Vancouver Island's Ripple Rock explosion and other big blasts

Like a malevolent monster awaiting its next victim, Ripple Rock lay hidden just 9 feet below the surface of the Seymour Narrows between Vancouver Island and the Canadian mainland, the waters above swirling in dangerous eddies that over the years claimed 114 lives and sank or damaged more than 120 ships.

Even British explorer and Royal Navy Capt. George Vancouver in 1792 described it as “one of the vilest stretches of water in the world.”

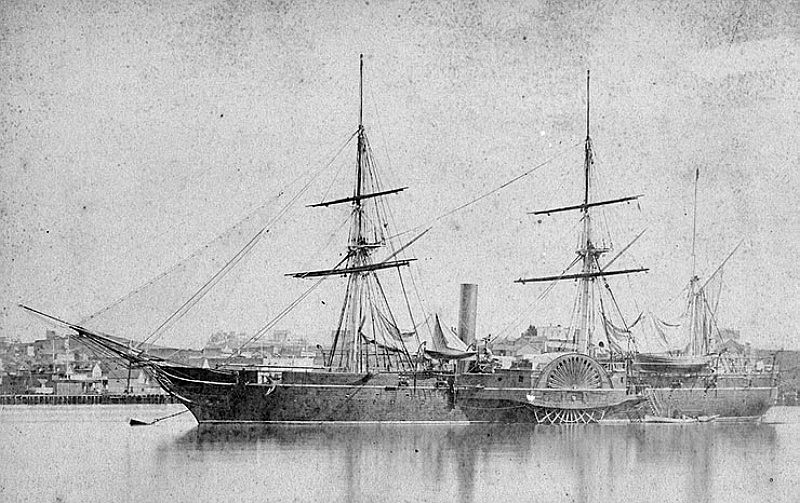

One of the Rock’s victims was the Civil War side-paddle-wheeler steam and sail sloop-of-war USS Saranac. Built in 1848, the ship served the Union during the Civil War, and in 1875 was assigned to collect “natural curiosities” for the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 — the first official World’s Fair in the United States.

Entering the Narrows, pilot William George warned Capt. Walter W. Queen to wait to flood tide before proceeding. The advice was not taken.

Crew member Charles Sadilek later wrote in his journal, “I have never seen an inland body of water more threatening than Seymour Narrows. Even the ocean in a temper has no such ravening aspect.”

At 8:45 a.m. on June 18, 1875, the Saranac hit the submerged Ripple Rock.

“When in a midst of a whirlpool,” Sadilek continued, “the ship refused to answer her helm and was for a moment beaten about by the angry water, when all of the sudden there came a crash that shook the ship as if it had been fired by a battery of guns… The fearful rush of water as it closed over her was so powerful that it would have killed any living being who might have been aboard.”

The crew managed to run the ship’s bow onto the shore on Vancouver Island and tethered it to a tree, but an hour later the stern filled with water and the Saranac sank in 300 feet of water.

Fortunately, no one died and the crew of 15 walked 165 miles to Victoria.

For about 75 years, the Rock and its swirling waters remained a maritime hazard. Then Vancouver residents talked about using it as a foundation for a bridge linking the island with adjacent Maude Island and the mainland. Others, however, wanted to blow it up.

Several efforts at demolition failed, but in 1958 an amazing underwater demolition plan was adopted that would take 17 years to conceive.

“In a procedure similar to a root canal,” as one report described it, 75 men spent 27 months digging a tunnel beneath the Narrows and up into the two peaks of Ripple Rock.

A vertical shaft 570 feet deep was dug on Maude Island, and then continued 2,400 feet west under Ripple Rock. From there, two 300-foot vertical shafts were excavated into the Rock’s twin peaks, and packed with 1,247 tons of explosives.

With a horde of news photographers and writers present and millions watching on television, they pressed the button at 9:31 a.m. on April 5, 1958, setting off an explosion then called the world’s largest man-made non-nuclear explosion — though the Russians and Chinese claim larger ones.

The blast obliterated 336,000 tons of rock and displaced 290,000 tons of water, reducing the height of Ripple Rock by 38 feet.

No longer a navigational hazard, a million passengers aboard luxurious cruise ships pass through the Narrows every year, along with other maritime traffic.

Nuclear blasts were far larger, of course — The United States’ biggest one being hydrogen-bomb “Castle Bravo” at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific in 1954. It was even bigger than expected, because something went wrong.

Planned as a five-megaton blast, it turned out to be 15 megatons, vaporizing three coral islands. A massive plume of smoke rose to 100,000 feet and drifted with the wind eastward, contaminating some 7,000 square miles.

By comparison, the “Little Boy” bomb dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, was equivalent to only about 15 kilotons of TNT.

Seven years after America’s Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb, the Soviets detonated the most powerful bomb of all time — the “Tsar Bomba” with a yield of 50 megatons of TNT — 3,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb.

On Oct. 30, 1961, Maj. Andrei Durnovtsev, a Soviet air force pilot, dropped the monster hydrogen bomb from his Tu-95 Bear bomber on boomerang-shaped Severny Island off the north coast of Russia.

According to a report by The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), established in 1996, “Tsar Bomba caused extensive environmental damage: the ground surface of the island was completely leveled, as were the rocks. Everything in the area was melted and blown away.”

Tsar Bomba could have been bigger. It was made to be 100 megatons of power if it were to have included a U-238 tamper — a neutron reflector that makes an atomic bomb explosion more efficient.

This capability was never demonstrated by the Soviets because they built only one Tsar Bomba.

But man’s explosions can’t compete with those made by nature.

NASA’s Richard B. Stothers in “The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath” claimed that the volcanic eruption on Sumbawa Island in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) was the largest observed eruption in recorded history.

It happened on April 10, 1815.

In The Smithsonian, Robert Evans said the blast sent “12 cubic miles of gases, dust and rock into the atmosphere over the island of Sumbawa and the surrounding area.

“Rivers of incandescent ash poured down the mountain’s flanks and burned grasslands and forests. The ground shook, sending tsunamis racing across the Java Sea. An estimated 10,000 of the island’s inhabitants died instantly.”

Ash pollution in the air worldwide lowered temperatures and caused crops to fail. The following year was called “The Year Without a Summer.”

Even skies in J.M.W. Turner paintings of that time were colored like the yellowish and reddish atmosphere.

In Lebanon, N.Y., Nicholas Bennet wrote that as late as May, “all was froze” and the hills were “barren like winter,” noting that temperatures dropped to below freezing almost all of May, and by July everything stopped growing.

A Norfolk, Va., newspaper reported that “The cold as well as the drought has nipt the buds of hope.”

Historian Curtis P. Nettels wrote in “The Emergence of a National Economy” that farm families who were wiped out by the event left New England for western New York and the Northwest Territory, hoping for a better climate, richer soil and better growing conditions.

It was nature-made climate change, creating three years of worldwide misery.

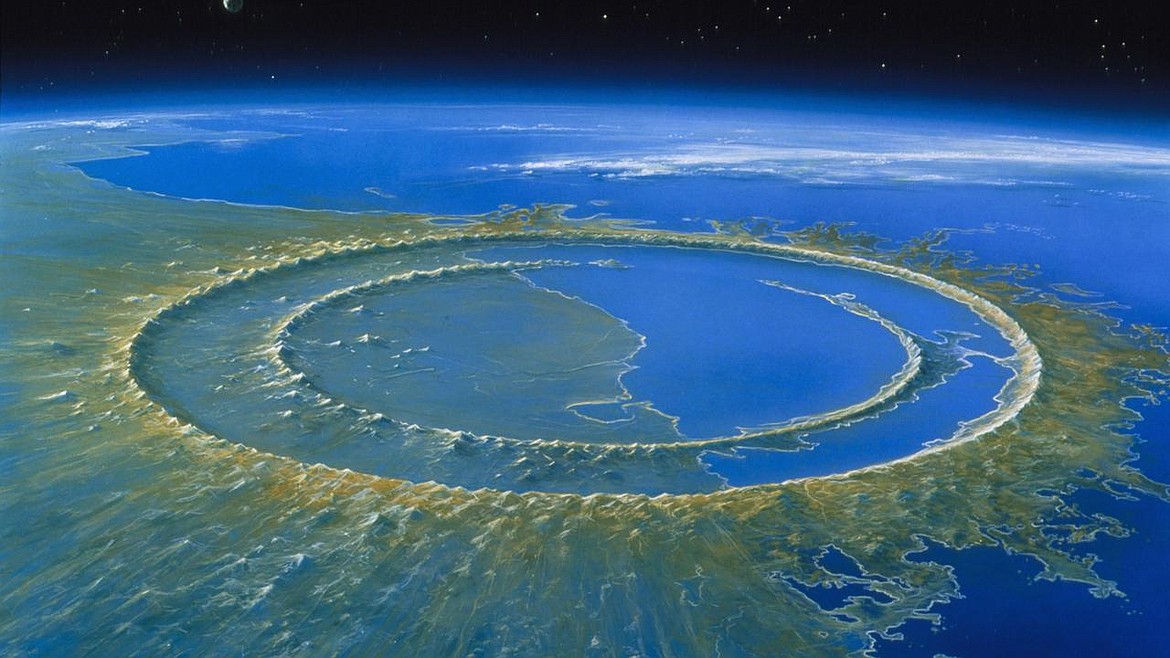

Scholars are still debating about what was the greatest explosion ever on Earth, with several theories debated. One possibility is Mexico’s Chicxulub.

According to scientists a huge asteroid or meteor flashed through the sky at 40,000 mph and hit Earth on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico at a place called Chicxulub causing a catastrophic explosion and crater 110 miles wide that supposedly wiped out the dinosaurs around the world.

National Geographic’s Chung-tat Cheung explains more:

“Sixty-five million years ago,” according to evolutionary scientists, “the last of the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct. So too did the giant mosasaurs and plesiosaurs in the seas and the pterosaurs in the skies. Plankton, the base of the ocean food chain, took a hard hit. Many families of brachiopods and sea sponges disappeared. The remaining hard-shelled ammonites vanished. Shark diversity shriveled. Most vegetation withered. In all, more than half of the world’s species were obliterated.”

Cheung wrote that it “would have choked the skies with debris that starved the Earth of the sun’s energy, throwing a wrench in photosynthesis and sending destruction up and down the food chain.

“Once the dust settled, greenhouse gases locked in the atmosphere would have caused the temperature to soar, a swift climate swing to topple much of the life that survived the prolonged darkness.”

Planetary science lecturer Gareth Collins of Imperial College London said if you were near enough to see it, you were dead.

Some scientists say that even volcanic explosions could have produced similar catastrophic results.

Seismologist Rick Aster at Colorado State University and former president of the Seismological Society of America says, “A seismic event of this size would be the equivalent of all the world’s earthquakes for the past 160 years going off simultaneously.”

Such is the power of nature.

- • •

Contact Syd Albright at silverflix@roadrunner.com.

- • •

Tsar Bomba devastation…

“Although the Tsar Bomba was detonated 4 kilometres above ground, a seismic shock wave equivalent to an earthquake of over 5.0 on the Richter Scale was measured around the world. The mushroom cloud reached a height of 60 kilometres. Third degree burns were possible at a distance of hundreds of kilometres.”

— CTBTO

Mount St. Helens and Tambora…

The 1815 eruption of Tambora…ejected about 30 to 80 times more ash than did Mount St. Helens in 1980… But even the Tambora eruption pales by comparison with the gigantic pyroclastic eruptions from volcanic systems such as Long Valley Caldera (California), Valles Caldera (New Mexico), and Yellowstone Caldera (Wyoming) — which, within about the last million years, produced ejecta volumes as much as 100 times greater.

— U.S. Geologic Survey

Bikini Atoll residents compensated…

The U.S. Government promised Bikini Atoll’s natives they’d be able to return home after the nuclear tests. Most were moved to the Rongerik Atoll and later Kili Island. Neither was suitable.

Bikini Island is currently visited by a few scientists and inhabited by four to six caretakers.

The government has paid the islanders and their descendants $125 million in compensation for damages and displacement from their home island.

Was A-bomb attack on Japan justified?

“Seven-in-ten Americans ages 65 and older say the use of atomic weapons was justified, but only 47% of 18- to 29-year-olds agree. There is a similar partisan divide: 74% of Republicans but only 52% of Democrats see the use of nuclear weapons at the end of World War II as warranted.”

— Pew Research Institute

The day the asteroid hit…

“The peak ring formed in a matter of minutes. Just after the impact, deep granite bedrock, flowing like a liquid, rebounded into a central tower as tall as 10 kilometers before collapsing into the circular ridge. Next, the peak ring was covered by a layer of jumbled-up rocks, called a breccia that contains chunks of blasted-up rock and impact melt.

“Then, in the hours that followed, ocean tsunamis dumped huge amounts of sandy sediment in the giant hole in Earth. Further deposition would come slowly, as life returned to the seas, and layers of limestone were built up in the ensuing millions of years.”

— Eric Hand, Science Magazine report about Chicxulub