For love of the lake

COEUR d'ALENE — From the deck of his Boothe Park home, Skip Murphy has a view of his handiwork and his family's fingerprints across the waves and along the shorelines of Lake Coeur d'Alene.

"One of the reasons why I bought this house is I can sit here and see almost all the things that I built,” he said Monday afternoon. “There’s Arrow Point, Gozzer Ranch, the Panhandle Yacht Club."

Murphy, 77, retired last month from his role as the owner of Murphy Marine Construction Inc.

The Murphy family's local influence stretches back to the 1890s when Skip's grandfather, Loren J. Murphy, first arrived in North Idaho and worked as a steamboat captain on Lake Coeur d'Alene.

Skip's late father, Fred Murphy, was a legendary tugboat captain who was well-loved by business partners and community members alike.

“My son (Shaughn Murphy), he’d be the fourth generation of us here," Skip said. "He’s working in the business, too."

Upon his retirement, Skip sold Murphy Marine to the Hagadone Marine Group, for which he will serve in an advisory role for at least the next three years. Shaughn has assumed a lead role with Hagadone Marine and Skip's son-in-law, Mike Jensen, and the Murphy crew will retain dock-building positions within the company.

The Murphys have long had working relationships with Hagadone properties, especially Hagadone Marine.

“I can’t think of anybody else that would do it any better,” Skip said.

In the 1980s, Murphy Marine was commissioned to build The Coeur d'Alene Resort Boardwalk Marina, a crowning achievement for both companies and the Lake City. Skip and his late brother, Loren Murphy, conducted the lion's share of work on the 3,300-foot-long wooden wonder that would come to be known as the world's longest floating boardwalk.

“Dad was fully retired at the time we built that,” Skip said. “My brother and I built that marina.”

The winter of 1984-85, when the boardwalk was constructed, was a harsh one.

“It was built in what I consider one of the worst winters we’ve had in 100 years. It was awful," Skip said. "The lake froze over early and thawed out late. Of course, we had a time restraint. They wanted it done at a certain time for opening.”

Seven-day workweeks and long hours were spent crafting one of Coeur d'Alene's most iconic landmarks.

“We’d get up in the dark and go to work, and come home in the dark,” Skip said. "Never home in the daylight.”

Construction took place at the Murphy Construction yard at Casco Bay. All the materials showed up in Coeur d’Alene, so Skip and his crew dumped logs in at Third Street and made them into bundles to tow along channels from The Resort to the shop. Assembled pieces were floated back across the lake.

This could only happen after tugboats cleared paths through the frozen surface.

“You could see the ice around everything,” Skip said. "You had to chip ice out just to move a log. Every morning we’d get out the tugboats and break up all the ice we could and try to wash it out of there. It was nasty.”

And not without incident.

“Every once in a while, somebody’d fall in, and we’d have to dig him out and take him in by the stove and thaw him out," Skip said.

Workers weren't the only people the Murphys rescued over the years. One winter, Skip saved the day for a group of youngsters who unintentionally found themselves on an ice floe.

“The kids were out playing hooky or something. They got out on the lake on a big cake of ice, and it broke loose and was drifting up the lake with these kids on it,” Skip said. “I saw them from Casco Bay, so I hopped in the tugboat and went out there and scooped them up, took them to shore and dropped them off with the rescue guys that were pacing around on the beach out there.”

When he looks at the boardwalk and thinks of how much his family has contributed to Coeur d'Alene, he’s “proud as can be,” he said.

He said his dad would be going crazy to see all the changes that are happening locally.

“He wasn’t really into large development, that sort of thing. He liked the lake the way it was,” Skip said. “I’m kind of that way too, but you can’t fight it. You’ve got to be able to work along with it."

Skip was only 8 when he started working on boats with his dad.

"I could run the tugboats and do all that stuff," he said. "I just never found any way to step off. This is what life was.”

He recalled going on two-week summer adventures aboard his dad's marine pile driver.

“It had enough room in the back that you could put bunks in it," he said.

His dad would load up about 60 pilings on the pile driver and sell them to people who flagged them down.

"I like all the people on the lake. That’s where Dad came in. He was a real people person," Skip said. "He loved people and he’d stop and talk with them. When he was up the lake driving pilings, the last job, you tie up the rig there and sleep there that night, and they’d usually have a big beach party or something while the circus was in town, so to speak.

“We’d go up one side of the lake and down the other, and just lived on the boat while we were doing it,” he said. “I wouldn’t trade a minute of my life here."

Skip said Craig Brosenne, president of Hagadone Marine Group, had the right idea to buy him out when he did.

“I thought it was about time, because I’m 77 years old, and never taken hardly a vacation,” Skip said. “I thought, 'This is a good time to retire.’ So I retired."

Brosenne said Murphy Marine has been a cornerstone of the marine industry on Lake Coeur d’Alene for decades. He said Skip and his wife, Sue, have built an incredible legacy.

"Our relationship with them has always been one of mutual respect and collaboration," Brosenne said.

He said Skip Murphy's expertise and dedication have been invaluable to the growth of the industry, and his contributions have left an indelible mark.

"As we move forward, we are committed to honoring and continuing the exceptional legacy that Skip has established," Brosenne said. "We are delighted to share that Skip will continue to play a crucial role as counsel during this transition, ensuring that the values and standards he set will remain at the heart of Murphy Marine."

Hagadone Marine's acquisition of Murphy Marine was not just a business move, Brosenne said.

"It is a testament to the deep, enduring relationship between Hagadone Marine Group and the Murphys," he said. "We look forward to building on the strong foundation Skip and Sue have laid and to continuing to serve our community with the same passion and excellence."

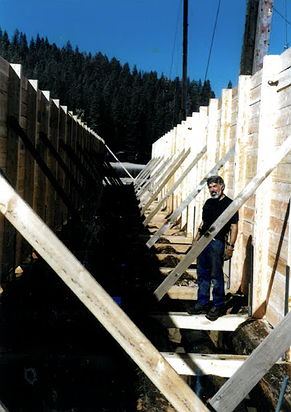

Skip Murphy's late brother Loren Murphy is seen with pieces of The Coeur d'Alene Resort Boardwalk Marina, which he and his brother constructed in the mid-1980s. “It’s upside down right now,” Skip said, pointing to the photo. "We built them upside down and then you flipped them over because you couldn’t do any of this work underwater.”

Skip Murphy's late brother Loren Murphy is seen with pieces of The Coeur d'Alene Resort Boardwalk Marina, which he and his brother constructed in the mid-1980s. “It’s upside down right now,” Skip said, pointing to the photo. "We built them upside down and then you flipped them over because you couldn’t do any of this work underwater.”