Behind bars

High above the concrete walls topped with loops of barbed wire on all sides, the sky was a cloudless blue.

Inmates at the Kootenai County jail used to play basketball in recreation yards like this one — but that was 15 or 20 years ago, said Captain John Holecek, who’s been with the Kootenai County Sheriff’s Office for almost 29 years.

“That was one of our in-custody deaths,” he recalled, referring to an inmate who suffered a heart attack while playing basketball.

There were 312 inmates at the Kootenai County jail on Wednesday, when County Commissioner Bill Brooks went on a quarterly tour of the facility.

“I come here every three months, and every time, they’re making improvements,” Brooks said.

About 85 percent of those currently incarcerated are facing felony charges — a reversal from years past, said Sheriff Ben Wolfinger, when misdemeanor offenders made up the bulk of the inmate population.

Even so, incarceration numbers are down compared to last year, Wolfinger said. Fewer arrests are being made. This is partly because of increased efforts to cite and release misdemeanor offenders in order to minimize the number of people in jail during a pandemic.

Wolfinger pointed to another factor — a 2019 Idaho Supreme Court case which ruled that officers cannot arrest suspects for misdemeanor offenses without warrants if they have not observed the alleged crime. The ruling has limited officers’ ability to respond to domestic violence calls, Wolfinger said.

As of Wednesday, 55 of the inmates in the Kootenai County jail were sentenced and bound for a state facility. Under normal circumstances, these inmates are picked up every 14 days, but COVID-19 has slowed the process. When inmates aren’t transferred in a timely manner, this puts a strain on resources.

“We’re not set up to be a prison,” Wolfinger said. “We’re set up to be a jail.”

The pandemic necessitated many other changes. Inmates are issued masks. Gatherings like Bible study and domestic violence counseling were halted for months, and those spaces were instead utilized for remote hearings while courtrooms were closed. All visits occur via kiosks, rather than in-person.

COVID-19 hit inmate workers first, Holecek said — inmates who do laundry, kitchen and janitorial duties.

All told, 67 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the jail, among inmates and staff. There were no current cases as of Wednesday.

New inmates are checked for symptoms and then isolated for five days, in case they were exposed to the virus before arriving at the jail and develop symptoms. Inmates are then tested for COVID-19 before entering the general population.

A tired-looking face peered from a holding cell near the booking area. The yellow sheet posted beside the door indicated that the inmate must be checked on every 15 minutes.

“Suicide watch,” Holecek explained.

Two inmates have attempted suicide in recent months, he said, despite precautions in place for their safety, including special clothes that can’t be used to harm themselves.

Inmates who struggle with mental health issues face certain challenges in jail, Holecek said. It’s crucial that inmates receive appropriate treatment, but the resources aren’t always available.

“We work as hard as we can to get them into a hospital for treatment, but there are only so many beds,” Holecek said. “It takes time.”

Medical care is the jail’s single greatest non-staff expense, he noted. About $2 million goes toward medical care for inmates each year, including $1.7 million for a private contractor.

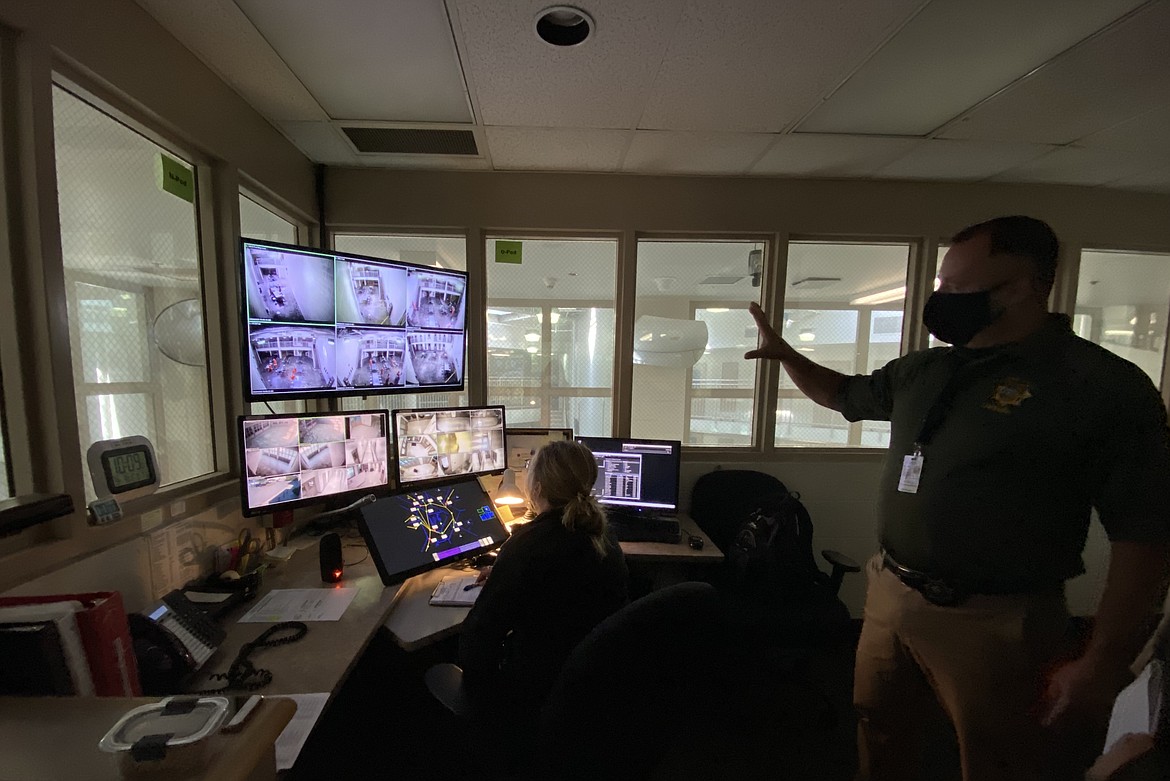

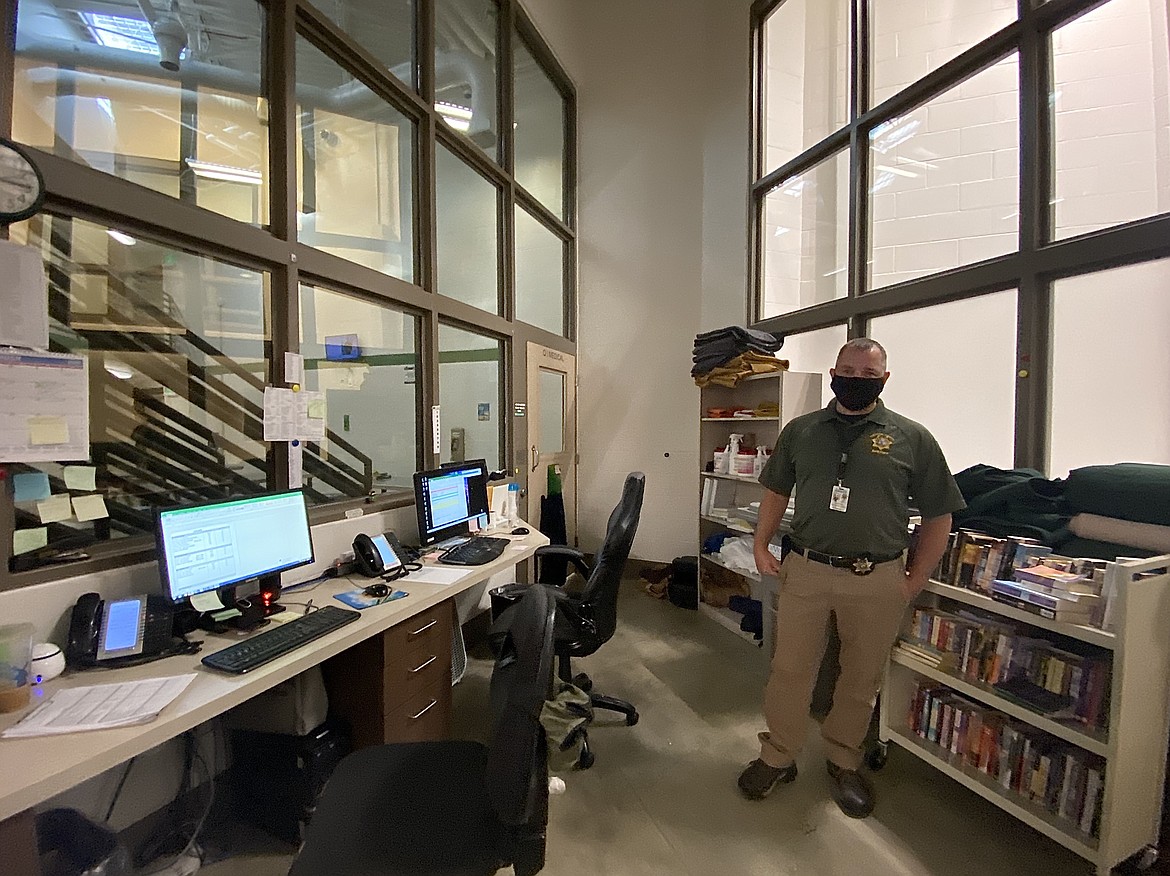

In one corridor, carts were stacked with books for inmates to read — fantasy novels, romance, self-help. A lone man made a phone call in a dormitory pod; above, behind reflective glass, a deputy observed him and other inmates from a dimly-lit control room that had an array of screens. Throughout the jail, 180 cameras record activity.

The Kootenai County jail can accommodate up to 452 inmates. After that, it would become necessary to send inmates out of the county to be housed elsewhere.

Steady population growth means that the need to further expand the jail is inevitable.

The shells of two new dormitory pods are built but incomplete. Jail staff currently use the space as makeshift break rooms. In one corner, a standee appeared to have been recently used for Taser practice.

Each new pod would house up to 58 inmates, significantly increasing the jail’s capacity.

That’s the next challenge Holecek anticipates — after COVID-19.

“Once we hit capacity, it’ll be bridging the gap between that and the process of finishing the new wings,” he said

He added that the project would take about a year and a half to complete.

“Commissioners need to be very responsive to this,” Brooks said.

That, he added, is precisely what he intends to do during his term as a county commissioner.

“You’ve got a friend in me,” he said.

On the latter half of the tour, Holecek pointed out another rec yard — a bigger one that can accommodate around 50 inmates at a time.

The sky above was still clear and blue, though this time, it was visible through metal bars.