Being 'Good Neighbors' boosts forest health

Forests know no jurisdictional bounds. Insects, fire, and disease spread quickly without a thought to who has authority to stop them. So to be successful, efforts to manage forest health, and its impacts on people and critters, can’t focus on who owns what.

That’s where Good Neighbor Authority comes in: Not so much tearing down the fence between federal and state-owned forests, as creating a gateway to manage together, to the tune of 11 Idaho projects and counting. Idaho contains 20 million acres of U.S. Forest Service land; 63 percent is eligible for management (the rest is roadless and wilderness areas).

“Of that, our assessment showed 8.8 million is at risk to insect, disease and fire conditions,” said Craig Foss, Idaho Department of Land’s Forestry and Fire Division Administrator. “So 70 percent of that manageable land base is at high risk.”

GNA allows the state to accomplish what the feds can’t, or can’t right now — work crucial for historically declining forest health and to prevent more record-breaking and financially devastating forest fires. Results have been encouraging, with once-stalled efforts in federal forests moving forward, including thinning, restoration, and timber sales.

“The national forest system land… has been in a pretty steady decline since the 1970s, and mortality in the national forest is at an all-time high,” David Groeschl, deputy director and state forester for the Idaho Department of Lands, told NWM&T in an interview for its first GNA story in 2017, the year IDL started work in national forests.

All environmental laws still apply, but IDL fills in where the Forest Service is constrained by regulations, time (state and federal budget cycles begin in different months), or resources.

“For example, when they’re short of specialists, such as from a slow hiring process or a hiring freeze, through the GNA agreement we can advertise and award a contract to an individual to get it done,” explained Foss.

Jon Songster is IDL’s Federal Lands Program Manager and oversees the statewide GNA program, from planning to on-the-ground implementation

“In the Idaho Panhandle National Forest, the USFS has 40 vacancies to fill,” he said. “That can be a bottleneck. This is a way we can add capacity and help — with internal staff, or going to private sector and bringing those professional services in.”

One example is the Hana Flats project where the state provided a hydrologist, fisheries, and soil specialists who enabled a NEPA project (environmental impact analyses required for work on federal land) to move forward.

“We used GNA authority recently to help us in the priest lake area (Hana Flats),” said Matt Staudacher, Idaho Panhandle National Forest Service Vegetation Staff Officer, who is in charge of GNA restoration work. “All our NEPA employees were working on different projects, so we combined forces with the state to contract with environmental firms and put together a team… It would have taken another year, possibly two, by the time we got to it. So we were able to start it a year earlier.”

The legal framework for GNA cooperation began with the 2014 farm bill — a four-year law covering an array of federal agricultural and food programs considered again in 2018. The program’s first two years were about planning; IDL and USFS entered a joint Good Neighbor Agreement, and identified projects and priorities. GNA implementation in Idaho during the start-up phase benefited from financial contributions from forest products industry partners, who are contributing $1 million over three to five years in support of GNA work by Idaho Department of Lands. Projects involve mixed ownership settings and contribute to cross-boundary restoration outcomes. In many cases private forestland abuts public forest.

“We work collaboratively with partners such as tribes, county commissioners, and collaborative groups to create a five to 10-year action plan — so we have all our integrated vegetation projects planned out for 10 years,” said Shoshana Cooper, IPNF’s public affairs officer. “GNA gives us the flexibility to fill resource gaps allowing us to potentially bring some projects forward ahead of schedule to accomplish more restoration work across the forest.”

That private-public philosophy of joint stewardship has been a boon for forest management.

“The whole idea of shared stewardship is based on trust,” said Songster, who works directly with USFS program managers for each forest. “One reason it’s worked so well in Idaho, especially in the panhandle, is that trust — we work well together to get more done on the ground. The relationships have been very positive, with folks working shoulder to shoulder.”

The state fills in where needed to create efficiencies rather than duplication. GNA’s goal is to become self-sustaining by 2021, if not sooner.

“Our goal is for this to be additive — meaning it’s in addition to what that that forest might ordinarily achieve in a year, according to the FMP (forest management plan),” said Foss. “We don’t want to do work they’d already be doing with existing staff and resources, but to increase the pace and scale of restoration.”

In addition to the industry contributions, operational costs are funded by $300,000 annually from the USFS, as well as yearly state appropriations ($750,000 for FY2018). This year, IDL asked for budget authority to hire seven additional people and create an oversight bureau.

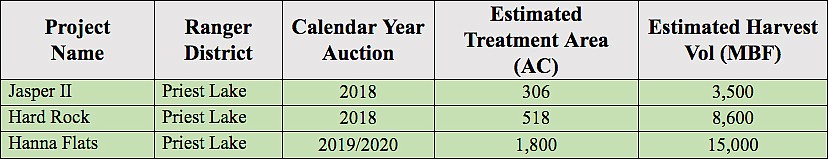

GNA money flows in both directions. Sales of federal timber — much of which wouldn’t have been possible without GNA authority — have thus far generated more than $2 million gross revenue. The first IPNF GNA timber sale was awarded to Stimson March 1, 2018 and will remove dead and dying timber from 306 acres north of Priest River. Another in the Nez Perce was a salvage sale from a 2015 wildfire. Forest officials on both sides say it’s paying off in forest health, and will soon pay off even more financially.

That income finances non-revenue work including stream cleanup, vegetation management, and road maintenance. Road reconstruction is a concern; some areas of national forest can’t be accessed areas for management — leaving disease, insects, and fire fuels unaddressed. Road reconstruction was left out of the 2014 farm bill’s GNA authority; the hope is that will be fixed in the 2018 bill.

“This is a well-known issue, and other states are also concerned,” said Songster. “It’s problematic because if the project includes a timber sale, the revenues could stay in the program and be applied on the national forest. But there is an incredible backlog of roadwork on every national forest in the state.”

Meanwhile Idaho GNA teams just work around it.

“What we’ve been able to do up to now is identify projects that don’t require road reconstruction,” explained Foss. “But it remains a significant barrier, because there are high priority areas where both agencies would like to do work. Usually when you set up a timber sale, you set up the road as a part of it, and the sale pays for that work.”

Cooperation under GNA extends beyond forest ops. IDL and USFS are also sharing knowledge, attending one another’s trainings and learning applicable regulations and methodologies, which could lead to improved efficiencies on both sides. Staudacher said he’s learned a lot about state processes.

“We’re combining forces to get the most for the forest. We are shooting for that sweet spot of cooperation, those synergies.”