A FATHER'S FIGHT Part Two: A Family Shattered

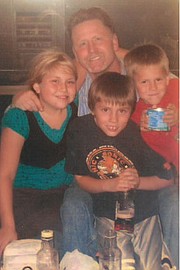

In the beginning, more than a decade ago, there was just Doug Bressie, a single dad who owned a Post Falls plumbing business as he raised three children between Post Falls and the family retreat — a log cabin near the small logging town of Emida, 30 miles south of St. Maries. He was in the process of building a house there, with a valley view, not far from Sanders Road.

The family resided, for the most part, in Post Falls on acreage above the Spokane River while expanding Bressie’s burgeoning plumbing business, traveling back and forth to Emida, where the family now lives.

“We had a perfect life,” Oscar Bressie, now 17, recalls. “We had horses, we lived outside of town. We rode dirt bikes. I don’t know why they (child protective services) wanted to ruin that.”

The gravel road below the Bressie’s Emida homestead is a dusty cloud in summer, as it heads west toward Tensed. Nearby State Highway 6 scales Harvard Hill, a winding strip of pavement that climbs in elevation through pine, fir and tamarack forests before plummeting southwest toward the Palouse prairie. Near the edge of a meadow where elk graze in spring is a former CCC camp, hidden and overgrown. Deer and turkey come here to nibble new grass and surrounding mountains press into a blue sky as if they were hammered on an anvil.

The family was spending a considerable amount of time at the Emida “hunting cabin,” as they called it, in 2008 when 11-year-old Dusty was stricken with a viral infection.

Bressie, who had meticulously and expertly tended to his daughter’s diabetes for years, according to court records, realized the infection could adversely affect her diabetes. To play it safe, he loaded the children into his pickup and they headed to St. Maries. Because there were no endocrinologists available, doctors shipped the 11-year-old girl to Spokane’s Sacred Heart Medical Center.

Nothing would be the same from here out.

At the hospital, as personnel tended to Dusty over a three-day period, and questioned Bressie about dosage and his routine of care, Stacy White, a representative of Idaho’s Child Protective Services who Bressie had dealt with before, appeared, Bressie recalls.

“I was horrified,” Bressie wrote in an affidavit. “White absolutely gloated when she walked into the room. I remember thinking … she must be enjoying herself.”

Previously, after an incident at school, White had accused Bressie of spanking Oscar, who was then 7. She made the boy pull down his pants as she photographed his buttock, without his father’s consent.

The case never gained traction because White’s photos were lost, but not before Bressie confronted White and her agency about it.

“I was upset my children were spoken to without my knowledge,” Bressie wrote, in an affidavit. “I was angrier when I found out photographs were taken of my son’s naked body by a stranger… This was highly inappropriate.”

At the hospital, his ability to care for his daughter’s diabetes was questioned.

“I told them they were making a mistake,” Bressie said. “I can do those calculations in my sleep.”

After some discussion, White, whose authority over Dusty, Oscar and Derringer, who was 6 at the time, now superseded Bressie’s, ordered that the children be taken into protective custody. Bressie was to leave them to the state, and he was escorted from the building.

White, who is now the regional supervisor of child protective services for the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare’s Panhandle district, declined comment for this article.

“It happened so fast,” Bressie said. “They kept saying stuff to keep the kids … stuff that never happened ... they kicked me out of the hospital … the police took me to the elevator and escorted me out … I was in shock.”

He tried returning for his children but was barred from entry.

He hadn’t even said goodbye, or been given an opportunity to assure his children that things would be OK.

“I walked in circles around the hospital,” he recalls. “They told me my care was inadequate.”

He sat on a park bench, speechless.

“I couldn’t drive,” he said. “I was mentally gone.”

James Hannon, a Coeur d’Alene attorney, met Bressie years later, after the worries of losing his children for good had made him lean, lightened the color of his hair and set lines on his already weathered skin.

“He was just a real solid guy,” Hannon said. “He hadn’t given up the fight.”

Bressie had already been through more than a half-dozen attorneys, including a host of overworked public defenders and many lawyers who he paid by traveling to jobs in North Dakota, taking out loans against his property, settling a workman’s compensation claim for a job-related knee injury, and by relying on the generosity of others.

Bressie came to Hannon for advice.

“God only knows how he held on for so long, and at what cost,” Hannon said. “Most other people would have thrown in the towel a long time ago.”

By then, a First District magistrate had ruled against the state’s handling of the situation and referred to the case as regrettable.

“If I had to describe this case in one word,” said Magistrate Judge Robert Burton in a 2012 ruling, “I would describe it as tragic. And the reason I say that is, because this case has gone on for so long.”

For several years, at the behest of the state, Bressie endured endless urinalysis tests, although no one had ever shown that Bressie had a drug or alcohol problem, the judge noted. There were an inordinate number of counseling sessions that included child care, diabetes management, business and personal finance classes, although no one ever showed that he was in need of any of those, the judge said. Child protective services pushed for his enrollment in psychosexual evaluation sessions based on an erroneous claim of sexual abuse after White learned Bressie had kept Dusty in his bed to monitor her diabetes during the night when she sometimes had seizures. Having her close by at night — to feel when her body suddenly got rigid — was the only way the dad would know if there was trouble, Bressie told the caseworkers.

No charges were ever filed against Bressie.

“That was not even a finding,” Burton said. “It was alleged, but it was not found.”

Despite the state’s insistence that Bressie admit to wrongdoing, and using his denial as a trigger to terminate his parental rights, a court-appointed evaluator prevented Bressie from undergoing a psychosexual evaluation. Evaluator Tom Hearn argued an evaluation was baseless, although the state continued to insist upon it.

In an affidavit read by the judge, Bressie wrote, “Dusty has severe diabetes complicated by seizures. I was told she could die if immediate action was not taken, as soon as she began seizing. I kept Dusty in my bed so I could tell immediately if she was having a seizure … (Stacy) White could not comprehend that I feared for my daughter’s life. Instead she accused me of sexually abusing Dusty and surmised that must be the reason I had Dusty in my bed.”

White threatened Bressie with arrest if he failed to comply or admit to abusing his daughter, according to the affidavit.

The agency was doing things its own way, Bressie said. Hidden from the purview of others, behind sealed files, its representatives made decisions away from the scrutiny of the courts.

“I told them I would take a psychosexual test,” Bressie said. “Where do I sign up?”

Bressie asked to submit to a lie detector test to put to rest claims that he was abusive, or that he had something to hide, but his then-attorney, public defender Jed Nixon, cautioned against it.

Because there was no evidence, and no judge’s order, neither test was administered.

“You don’t take a psychosexual evaluation unless there is a conviction,” said April Linscott, a Hayden attorney hired by Bressie to file a lawsuit against Idaho Health and Welfare.

There was never a conviction, or evidence of wrongdoing.

His case was suspended in the heavy liquid of child protective services alchemy while his paid attorneys, one at a time, released him as he ran out of money. They were replaced by a series of public defenders, assigned briefly, before the case was passed on.

All the while, Bressie’s children were being raised, against their will, in foster homes, or institutions away from their father, as the state made claims later found to be erroneous.

Child protective service caseworkers set up roadblocks for father-children reunions, court records show.

“I hated my wanna-be home,” Dusty Bressie, who now attends college in North Dakota, said recently. “By the time I was 12, I wanted revenge. I wanted to be around my brothers, my father, my pets, my family. The thing I wanted most was my life (back). I went to bed every night not praying to God ... But begging (to be reunited).”

But it was too late. Magistrate Judge Penny Friedlander, after listening to testimony from the state at a December 2009 hearing in Coeur d’Alene — that did not include Bressie or his children, even though they asked to attend — opted to move to terminate the father’s rights.

The agency’s testimony, however, was shown to be flawed.

Caseworker Todd Neel told the court Bressie suffered from mental health issues, and that he was “not able to handle the case plan.” A judge later ruled the case plan was unreasonable, despite Bressie having complied with the bulk of its stipulations.

Buying into unconfirmed allegations by the state of Bressie’s abuse, Friedlander made the father’s denial a cornerstone of her decision to terminate his rights.

“There has been a lack of compliance,” Friedlander said. She cited allegations of a personality disorder that the state proffered. “(They) go hand-in-hand with (the father) denying any history of abuse.”

Psychiatrists who treated the children around the same time had asked for confirmation from Health and Welfare of charges of abuse by the father. The evidence was never turned over.

In a report that was not presented to the court, psychiatrist Alan S. Unis, of Kootenai Behavioral Health, encouraged reunification of Dusty Bressie with her dad, and noted “we continue to see … discrepant observations regarding the father’s competency for managing the patient in his home.”

Unis told caseworkers, before they recommended termination of parental rights, that the girl would be at a “much higher risk if reunification were not the plan.”