Life of a Danish sea cook and the 'blond Eskimos'

Christian Klengenberg Jorgensen died in 1931 in Vancouver, British Columbia, where he retired after a lifetime in the frozen Arctic. They took his ashes back to remote Victoria Island north of Canada and scattered them at Rymer Point, where he’d built a trading post.

They called him “Charlie,” describing him as a sea cook, whaler, trapper, trader, and world-traveler. But he’s best remembered for seeing “blond Eskimos,” and for the dark side of his life.

He was accused of murder, tried and acquitted — though many believed he was guilty. Then just a few years later, a Royal Canadian Police constable mysteriously drowned and Charlie was again suspected of murder.

He was born in Denmark in 1869, his father a soldier, cabinet maker and wood carver. He was one of 16 children — eight being half-siblings from his father’s second marriage.

Young Charlie grew up Lutheran but seemed more interested in mythical Norse gods Woden and Thor that he learned about from his mother — who was of Viking descent.

At age 16, Charlie went to sea as an assistant cook aboard a ship named Iceland, sailing from Sweden to New York. His years at sea included Scotland, Russia, Australia, Hawaii and California.

In 1893, he jumped ship in Alaska, and at Point Hope on the northwest coast met his future wife, Inuit Eskimo Gremnia — also called Grenameh, Qimniq or Kenmek. The following year, they married and had nine children.

He would spend the next 11 years trading and whaling among the Inuit.

Then in 1905, Captain James McKenna hired him as skipper of the trading ship Olga to hunt whales in the Arctic with another ship, the Charles Hanson.

On a whaling trip years earlier, Klengenberg had spotted Inuit footprints on Banks Island next to Victoria Island and secretly planned someday to find the Inuits and trade with them.

He convinced McKenna to let him look for them on the upcoming whaling trip, but was ordered to stay within sight of the Charles Hanson. However, bad weather separated the two ships, with McKenna returning to the whaling outpost on Herschel Island, while the Olga — with the Klengenbergs, three other families and nine crew members — holed up for the long freezing winter at Penny Bay on Victoria Island.

While on the island, their camp became a trading post and base for trading with the Inuits in the region. Klengenberg told McKenna he couldn’t return sooner because of ice conditions.

Herschel Island in those days was a lawless outpost of whalers hunting in the Beaufort Sea for the endangered bowhead whale, prized for its baleen, blubber and oil.

McKenna was pleasantly surprised to see the Olga show up the following summer — believing the ship had been lost — but the euphoria only lasted until he learned that four of the crew members didn’t make it.

Klengenberg said that one crewman died of scurvy; two others disappeared on a hunting trip, and that he shot the fourth because he was using the flower and sugar to make homebrew and became violent when confronted.

Then the whole Klengenberg family hastily returned to Alaska by whaleboat.

After they left, surviving crewmen told a different story about what happened aboard the Olga.

They said that Klengenberg shot Jackson Paul, the ship’s engineer, twice. The second time was while Paul was lying in bed recovering from the first shot. They claimed two hunters who mysteriously disappeared were witnesses to the Paul killing, and a third witness died of starvation while chained to a bed in the ship’s hold. (Details differ among various accounts.)

When an American commissioner heard those charges, he reported it to authorities in San Francisco. Though the alleged crimes occurred in Canadian waters, Canada gladly turned the matter over to the U.S. to handle.

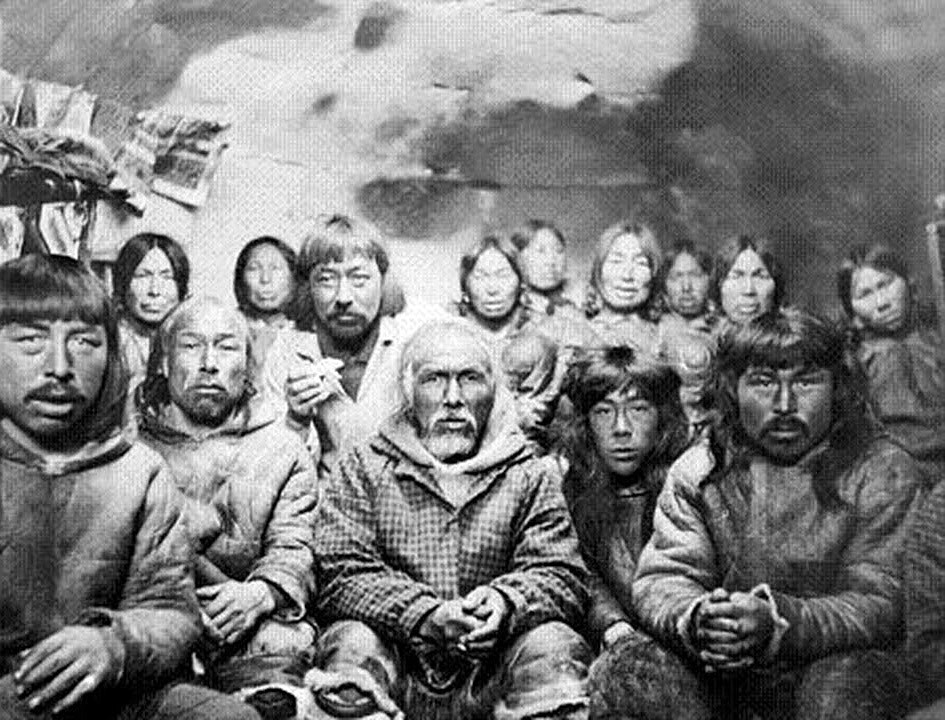

Before leaving for Alaska, Klengenberg met Canadian anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson on an exploration expedition, and told him that on Herschel Island he had met “blond Eskimos” who’d never seen a ship or a white man before. He described them as having European features and coloring.

Klengenberg would be forever remembered for coining that phrase. Stefansson however preferred calling them Copper Inuits because they used copper tools and weapons, while the newspapers later liked “blond Eskimos” better.

Stefansson, who switched to an Icelandic name from his birth name William Stephenson, was leading the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913-16, on a scientific exploration of the Arctic.

A 1912 article in Nature by David MacRitchie says that Stefansson had discovered 13 tribes of white Eskimos living near Coronation Gulf — which separates Victoria Island from the Canadian mainland — claiming that they were descendants of Norwegian colonists in Greenland.

“Ethnologically,” MacRitchie wrote, “the white Eskimos bear not a single trace of the Mongolian type, differing in the shape of the skull and general features, colour of eyes, and texture of hair, which in many cases is red. They spoke Eskimo, though the explorer thought he detected some Norse words. They probably numbered two thousand. Many of them had perfectly blue eyes and blonde eyebrows.”

American explorer and army general Adolphus W. Greely wrote that Dutch traders had seen them as early as 1656.

A detailed map shows sightings of “blond Eskimos” from the Yukon north shore across from Victoria Island to the east coast of Greenland and as far south as Southampton in northern Hudson’s Bay. Multiple research studies report contact between Europeans and Arctic native peoples from about 1000 A.D.

It’s now more than a century after Stefansson visited the Inuits and concluded that the “blond Eskimos” were either descended from Norse colonists in Greenland, or descendants of white whalers, or were “European-like” people who came across the Bering Strait.

He didn’t think it was the whalers because they had already been in contact with Inuits in Alaska for 100 years and there were no blond Eskimos there.

Stefansson and Klengenberg ended up not liking each other very much. Stefansson praised Charlie with one hand and whacked him with another — “He had a reputation for enterprise, energy and fearlessness, but he was also known to be unscrupulous, ruthless and two-faced… I came to accept Klinkenberg (sic) as a kind of legend in which I only half-believed.”

In return, Klengenberg likened the anthropologist to the brutal sea captain character Wolf Larsen in Jack London’s novel “Sea Wolf.”

Back in Alaska, Klengenberg returned to living and trading among the Inuit. During that time, U.S. authorities followed up on the Olga case, indicting him in absentia for murdering Jackson Paul. When he heard about it, he turned himself in and was tried. In 1907, he was acquitted because witnesses couldn’t get their stories straight.

In 1924, Charlie Klengenberg was sailing his ship, the Maid of New Orleans, from Alaska to his trading post on Victoria Island, stopping at Herschel Island. There, he was surprised to learn that American ships were not allowed to bring foreign goods into Canada.

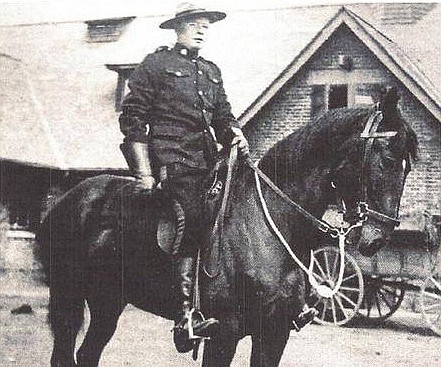

Klengenberg asked for special exemption and be allowed to import just one year’s supply of goods for use by his immediate family. Permission was granted, but only in exchange for picking up Royal Mounted Police constable Ian M. MacDonald at Baillie Island first. He was the 22-year-old grandson of Sir John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first Prime Minster and founder of the RCMP.

The constable was picked up and his official assignment was to make sure no unauthorized goods were being offloaded from the American ship — undoubtedly rankling Captain Klengenberg.

On the trip, MacDonald mysteriously disappeared, and they only found his parka and notebook floating in the icy waters. With a reputation for violence dogging him since the Olga trial, Klengenberg was a suspect. But when no supporting evidence was found, the incident was declared an accident and closed.

Since the 1920s, scientists have been studying Stefansson’s reasoning for how there could be blonds among the Eskimos. They still don’t have the answer.

In 2003, geneticists and anthropologist Agnar Helgason and Gísli Pálsson from Iceland compared DNA from 100 Victoria Island Inuits with DNA from Icelanders. No match. Since then, Pálsson from the University of Iceland has rejected Stefansson’s conclusions.

It’s a good thing that there are mysteries like this — they keep historians and history buffs fired up in mankind’s never-ending search for knowledge and truth.

- • •

Contact Syd Albright at silverflix@roadrunner.com.

- • •

Charlie Klengenberg the man…

“He was a tough man raising a large biracial family at the edge of the known world in one of the harshest environments known to mankind. He ignored the law when it suited him, and followed it when he had no choice. He was an explorer, trader and the founder of an Arctic dynasty. He also had a sense of humour: Among the many ships and barges that he owned at various times was a scow named the Homely Hippopotamus.”

— Kenn Harper, historian, Nunatisaq News

Dream fulfilled…

“I had found a land and a people where I could be the first to trade, and I made up my mind that eventually I would have my own ship and my own goods and go back with my family to Victoria Island and found a permanent trading post.”

— Christian Klengenberg

Young Klengenberg’s gods…

Among Norse gods, Woden represents wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, battle, sorcery, poetry, frenzy and the runic alphabet. He’s the husband of the goddess Frigg (or Freya), that the weekday Friday is named after.

Thor is the god of thunder, lightning, storms, oak trees, strength, protection, fertility and making things holy. He’s usually depicted carrying a hammer.

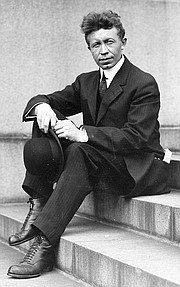

Death of Patsy Klengenberg…

Christian “Charlie” Klengenberg’s eldest son Patsy owned a schooner named Aklivik. In 1946, he lost his life in a massive engine room explosion. When he was about ten he was hired by the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1915 as a guide and interpreter — speaking the Inuit language. The scientist taught the lad reading, writing, math, geology, natural history and modern techniques for treating and preserving furs.

HELP WANTED

With all the scholarship available on Christian Klengenberg, it’s surprising that in searching through several thousand images on the internet, there were none depicting the “blond Eskimos.” If any reader can find an authentic one (beware of Photoshop), please email it to Syd with source information and we’ll print it (with credit) next Sunday (silverflix@roadrunner.com).

- • •

‘Look for History Popcorn every Wednesday brought to you by Ziggy’s.’