The people's right to know

By BRIAN WALKER

Staff Writer

COEUR d'ALENE — Government officials, attorneys and journalists went at it for three hours together Wednesday afternoon in Coeur d’Alene.

But in this round of the traditional tug-of-war over public records and open meetings, the players kept their eyes on the prize: The people's right to know.

They even stepped into each other's shoes in skits to gain a better understanding of those laws.

About 115 people from throughout North Idaho witnessed and heard how keeping public records in the public eye benefits everyone during an entertaining workshop at The Coeur d'Alene Resort held by the Idaho Office of the Attorney General and the nonprofit Idahoans for Openness in Government.

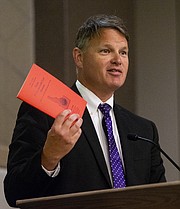

"Agendas, minutes, budgets, audits should be routinely released and that goes for cities, counties, school and highway districts and mosquito abatement districts," said Attorney General Lawrence Wasden. "If you're spending money, the public has the right to see what's going on. It is important that we recognize that the public has a right to see these and that we respond accordingly."

Forty-five of these sessions have been held statewide since 2004, and this was the fourth time one was held in Coeur d'Alene.

"We believe they're making a difference, and that's why we're doing them," said Wasden, adding that there are constantly new journalists interested in reviewing public records and new public employees and officials tasked with maintaining them. "Instead of us trying to train government employees and talk to the press, we believe it's best to put everyone in the same room so everyone is on the same page of music even if we don't always sing the same tune."

The workshops typically draw between 40 to 100 attendees, so Wednesday's turnout was among the best-attended.

"The strong turnout reinforces the idea that the people's right to know is just as important to many public officials here as it is to journalists," said Mike Patrick, managing editor for The Press, a co-sponsor of the workshop with The Resort.

"From the Kellogg school superintendent and the Sandpoint city attorney to members of local urban renewal agency boards and highway districts, we're all after the same thing: Understanding the law so citizens will have the information they need to make good decisions."

When journalists and public officials often cross paths, trust can be built, but other times conflicts arise and attorneys are sometimes called upon to settle public records disputes. The Press and the Coeur d'Alene School District, for example, disagreed last year whether the outgoing contract the district's former superintendent received should be revealed. After two refusals, the district agreed it was information that should be shared with the public.

"What I really appreciate about these workshops is the spirit of cooperation they bring out in people who don't always see eye to eye," Patrick said. "Instead of being upset about that, the school board's leader, Casey Morrisroe, was here today participating in one of the skits."

Wasden estimates the media and governments are both right about half of the time in public records disputes.

"If you're batting .500 in the majors, you're doing a great job, but if you're batting .500 in public records (disputes) that's not good so we want to increase that batting average," he said.

Brian Kane, Wasden's chief deputy, said he sees Idaho's open meeting law as the “ticket to the show” and the show is government at work.

"You have the ability and right to observe your government in action," he said. "It is not necessarily your right to participate. I often hear from citizens that boards did not let them speak, but, unless there's an open forum you don't have the right to speak."

Notices of regular meetings must be posted at least five calendar days in advance and agendas 48 hours in advance. A new provision that takes effect July 1 calls for meeting notices and agendas to be posted electronically if the public agency has a website or maintains a presence on social media.

Another new provision requires that meeting agenda items that may be voted on during a board, council or commission meeting must be identified on the agendas as “action items.”

Executive sessions, which are not open to the general public, need to be authorized by at least a two-thirds vote and there must be specific reasons cited for holding them, including, but not limited to, when hiring a public employee, considering the evaluation, dismissal or disciplining of a public employee, acquiring property and to communicate with an attorney about pending litigation. Decisions can't be made in executive sessions.

"I'm a little suspicious about some of the stuff that goes on behind closed doors," said, Betsy Russell, a newspaper reporter, IDOG co-founder and workshop presenter.

Russell said, when it comes to understanding open meeting and public record laws, "We're all in this together."

Failure to comply with the open meeting law can result in a civil penalty of up to $250, up to $1,500 for "knowingly" not complying and up to $2,500 for subsequent violations within a year.

Kane said the hardest part of not complying with the law is to admit a mistake was made. If an admission is not made, a complaint may be filed in district court and the matter could then escalate into a story in the newspaper.

"We don't expect you to be perfect, but we expect you to comply," he said.

Kane shared a tale of two boards that had violated the open meeting law. In one case, a confession was made and another meeting was held to rectify the mistake. That matter drew a short blurb in the newspaper.

Another case, in which the governing board erred in following the law but would not admit it, resulted in a court complaint being filed against the board. The filing prompted a front-page story, and another story when the district judge declared the board had violated the law, and yet another story when it was appealed to the Idaho Supreme Court. Then, there was a story about how much taxpayer money was spent by the board fruitlessly defending its position.

"Sometimes the learning curve is steep," Kane said.

Kane equated the public record law as the public's fishing license.

"It's your license to find what you're looking for — and maybe not find what you're looking for," he said.

The state defines a public record as "any writing containing information relating to the conduct or administration of the public's business."

Public records requests must be granted or denied within three working days, according to Idaho law.

Kane encouraged public employees to keep in mind they are working in the customer service business, so responding before the three days, if possible, is common courtesy.

"If I get a request, my goal is to get that off my desk as fast as humanly possible," he said. "If I don't, there's a chance it could get buried."

If a public record is not released, the sole remedy is to go to court.

"I understand that's a hurdle, and maybe the Legislature will consider a non-judicial remedy," Kane said.

There are more than 100 exemptions under Idaho's public records law, including personnel records, trade secrets, emergency response plans and library records.

The Idaho Attorney General’s Office publishes manuals with the state’s open meeting and public records laws. They can be found online under “Office Publications” at www.ag.idaho.gov.