over hunters too. Not to mention, he said, the land belongs to everybody and should be used responsibly.

“These jerks are giving us all a bad name,” he said. “But what do I know, I’m just a dumb lumberjack.”