'Ghost Cedars' stand vigil

Haunting remnants of the 1910 Fires stand along the narrow and dusty Moon Pass Road, which winds between tiny Avery and Wallace.

A traveler can witness for themselves the force with which those catastrophic wildfires raged.

Numerous large dead cedar snags - known locally as the Ghost Cedars - stand in a wetlands area along the North Fork of the St. Joe River.

It's a graveyard for the cedar trees, which were 300 to 500 years old when they burned in August 1910.

Those fires affected many in North Idaho, Eastern Washington and western Montana.

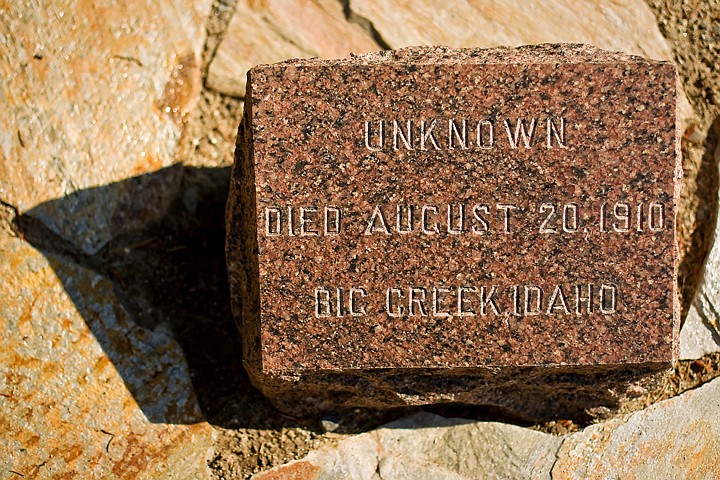

At least 85 people died in the fires that swept through the mountains of those states. Most of the dead were U.S. Forest Service firefighters. The final toll could have been as high as 130 dead.

Woodlawn Cemetery in St. Maries is the final resting place of nearly 60 firefighters, and many of them died Aug. 20 at Big Creek and Setser Creek.

Several communities and miles of railroad infrastructure were destroyed. Most of the destruction occurred in a firestorm on Aug. 20 and 21, often referred to as the "Big Blowup," which burned nearly three million acres of forest. Nationally, an estimated five million acres of national forest burned during the 1910 fire season. State, private, reservation, and other lands also burned.

A third of the booming city of Wallace was burned, and the towns of Mullan and Avery were barely spared. Avery had 250 people living there in 1910.

Today, the Ghost Cedars are grayish, some 6 to 7 feet in diameter at the base. Some rise, branchless, from massive bases to long fine spikes at the peak. Those broken near the base are blackened inside where the heart rot of the trees were scorched.

The river rushes and gurgles through the bottom wetlands where the cedars stand. Dense sedges and shrubs grow in muck near the stream. Moose bed down where they can find dry patches of ground.

There are several hundred of the Ghost Cedars stretching for about a mile along the river.

They aren't the only cedar snags still standing as remnants from those fires, but "this is the area where they're most visible and easy to find," said Jason Kirchner, a spokesman for the Idaho Panhandle National Forests.

If they weren't cedar they likely wouldn't be standing today.

Still, despite the strength of the wood, "There are less and less (standing) every year," he said.

It took thousands of years to grow the cedar forest, he said. A raised water table, gophers that like to eat young trees, and frost keep cedars from repopulating the valley bottom. The U.S. Forest Service tried to plant cedars, but they didn't survive, Kirchner said.

About eight species of trees grow on the hillsides above the valley bottom. The hillsides look much the same as they did in 1910, he said.

"That valley was a hub of activity, between logging, railroads, and mining," said Kirchner. "There were a lot more people in the woods back then, compared with today."

The Forest Service says that historically, in an average summer, the river bottom wetlands are too moist to carry a forest fire - even if the surrounding hillsides are dry enough to burn.

But in 1910, the old cedars in this bottom did burn. The severity of the drought and the heat conditions that year made it possible.

A fire of the magnitude of the Big Blowup burns everything in its path with great intensity, the Forest Service says. There was nothing fire-resistant that summer.

Living cedar stands might one day take root again in this valley bottom, Kirchner said.

"But not in our lifetime," he said.